8 Famous Historical Events That Never Really Happened

It has been said that history is written by the victors. The stories below seem to prove that is often the case. Because history is often shaped by the goals of those who record it, many examples of important historical events do not reflect the full truth of what happened. In extreme cases, though, the truth is so far from the popular story that uncovering it changes everything the story stands for. As the examples discussed below show, there are many famous events that everyone believes to be true that just aren't. From sinking ships and famous first flights to ongoing celebrations like Columbus Day and Thanksgiving, here are some famous historical events that didn't actually even occur.

The Titanic Didn't Sink Just Because It Hit An Iceberg

Fans of the movie Titanic will be surprised to learn that the luxury ocean-liner wasn't actually brought down just by hitting an iceberg but by a massive coal fire that staff had been told to keep secret from the passengers. A re-examination of available evidence suggests that the fire had been burning for more than a week before the ship left Southampton, England, and the damage could actually be seen from the outside. Experts estimate that the fire was hot enough to have reduced the strength of the hull up to 75 percent by the time the ship contacted the iceberg. Even worse, the fire was so bad that even if the ship hadn't collided with an iceberg, the fire would have caused a series of catastrophic explosions well before it ever reached its destination in New York.

Lady Godiva Never Rode A Horse Naked Through Town

The popular and visually striking story of a woman's naked horseback ride through a town to protest against crippling taxes has no basis in history. There was a rich woman around whom the tale was built, but her name wasn't Godiva; she was never referred to as a lady, and she certainly never took that ride. In reality, her name was Godifu, and she lived in 11th-century Coventry, England. She was never called "Lady" because, at that time, the term could only be used to refer to the Queen.

Also, Coventry was a tiny farming community with no streets or marketplace for her to ride through. It was, in fact, too small to have been subjected to taxes at all. Even more telling, there's no mention of this infamous act at all until many years later, when the story appeared in the work of a monk at the Abbey of St. Albans.

But that's not to say that Godifu isn't a woman worth celebrating, which is maybe why she became the heroine of her own tall tale. She and her husband founded a Benedictine monastery to which she gifted treasures made from her own melted-down gold and silver jewelry. When she died, she gave the monks a valuable gem and gold chain to adorn the statue of the Virgin Mary.

And it seemed the monks did venerate their patroness. When a stained glass window from her monastery at Coventry was restored, it showed an image of a woman with long blonde hair. The image doesn't seem to be of an angel or saint, so it may well be that Godifu's appearance is something that the tale of Godiva's ride got right.

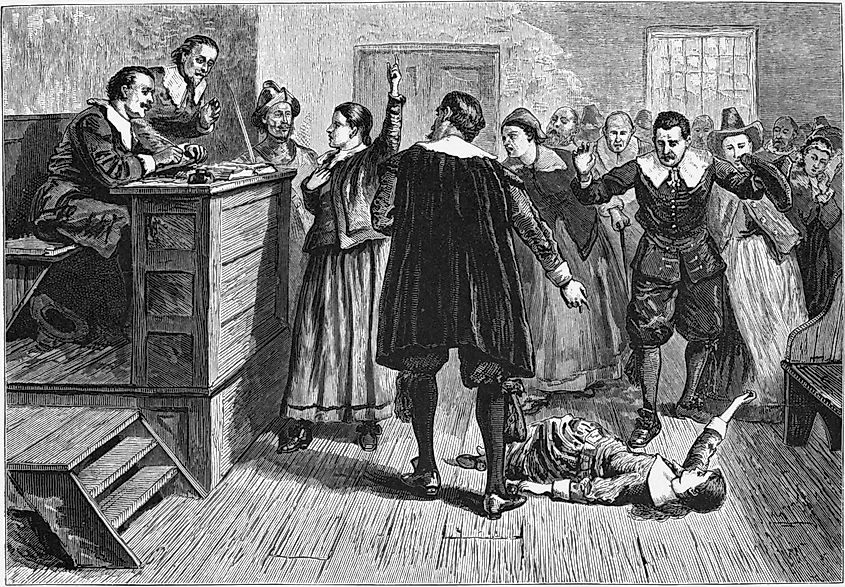

There Were No Witch Burnings In Salem

Though the 1692 witch trials in Salem were unfortunately very real, the idea that the accused were burned at the stake is not. In fact, there is not a single case of a suspected witch burned at the stake at that time. Instead, out of almost 200 people who were accused in the panic, 19 were found guilty and hanged, in keeping with practices from England. The idea of burning witches comes from centuries earlier and elsewhere, mainly in the 15th through 18th centuries in Western Europe. But there seems to have been something about that image that is seared into society's collective memory because it remains intimately tied to the fate of accused witches.

Charles Lindberg Was Not The First To Fly Across The Atlantic

Charles Lindberg was far from being the first to fly non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean. He was actually the 67th! Credit where credit is due, though, he was the first to do it all by himself, in the air for 33.5 hours from Roosevelt Field and landing in Paris, France, in May of 1927. But well before him were Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown, who flew for 16 hours from St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada, to a bumpy landing in marshland near Clifden, County Galway, Ireland, in terrible and dangerous conditions in June of 1919.

In a flight full of mishaps, they rushed their take-off and almost didn't make it over the trees near the runway, suffered a failed radio, and fog and clouds that foiled their navigation. To get to clear skies, they flew up into freezing temperatures and had to clear snow and ice from the sensors outside the cockpit repeatedly. After hours of trying to stay awake with coffee, whiskey, and singing, the aircraft stalled, the exhaust pipe blew, and the generator failed. They decided their only chance was to descend enough for the plane to thaw. It worked, and they saw Ireland beneath them. Their landing damaged the plane as what they thought was a field was actually marshland. In all, perhaps the true achievement is that they survived such an ordeal at all. The other 64 people who crossed the Atlantic before Lindberg were passengers in two separate dirigibles, one carrying 31 from Scotland to the US in 1919 and one carrying 33 from Germany to New Jersey in 1924.

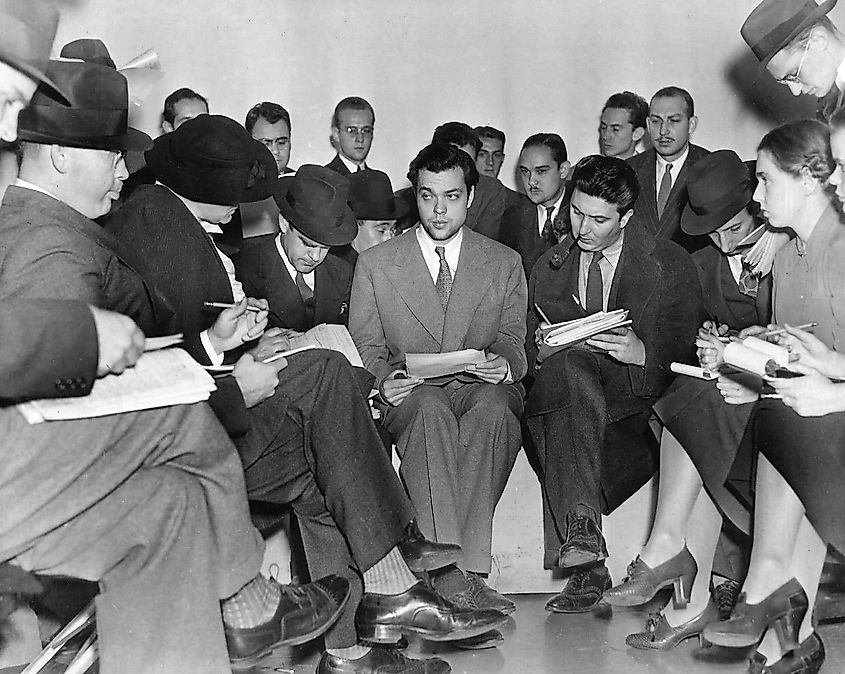

The "War Of The Worlds" Broadcast Did Not Cause Panic

It's a tale of two hoaxes at once: the fake news bulletin and the fake panic the papers reported it caused. In an attempt to discredit the then-new medium of radio, the newspapers of the time grossly exaggerated the reaction to Orson Welles' now-infamous Halloween night 1938 broadcast of War of the Worlds. It's a popular anecdote that the fictional alien invasion told through fake news bulletins was so realistic that mass panic broke out across the United States, leading to shock, suicide, violence, and death. In fact, the night it aired, there was little to nothing to be seen.

However, according to a telephone survey conducted that night, Only 2 percent of respondents seemed to have heard it, and no one said anything about being alarmed. But when newspapers began running the story of the panic the show caused, over the years, the tale grew, and more and more people claimed to have heard it and believed it.

Why would the newspapers do this? The growing popularity of radio had been damaging to newspaper revenue. An editor from the New York Daily News saw first-hand that no panic existed just as the War of the Worlds was ending, but published about the panic anyway. Ironically, by attempting to paint radio as untrustworthy, they themselves showed themselves to be deceptive and became their own cautionary tale of the power of media.

No One Jumped Out Of Windows When The Stock Market Crashed

Another panic that was greatly exaggerated was the reaction to the 1929 Wall Street stock market crash. Though it was no doubt a terrible day in history, with far-ranging effects in America and around the world, the widely-repeated story of brokers immediately jumping out of windows was not part of it. In fact, New York City's medical examiner made a point of saying that the suicide rate had actually been lower than in the previous year.

So, where did that all come from? Winston Churchill had a role to play. In America at the time, Churchill witnessed someone fall from the 16th floor of his hotel. He attributed this to the stock market crash, but it was actually the accidental death of a tourist, not an intentional act. It also occurred too early in the day to have been a reaction to the crash. It was no doubt also immortalized by a widely-published Will Rogers joke that, "When Wall Street took that tail spin, you had to stand in line to get a window to jump out of."

Columbus Didn't Discover America

Every fall, when Columbus Day rolls around in the United States, there is animated debate about the historical reality of who Columbus was and what he did. This would be the perfect time to chime in with the fact that Columbus did not, in fact, discover America. He never even laid eyes on what became known as the North American continent, landing in the Caribbean trying to get to China from Europe. Of course, even if he had, there had been people living all over the Western hemisphere for thousands of years.

Just to add insult to injury, the names many have been taught for his three ships are not true either. The Niña was just the nickname for a ship called the Santa Clara. As for the Pinta, it's a nickname from the Spanish for 'prostitute.' It's enough to make you wonder if we all have to go back to school.

The First Thanksgiving Was Not Harmonious

After Columbus Day, many Americans start preparing for Thanksgiving, a major holiday set aside as a time to share a meal with family and friends. Unfortunately, the touching story most people have been told of the first Thanksgiving at Plymouth, Massachusetts, is an invention meant to rewrite what was a violent and turbulent colonial process.

When the pilgrims arrived in Plymouth in 1620, the inhabitants of the area, mostly the Wampanoags, had already experienced 100 years of negative conflict with Europeans, including slave raids and epidemics. The truce they made was short-lived and was the beginning of 50 years of abuse and exploitation by the colonists, the ongoing spread of disease, and ended in a devastating war.

The story, as now told, was started in the late 1700s by pilgrim descendants who wanted to establish their lineage as the founders of America and justify the taking of land from the people already living there. This idea grew in popularity until the day of Thanksgiving was formalized in 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln to encourage unity during the Civil War.

In many cases, far from being just over-simplifications, the truth of many of these events is so far from the accepted story that they're simply inaccurate. By learning the truth about these pivotal times, we can begin to see society at present for how it really is and not how someone would wish it to be seen.