3 Historic Battles That Shaped Minnesota

The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 was a pivotal moment in Minnesota, beginning in August when disputes over land, resources, and broken treaties escalated into armed conflict. Across the Minnesota River Valley, battles at New Ulm, Birch Coulee, and Wood Lake involved Dakota warriors defending their homelands and settlers striving to protect their communities. These engagements brought significant loss of life, widespread destruction, and lasting changes for both Dakota people and Minnesota settlers. Today, preserved battlefields and historic markers honor the events 1862, leaving a lasting mark on the state.

Battle Of New Ulm

Members of the New Ulm Battery firing a salute in New Ulm, Minnesota. The battery was formed as a defense measure in 1863 after the Great Sioux Uprising destroyed part of the town in 1862. The unit, with a full membership of 42, has never had to fire in defense. It uses the cannons for salutes on Memorial Day and the Fourth of July. The uniforms were copied from that of a Civil War officer who returned home in time for the Indian battle and became the first battery commander. Photo via WikimediaCommons

The Battle of New Ulm unfolded in August 1862, as Dakota warriors clashed with local settlers and a hastily assembled militia. On the 19th, a small Dakota force attacked the town, killing five settlers. Judge Charles Flandrau of St. Peter was chosen as military commander, and the arrival of refugees increased New Ulm’s population to nearly 2,000, though only about 300 men were armed and ready to defend the town.

A few days later, more than 600 Dakota under Chief Wamditanka (or Wambditanka), also known as Big Eagle, Wabaṡa, and Makato, launched a larger assault. Defenders held a three-block perimeter, and heavy fighting damaged much of the town. A sudden thunderstorm helped limit fires during the attack, preventing further destruction.

By Aug. 25, Flandrau ordered the evacuation of about 2,000 residents to nearby towns, including Mankato, St. Peter, and St. Paul. Many homes and farms around New Ulm were destroyed, and the approximately 45 civilians killed during the attacks were buried in the New Ulm City Cemetery.

Today, monuments in New Ulm, including the Defenders’ Monument, commemorate the events 1862. Erected by the State of Minnesota in 1891, the monument honors the residents who defended the town during the war.

Battle Of Birch Coulee

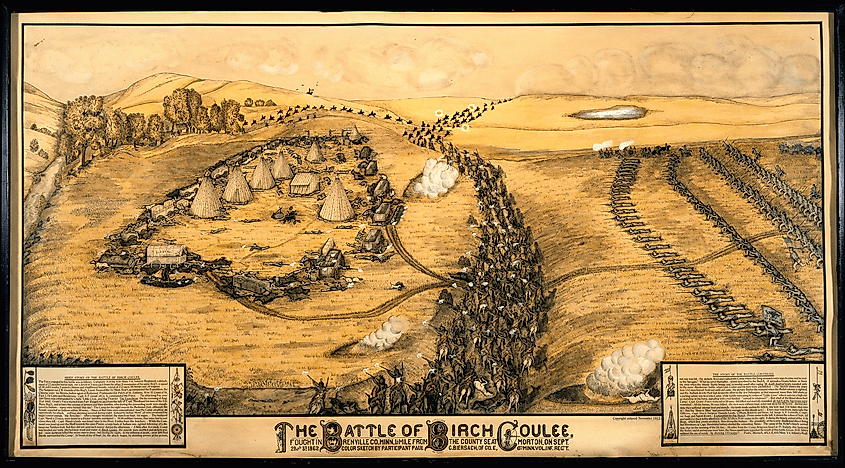

Lithograph depicting the Battle of Birch Coulee. Photo via WikimediaCommons

The Battle of Birch Coulee, also part of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, unfolded near present-day Morton, when Dakota fighters launched a surprise attack on a camp of Minnesota state troops and civilians.

On Sept. 1, Maj. Joseph R. Brown led about 170 men from Fort Ridgely on a mission to bury settlers killed in earlier fighting. That evening, his detail camped in an exposed spot near Birch Coulee Creek. Before dawn on Sept. 2, about 200 Dakota warriors, led by chiefs Gray Bird, Mankato, Red Legs, and Big Eagle, launched a dawn ambush, beginning a 36-hour siege. Although Big Eagle had reservations about going to war, he felt compelled to stand with his band and his people. Scouts had tracked Brown’s expedition and confirmed its location, allowing Big Eagle’s men to move into position west of the camp, about 200 yards behind a knoll.

Pinned down without water and surrounded, the U.S. soldiers dug shallow rifle pits and even used the bodies of fallen horses for cover. By the time Col. Henry Sibley arrived with reinforcements on the morning of Sept. 3, 13 men and 90 horses lay dead, with more than 50 others wounded. Dakota losses were reported as very few. The clash at Birch Coulee was the deadliest defeat for U.S. troops during the war and a significant victory for the Dakota.

After the war, Big Eagle surrendered to Sibley at Camp Release. He was tried by a military commission and sentenced to death, but because there was no evidence that he had committed any specific murders, his sentence was commuted. He served for a few years before President Abraham Lincoln approved his release in 1864.

Today, the Birch Coulee Battlefield State Historic Site, managed by the Renville County Historical Society, preserves the grounds with trails, markers, and restored prairie. Visitors can follow a self-guided path through the landscape, where interpretive signs share accounts from both sides, including U.S. Army Capt. Joseph Anderson and Big Eagle.

Battle Of Wood Lake

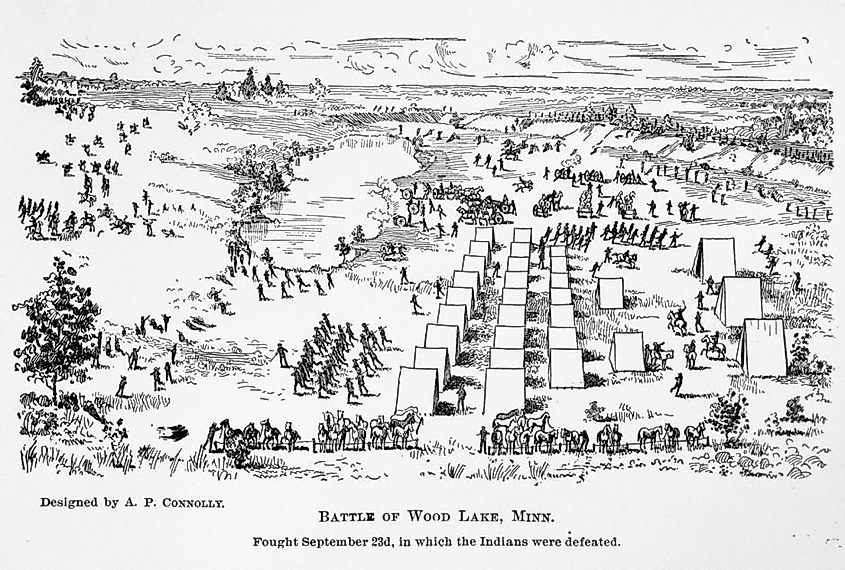

Following the Battle of Birch Coulee, Col. Henry Sibley pursued Dakota forces across southwestern Minnesota. On Sept. 23, his troops, camped near Lone Tree Lake, were ambushed when Dakota warriors opened fire on a group of soldiers who had gone foraging. The skirmish escalated into the Battle of Wood Lake.

Sibley’s militia, including veterans of the Third Minnesota, repelled the Dakota attackers. Seven U.S. soldiers were killed and more than 30 were wounded, while several Dakota were killed during or immediately after the battle.

Following the battle, some Dakota surrendered, while others moved west. The U.S. victory was followed by the trial and execution of 38 Dakota men in Mankato and the relocation of most Dakota people from Minnesota.

During the battle, Little Crow (Taoyateduta), the principal leader of the Dakota during the war, and his commanders considered three strategies: a nighttime attack, an early-morning assault on the troops’ camp, or attacking the column as it marched to divide it. The Dakota chose the column ambush, but foraging soldiers unexpectedly encountered them, and the element of surprise was lost.

The Wood Lake Battle Site, near Montevideo, marks where the last major fighting of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 took place. Today, the Wood Lake Battlefield Preservation Association cares for the grounds, restoring parts of the landscape to how it looked in 1862 and adding interpretive signs. Visitors can walk the site, learn the history, and reflect on the lives lost on both sides of the conflict.

Today, the sites of the U.S.-Dakota War’s major battles are preserved as historical landmarks. The Defenders’ Monument in New Ulm, the Birch Coulee Battlefield State Historic Site, and the Wood Lake Battle Site allow visitors to explore the landscapes where these events unfolded. Interpretive signs, restored terrain, and historical markers provide context for the actions, outcomes, and individuals involved in 1862, ensuring that the stories and experiences of both settlers and Dakota warriors remain accessible to future generations.