11 Of The Most Captivating Small Towns In Northern California

Map Northern California by senses, not freeways: the clang of a harbor bell above sea stacks, the sulfur trace of hot springs, and the hush inside a redwood grove.

This list gathers 11 places where Northern California stays legible at street scale: coast art colonies, fishing hamlets, wine plazas, Gold Rush holdouts, and railroad corners that never unlearned their purpose. Each town carries a single, unmistakable signature and together they sketch a working atlas of the region.

Mendocino

Mendocino doesn’t feel like it was built, it feels like it was placed. Perched on a coastal headland, this unincorporated village is the only town on the California coast designated as a historic landmark in its entirety. It began as a logging settlement in the 1850s, but what remains is a grid of weathered New England-style homes wrapped in salt air and fog, many built by shipwrights. The town’s compact blufftop layout offers immediate views of sea arches, jagged cliffs, and whales breaching offshore. Fewer than 1,000 people live here, but the town sustains a striking density of galleries, gardens, and performance venues.

The Mendocino Art Center, founded in 1959, is still the village’s cultural anchor, offering exhibits, workshops, and artist residencies year-round. Just south, the trails at Mendocino Headlands State Park begin at the edge of town and follow cliffs over pocket beaches and sea caves. Gallery Bookshop, a local institution, stocks coastal literature and features a resident cat named The Great Catsby. Across the street, Café Beaujolais, set in a restored 19th-century farmhouse, serves French-Californian cuisine using regional mushrooms and produce.

Trinidad

Trinidad sits on a forested bluff 200 feet above the Pacific, one of California’s smallest incorporated cities by population and square mileage. The town’s original Yurok name, Chuerewa, still appears on signage, and the current harbor is home to one of the last remaining commercial fishing piers in the state that operates without a marina. The coastline here is fragmented by offshore rocks protected under the California Coastal National Monument, which begins just yards from Main Street. On foggy days, the town’s memorial lighthouse fog bell is often the only sound heard above the tide.

Trinidad State Beach begins at the base of a narrow path below Edwards Street and opens to tidepools, giant driftwood, and views of Pewetole Island. Nearby, the Trinidad Museum, housed in a former craftsman bungalow, contains rotating exhibits on Yurok lifeways and the timber industry. Lunch is available a few minutes uphill at The Lighthouse Grill, where the mashed potato-stuffed "Humble Burger" has become a regional curiosity. Further south on Stagecoach Road, Sue-meg State Park (formerly Patrick’s Point) offers hiking trails to sea stacks, native plant gardens, and a reconstructed Yurok village.

Ferndale

Ferndale’s Main Street is a functioning architectural timeline. The town holds one of the highest concentrations of well-preserved Victorian storefronts in the western U.S., many built during the 1880s with profits from dairy and logging. Known locally as “Butterfat Palace Row,” these buildings now house bookstores, saloons, and antique shops, but their original detailing remains. The entire town is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Ferndale’s cemetery climbs a steep green hillside above town, offering panoramic views of the Eel River Valley from grave markers dating back to the Gold Rush.

On Main Street, the Ferndale Museum displays hand-cranked seismographs and a working telephone exchange once used during the 1964 flood. A block away, Mind’s Eye Manufactory hosts art installations and small-venue performances inside a converted Masonic temple. For lunch, Tuyas serves Oaxacan-inspired plates inside a restored storefront with original transom windows. Just outside town, Centerville Beach County Park extends for nearly nine uninterrupted miles, framed by cliffs and the Pacific.

Point Reyes Station

Point Reyes Station was built beside the San Andreas Fault, and it shows. The town’s former railway depot shifted 18 feet during the 1906 earthquake, a fact still marked on the Earthquake Trail nearby. This is not a coastal town, it’s an inland hub serving the surrounding dairies and wilderness, but its identity is shaped by tides, wind, and fog. It remains one of the few towns in California where organic farms, native tule marshes, and marine sanctuaries meet at a crossroads with one gas pump and no stoplights.

At the edge of town, Toby’s Feed Barn operates as a working feed store and public gallery, hosting installations, author talks, and the Sunday farmers market in the back lot. The Bovine Bakery opens by 7 a.m. and sells out of morning buns by 10. Around the corner, the Point Reyes Books inventory leans toward climate, land-use policy, and philosophy, often pairing book launches with field walks. Down Mesa Road, the Tomales Bay Trail offers a two-mile loop through pastures and coastal scrub, with tule elk sometimes visible on the ridgeline.

Occidental

Occidental was born from a railway junction and remains bordered by forest on all sides. Originally a logging stop on the North Pacific Coast Railroad, it evolved into a retreat for artists and off-grid builders in the 1960s. The town center spans just a few blocks, nestled tightly in a narrow valley of second-growth redwoods. The West County Trail runs through its eastern edge, tracing the former railbed used to ship lumber to the Marin coast.

Howard Station Café serves as a central landmark, operating out of a former 1930s roadhouse with egg-heavy breakfasts and a wide front porch. Down the street, Hand Goods displays textiles and ceramics made by local artists, many of whom live within walking distance. On Friday nights, Negri’s Original Italian Restaurant fills with multigenerational families seated at long tables for minestrone, chicken cacciatore, and spumoni. Just uphill, the Occidental Center for the Arts hosts chamber music and poetry readings in a former schoolhouse. Beyond town limits, the Grove of Old Trees preserve protects a rare stand of unlogged coast redwoods accessible by a narrow ridge road.

Calistoga

Calistoga sits at the foot of Mount Saint Helena, at the northernmost edge of the Napa Valley, where geothermal activity surfaces as hot springs, fumaroles, and volcanic ash. The town’s name stems from a 19th-century malapropism, “Calistoga of Sarafornia”, and it has preserved that accidental eccentricity. Unlike neighboring valley towns, Calistoga kept its low-key scale and still prohibits big box stores and fast food. The ground here steams. The sidewalks smell faintly of sulfur.

Dr. Wilkinson’s Backyard Resort & Mineral Springs offers access to the town’s signature mud baths, originally promoted in the 1950s and still made with local volcanic ash. Down Lincoln Avenue, Café Sarafornia serves corned beef hash and black coffee beneath a sign that hasn’t changed in decades. Just west of town, the Old Faithful Geyser of California erupts roughly every 15 minutes, with on-site goats and picnic grounds. The Sharpsteen Museum,on Washington St., contains scale dioramas of 1860s Calistoga and exhibits on its founder, Sam Brannan. Between these landmarks are family-run tasting rooms, bike rentals, and produce stands operating from coolers and honor boxes.

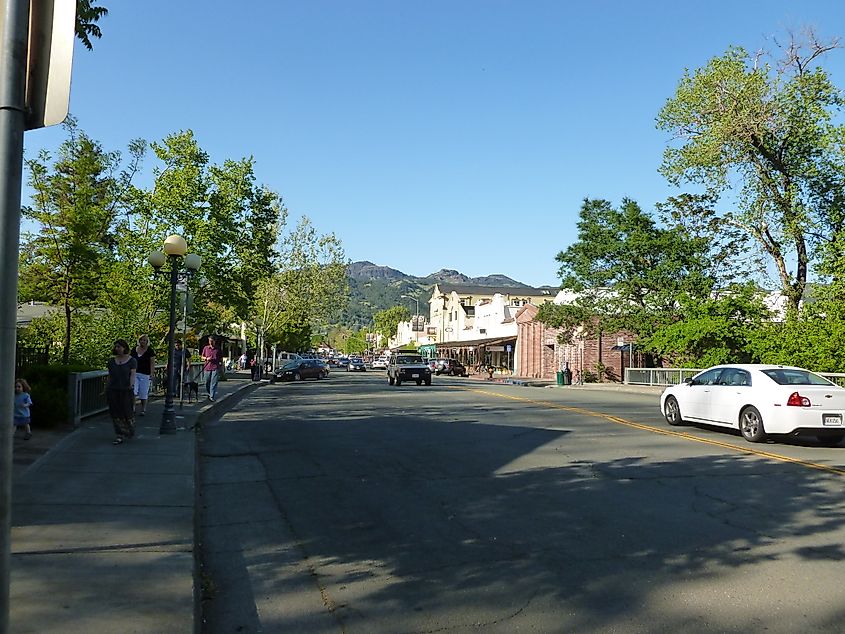

Healdsburg

Healdsburg occupies a former Pomo village site where three wine-growing valleys converge: Dry Creek, Alexander, and Russian River. The town developed around a 19th-century plaza, which remains its core. Unlike other wine country towns, Healdsburg never lost its agricultural infrastructure, it simply repurposed it. Old grain silos are now part of hotel courtyards, and former gas stations serve as tasting rooms. It’s one of the few towns in Sonoma County where a vineyard begins within walking distance of the post office.

The Healdsburg Museum, housed in a former Carnegie library, contains archives of the town’s boom-and-bust history tied to hops, prunes, and rail. Just off the plaza, Flying Goat Coffee roasts on-site and operates with a no-wifi policy that keeps the focus on counter service. Nearby, the Little Saint building, originally a modernist café and market space, has reopened under various pop-up concepts but remains a draw for its minimalist steel-and-glass design. For outdoor access, the Healdsburg Ridge Open Space Preserve includes oak woodlands and serpentine meadows, with intermittent views of Fitch Mountain.

Nevada City

Nevada City holds one of the best-preserved Gold Rush-era downtowns in California, but what defines it is its second act. After the collapse of hydraulic mining in the late 1800s, the town faded, then resurfaced in the 1960s as a countercultural enclave. Its Victorian buildings were restored not by preservationists, but by newcomers who turned livery stables into performance spaces and general stores into galleries. Today, the town’s economic engine runs on small-batch publishing, music festivals, and low-impact tourism shaped by its elevation, density, and access to the Yuba River.

The Nevada Theatre, operating since 1865, still hosts film screenings, stage plays, and concerts under pressed tin ceilings. The Firehouse No. 1 Museum contains artifacts from both the town’s mining history and the Wopumnes tribe, whose ancestral lands surround the region. South of Broad Street, Pioneer Park offers shaded picnic areas and summer concerts within walking distance of downtown. In warmer months, locals swim at the Yuba River’s Hoyt’s Crossing or hike to the rock outcrops above Edwards Crossing.

Murphys

Murphys was once known as the “Queen of the Sierra” and functioned as a key supply stop during the 1849 Gold Rush. More than $20 million in gold passed through its creekside claims before the veins dried up. Unlike other mining towns, Murphys didn’t collapse; it transitioned into a ranching and orchard economy, and later became one of the earliest Central Sierra wine hubs. Vineyards now surround the townsite, but the original grid, built in the 1850s, still structures the rhythm of Main Street.

The Murphys Historic Hotel, opened in 1856, still operates with a logbook that includes Mark Twain and Ulysses S. Grant. Just up the street, Alchemy Café serves local wine flights alongside dishes like mushroom pot pie and bison meatloaf. For a slower pace, the Murphys Community Park borders Angels Creek and includes shaded picnic tables, a bandstand, and a narrow footbridge crossing to the residential side of town. At the far end of Main Street, Ironstone Vineyards maintains a wine cavern, museum, and amphitheater, where touring acts perform beside mining relics and a 44-pound gold nugget.

Truckee

Truckee began as a railroad town at 5,817 feet, the first major stop east of the Sierra crest, where engines cooled and emigrants crossed into California. The town's name comes from a Paiute chief who greeted settlers with “Tro-kay!”, a word of welcome. Its main street runs parallel to the Union Pacific line, and freight trains still pass through daily. Winters are severe, summers brief, and the town’s history includes both the Donner Party and Olympic skiing. Weather isn’t background here, it’s part of the town’s structure.

The Truckee Railroad Museum, located inside a repurposed caboose, documents how the transcontinental route shaped the town’s growth and layout. Nearby, Coffeebar Truckee serves espresso and house-made pastries in a space shared by remote workers and endurance athletes. Up the hill, Donner Memorial State Park preserves the site of the Donner encampment and features a stone monument with a base marking the height of the 1846-47 snowfall. For views of the Truckee River, the Legacy Trail offers a paved, five-mile path used by cyclists and long-distance skiers alike.

Dunsmuir

Dunsmuir sits in a canyon carved by the Upper Sacramento River, bordered by basalt cliffs and fed by alpine runoff. It was originally a boxcar stop called Pusher, named for the extra locomotive needed to haul trains up the mountain. Today it remains a functioning rail town with its original Southern Pacific depot and working turntable. The elevation is just under 2,300 feet, but the backdrop rises sharply, Mount Shasta fills the northern horizon like a fixed landmark. The town uses the slogan “Home of the Best Water on Earth,” sourced from glacier-fed springs and still delivered without chlorination.

The Dunsmuir Botanical Gardens, inside City Park, follow the riverbank and include native conifers, azaleas, and shaded footpaths below the tracks. Across the river, Tauhindauli Park preserves remnants of old rail lines and offers fly-fishing access directly below the bluffs. For swimming and falls access, Hedge Creek Falls sits just off I-5 and includes a short trail behind the curtain of water.

From fog-stung headlands to granite passes, Northern California’s small towns keep the state’s story at street level. Here, galleries inhabit shipwright cottages, mud baths bubble from volcanic seams, dairies bankroll facades, and rail whistles still set the clock. Choose one and you’ll meet the coast, forest, or foothills in their working clothes, oysters, timber, grapes, and snow. Stitch a few together and the highway becomes an archive instead of a blur.