6 Strange Discoveries Hidden Beneath the Vatican

The Vatican is one of the most secretive places on Earth. Known officially as Vatican City State, it is the smallest independent country in the world, with a population of fewer than 1,000. It is entirely within the city of Rome, Italy, and has its own protection (the Swiss Guard), postal service, flag, and national anthem. The Vatican is also the headquarters of the Roman Catholic Church. The Pope is the supreme leader of the Vatican and of Catholics worldwide. The Vatican serves as the Holy See, the governing body of the worldwide Catholic Church. Both Catholics and non-believers flock to the Vatican every year to see St. Peter’s Basilica, the Sistine Chapel, and the various Vatican museums.

On the inside, and underneath, things get a little strange. Over the years, reality, rumors, and conspiracy theories about the Vatican and the Pope have blended to the extent that many people believe mysterious things are happening within the country’s limits. On top of this, several strange discoveries have been made that fuel these theories. Keep reading to learn more about these discoveries.

A Hidden City of Tombs Found Under St. Peter’s Basilica

Construction on St. Peter’s Basilica began in 1506 under the watchful eye of Pope Julius II. It was completed only in 1615 under Paul V. The building is in the shape of a Latin cross and features a dome at the crossing above the high altar. The basilica is considered an excellent example of Renaissance architecture and the most significant building of its time. But the beauty above hides something else below.

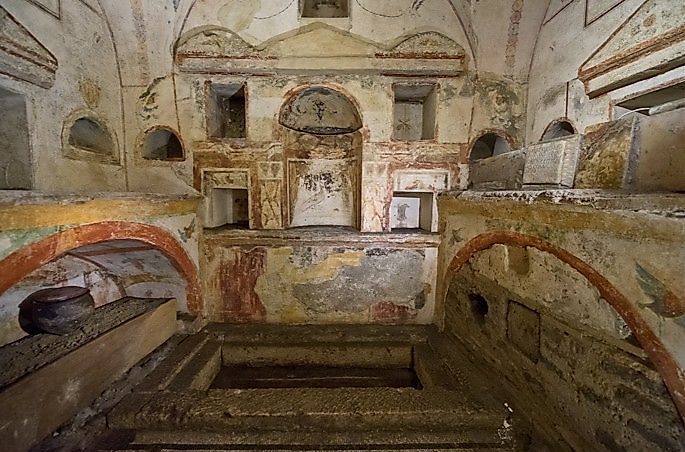

St. Peter’s Basilica sits on top of a collection of tombs of the wealthy and elite. After the great fire of A.D. 64, Nero accused Christians of igniting the flames. Turning the attention completely away from himself, he persecuted the Christians, allowed wild animals to kill them, burned them at the stake, and crucified them. St. Peter, the first bishop of Rome and the leader of the Apostles, was also crucified, and it is believed he was buried on Vatican Hill. Emperor Constantine ordered the original basilica to be built on this burial ground, so the present building still sits on the necropolis traditionally associated with St. Peter’s burial. The necropolis was uncovered during excavations in the 1940s when researchers found tombs, mausoleums, and what they think is St. Peter’s grave.

The Possible Bones of St. Peter Linked to a Buried Shrine

Pope Pius XII authorized the secret excavations of the 1940s. The goal was to find St. Peter’s tomb. The excavation process was initiated after the death of Pope Pius XI in 1939, who wanted to be buried in the Vatican grottoes. The grottoes are near the site where the tomb is said to be. For the burial to take place as requested, the grottoes had to be lowered. When they were brought down, archaeologists discovered the mausoleums and other artifacts. Pope Pius XII then decided to proceed with a full excavation of the necropolis to determine once and for all whether St. Peter was in fact buried there. The digging was kept under wraps for a full decade, until 1949, when rumors of an excavation began circulating. The excavation yielded incredible results.

Archaeologists discovered a 2nd-century funerary monument built into what is known as the Red Wall. This monument, or shrine, called the Trophy of Gaius, was located directly beneath the basilica's high altar. The niche under the shrine turned up empty, but a hidden repository was found nearby in a wall adjacent to the Red Wall. The repository was lined with marble and labeled Loculus 9. Inside, researchers found fragments of human bones, mixed with animal bones and debris. Forensic analysis in the 1950s found nothing conclusive regarding the human bones. However, a second study conducted in the 1960s revealed that some of the bones belonged to a male aged 60 to 70, with a large build. It was also announced that, during excavations, the discovery of the nearby Wall G included a Greek inscription in charcoal. The inscription read ‘Petros Eni’, which means ‘Peter is here.’ Researchers further state that the earth encrusting the human bones matched the soil from the 1st-century grave pit beneath the shrine. Pope Paul VI announced in 1968 that the remains were ‘convincingly identified’ by the Vatican as those of St. Peter.

The Obelisk and the Ashes of Caesar

St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City holds the so-called Vatican Obelisk. Caligula brought the obelisk from Alexandria, Egypt, to Rome around 37-40 AD, where it was placed in the Circus of Nero (an ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium built in the 1st century AD, which is also located beneath St Peter’s Basilica). The discovery was not as much the obelisk as its contents. Until it was moved and opened by the order of Pope Sixtus V, it was believed that the bronze globe at the top of the obelisk held Caesar's ashes. After it was opened, it was found to contain only dust and dirt. The globe was then removed and can now be seen at the Capitoline Museums in Rome.

This anti-climax is completely overshadowed by the moving of the obelisk itself. The move was an incredible feat of engineering at the time, requiring over 140 horses and 800 men. The workers were given a strict ‘code of silence' order while moving the stone. If someone had shouted or caused a distraction, the workers’ coordinated movements would have fallen apart, potentially leading to the obelisk falling and crushing them. As for what happened to Caesar’s ashes, its final destination remains unknown. Some experts believe that it may have been placed in the family tomb of the Julii.

The Tomb of the Julii and Pagan Art

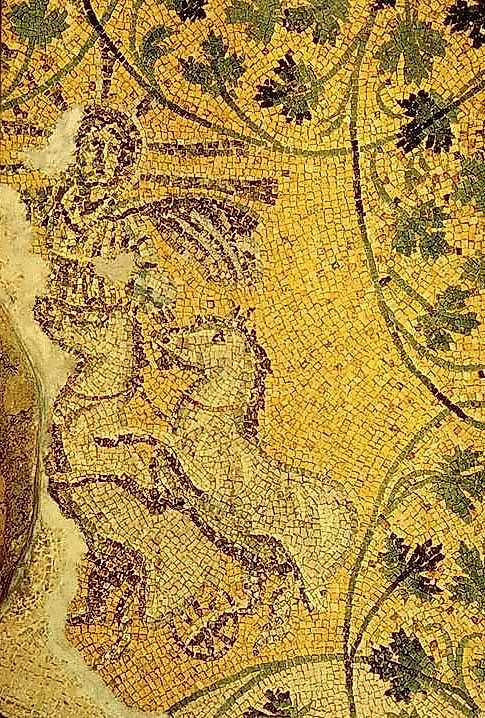

Speaking of the Tomb of the Julii (Mausoleum M), this site is one of the most significant for understanding the link between the pagan Roman world and the advent of Christianity. The secret excavations revealed pagan Roman mausoleums, including the Tomb of the Julii. The tomb dates to the late 2nd or early 3rd century and features a gold mosaic ceiling. The first impression the tomb made was that of a tribute or homage to the Roman Sun God, Helios (or Sol Invictus), driving a horse-drawn chariot across the sky. But when historians and researchers looked closely, they realized that the theory does not hold water. The figure in the mosaic is surrounded by grapevine tendrils, which are a common Christian symbol.

As such, researchers concluded that the Julii family used syncretism to hide their Christian faith. Because being Christian was punishable by death during the Roman Empire, the family decided to depict Christ with the solar rays of Helios. This allowed them to honor Christ while hiding their faith from Roman officials. The Tomb of the Julii was hidden for more than 1,600 years because Emperor Constantine ordered that the roofs of pagan tombs be smashed in A.D. 318. The rooms had to be filled with dirt to form the foundation of the original basilica. This means the ‘cemetery’ was buried, and the Christus Helios mosaic was preserved until it was unearthed during WWII.

City of the Dead Discovered Beneath a Vatican Parking Lot

Not all the strange Vatican discoveries were made during the Second World War. As recently as 2003, Vatican workers excavating a hillside for a new multi-level parking garage at the Santa Rosa gate struck more than just dirt. They happened upon stone and marble, which led to the discovery of the Via Triumphalis Necropolis. What they had inadvertently found was a 10,000-square-foot ‘Street of the Dead’ that had been buried under the northern slope of the Vatican for many centuries.

The Via Triumphalis site is not the same as the necropolis found under the basilica. The basilica graves were meant for the elite, while the parking lot site consisted of tombs belonging to ‘blue collar’ workers of the Roman Empire. These workers included a horse trainer for the Nero Circus, a theater set designer, and a postal clerk. The parking lot discovery was also eerie since the tombs were unnaturally well preserved thanks to mudslides from the Vatican Hill. The mud sealed the frescoes, mosaics, and marble until the workers hit it. The saddest find in the parking lot site is the tomb of a young boy named Alcimus. The boy was in charge of the theater scenery for Pompey’s Theater. The Vatican has since installed glass walkways over the site for visitors who want to see the remains of those who once lived and died in the streets of Rome.

Thousands of Bones in the Teutonic Cemetery

Perhaps the most unsettling discovery about the Vatican occurred in July 2019. Following a lead in the cold case of the disappearance of Emanuela Orlandi, who disappeared in 1983, Vatican authorities opened two 19th-century graves in the Teutonic Cemetery. The cemetery is a restricted burial ground that sits a couple of feet away from where the Pope resides. The tombs belonged to the Princesses Sophie von Hohenlohe and Charlotte Frederica of Mecklenburg. Once opened, the investigators were shocked to find the tombs empty. Not only was there no trace of Orlandi, but there was no sign of the remains of the princesses who were supposed to be buried there more than a century ago.

Workers were ordered to inspect the surrounding structure, and they discovered a stone manhole that led to two underground ossuaries. These ossuaries sit beneath the floor of the Teutonic College. Inside them, forensic scientists found thousands of bone fragments clumped together. Unsurprisingly, when the word spread of this discovery, it sparked international outrage in the midst of conspiracy theories about secret Vatican burials. It took several days of sorting through the remains to help calm the backlash. Professor Giovanni Arcudi and his team concluded that the bones discovered were much older than those of Orlandi would have been. They also found that the bones likely belonged to people buried in the cemetery who were moved during renovations in the 1800s.

Peeling Back the Layers Of The Vatican’s History

From the outside, the Vatican is a stunning place that incorporates incredible architecture and polished marble. But beneath the surface, several finds intertwine with the place’s history. For many centuries, the Church did not merely replace the Roman world, but literally sat on top of it. The excavations over the years have shown that a persecuted minority rose to become a global power. Today, the ancient stones of the Vatican still hold many secrets. Whether they will be uncovered remains to be seen.