How Phoenicians Produced Tyrian Dye From Snails

If you had lived in Ancient Rome, likely, purple wouldn’t have been a part of your wardrobe. This exclusive color was reserved for only the wealthiest citizens, as the dye was notoriously difficult to produce. Created in the coastal city of Tyre and made from the mucus of sea snails, the rich hue became a must-have commodity among the rich and powerful. As Tyrian purple grew in popularity, so did the Phoenician economy. On the back of the dye trade, the region’s society prospered and grew. Read on to discover how a humble sea snail from the Mediterranean Sea changed the economic and cultural landscape of Bronze Age Phoenicia.

How Tyrian Dye Was Made

The name Phoenicia, translated from the Greek as ‘purple land,’ shows the deep connection between the area, now modern-day Lebanon, and its history of dye production. Phoenicia was the birthplace of purple dye, first recorded in the 14th century BCE and made from the glands of shellfish.

There is a more mythical story about its origins, however. Legend has it that the dye was discovered by a pet dog belonging to the Phoenician god Melqart. While they were out walking on the beach with the nymph, Tyros, the pup stopped to chew a snail. On seeing the dog’s purple muzzle, Melquart was apparently so enraptured by the hue that he gifted Tyros a garment of that color.

Thanks to the Roman writer Pliny the Elder, historians have a more accurate record of how exactly the dye was made. First, workers harvested masses of Murex sea snails (it took thousands of the shellfish to produce just one ounce of dye). The snails were crushed and left to bake in the sun before the glands of each were extracted and placed in a pot full of brine, which was slowly heated for around ten days, during which time the liquid would turn a deep reddish purple. When it had reached the perfect tint, fabrics would be placed in the liquid to permanently stain them purple. The most exclusive fabrics were the ‘dibapha,' which translates as ‘twice dipped,' meaning they were immersed twice to produce a more lustrous purple hue.

The Color of Kings

Tyrian purple may have been pretty, but the smell certainly wasn’t. Dye manufacturing had to be kept downwind of urban areas, and the workers stank. Labour-intensive, smelly, and inefficient, the scale and complexity of the dye-making process meant that manufacturers had to charge a high price for their purple. And first-century fashionistas were willing to pay it. By 301 CE, Tyrian dye was literally worth its weight in gold, with a pound of pre-dyed wool costing one pound of gold.

Demand was high, not just because it was an attractive color. Tyrian purple was also known for its quality, as it was durable and didn’t fade. The rich, lustrous crimson quickly became a status symbol, beloved by royalty, church leaders, and other powerful people in society. Roman senators wore purple togas; however, a monopoly was later issued allowing only emperors to wear the color. In the Byzantine era, royal wives would give birth in a purple chamber in Constantinople known as a ‘porphyry’. This is where the phrase ‘born to the purple’ comes from.

The Economic Impact of Dye Production

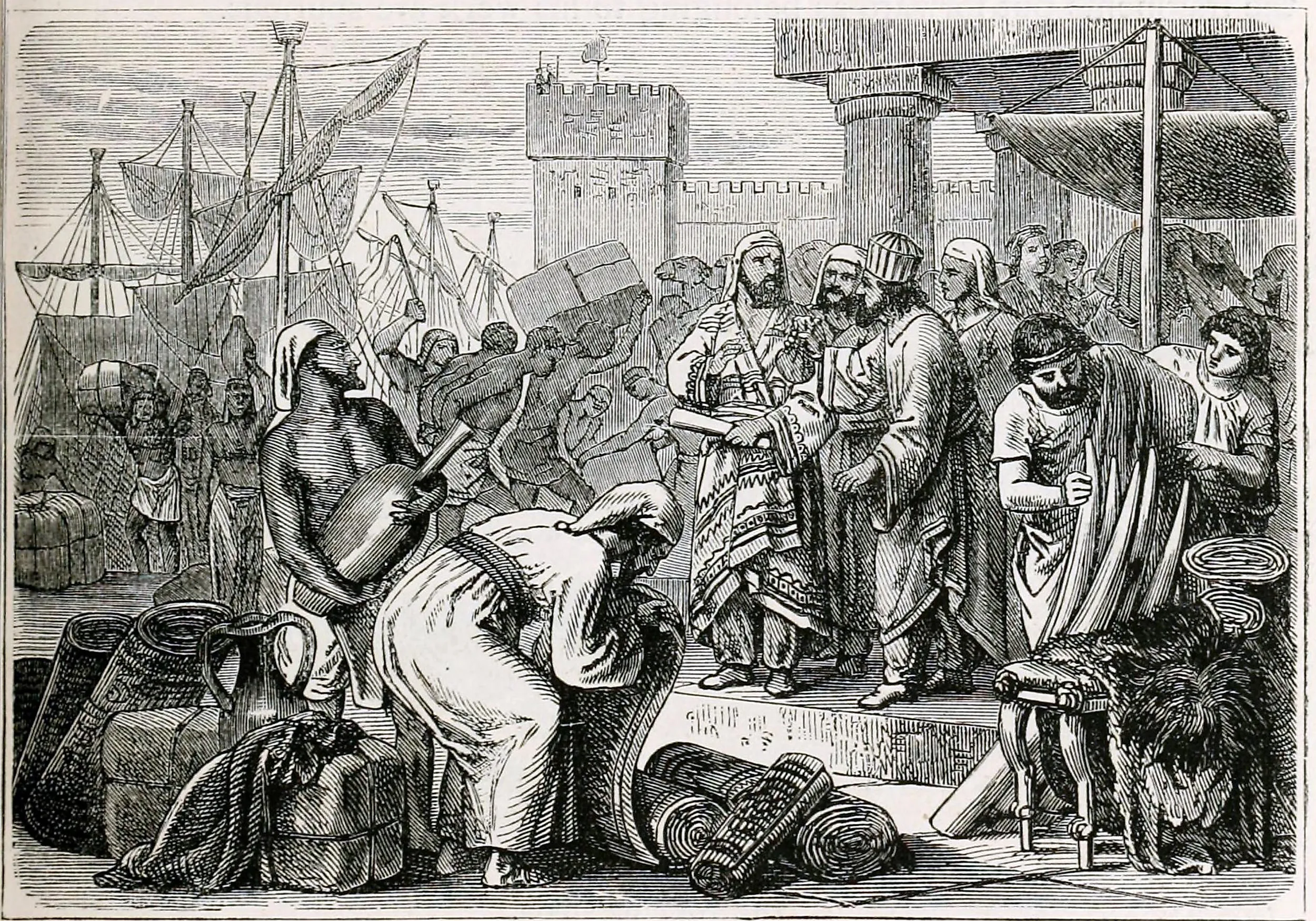

Mariners and merchants, the Phoenicians were already known as a thriving civilization, but their proprietary dye helped them expand further. In the search for more Murex snails, the harvesters went further afield, exploring the Mediterranean, the Iberian Peninsula, and North Africa.

Once they established an outpost in these areas, they set up trading routes that opened up more of the globe. These extensive networks brought Phoenician business to India, Africa, and Europe, and by far the most lucrative product shipped overseas was Tyrian Purple.

By the 10th century BCE, dye production centres were scattered along the Phoenician Coast, with the largest being at Tyre and Sidon. Today, tourists can visit Murex Hill in Sidon to see firsthand evidence of a huge dye production site. The 50-metre hill was formed from the remnants of sea snails discarded in the dye-making process.

The search for new supplies and new markets for their dye drove them onward, and by the 9th century BCE, the Phoenician empire had become one of the most powerful trading blocs in the world.

The End of an Era

Tyrian purple had a profound impact on ancient culture, society, and economies, but it didn’t last forever. In 640 CE, the main dye center, Tyre, fell to invading Arab forces, and imperial production was moved to Constantinople. In 1453, Constantinople fell to the Ottomans, and the industry was effectively over.

But the color purple wasn’t. In 1856, an English chemist named William Perkins was working on a cure for malaria when he made another discovery. When cleaning up his materials in the lab, he noticed that he had accidentally produced a dark purple liquid capable of dying cloth. Perkins quickly patented the color, which became known as ‘Perkins purple.' Perkins’ synthetic dye was much cheaper and easier to produce than the Tyrian shade and quickly dominated the market.

With a synthetic version readily available, the ancient process of making Tyrian purple was lost to time until, in 2007, an enterprising Tunisian scientist, Mohammed Ghassen Nouira, revived the process through a series of trial-and-error experiments. His work has been displayed in the British Museum and he sells the pigment to buyers across the world.

Purple is a symbol of luxury and power, a force that built an empire, and an ancient art. It is so much more than a pretty color. Next time you wear something in that shade, you are continuing a 3,000-year-old tradition that changed the world.