What Is Pangea?

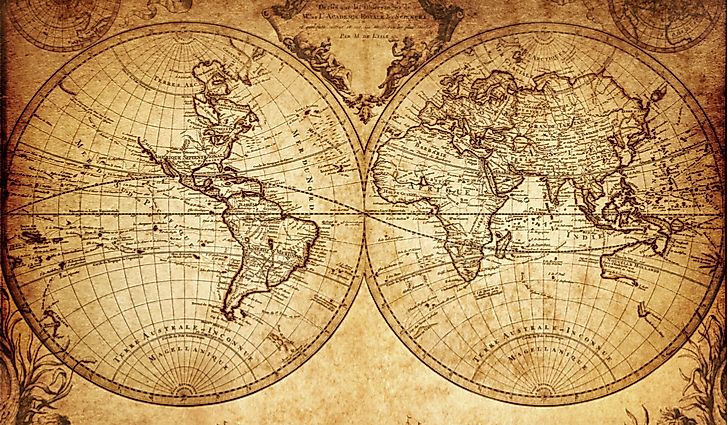

- Pangea was once a single unified landmass surrounded by a solitary sea called Panthalassa.

- Pangea broke apart in three major stages, as rifts appeared within the Earth's crust.

- It is estimated that Pangea was formed some 335 million years ago.

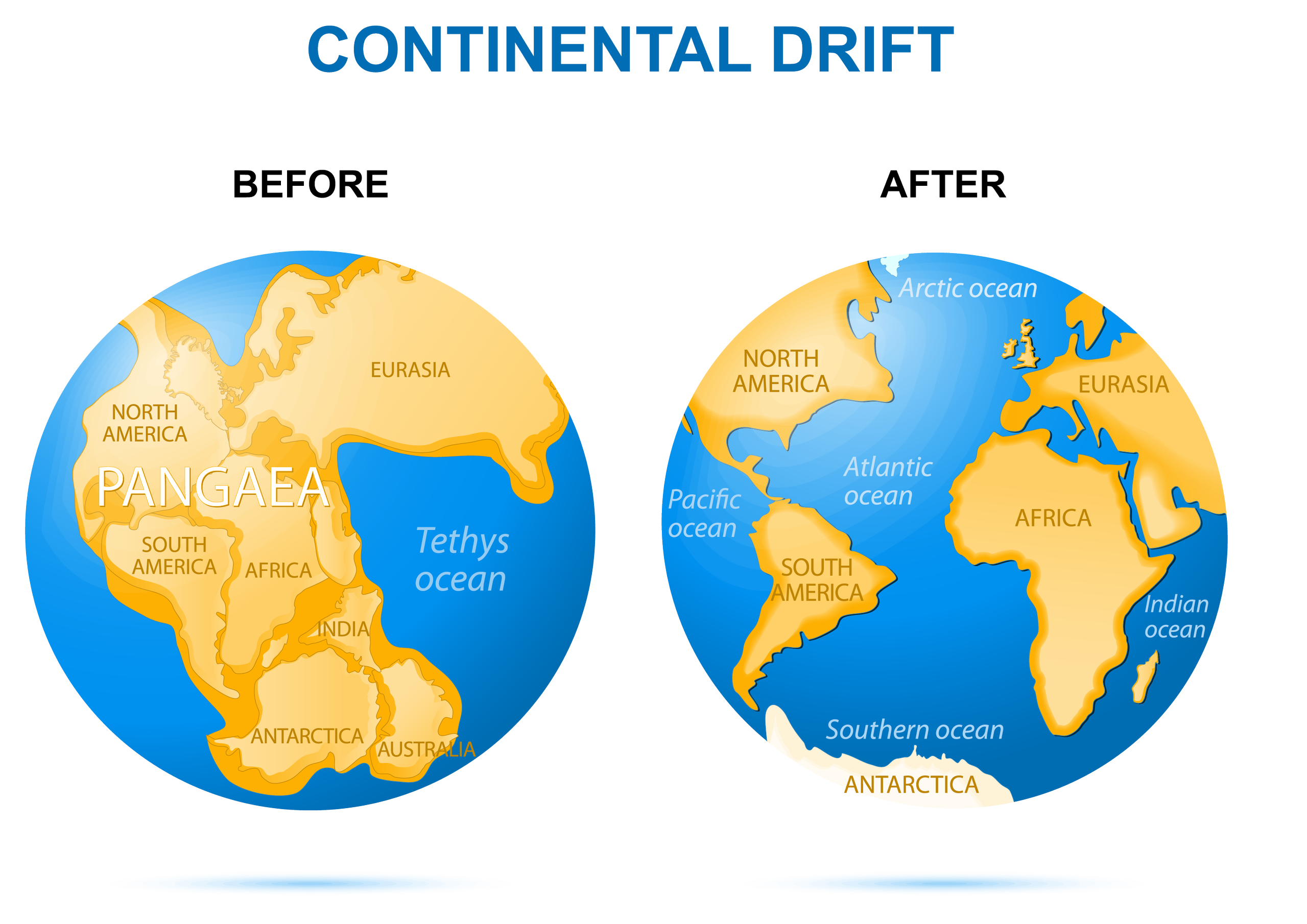

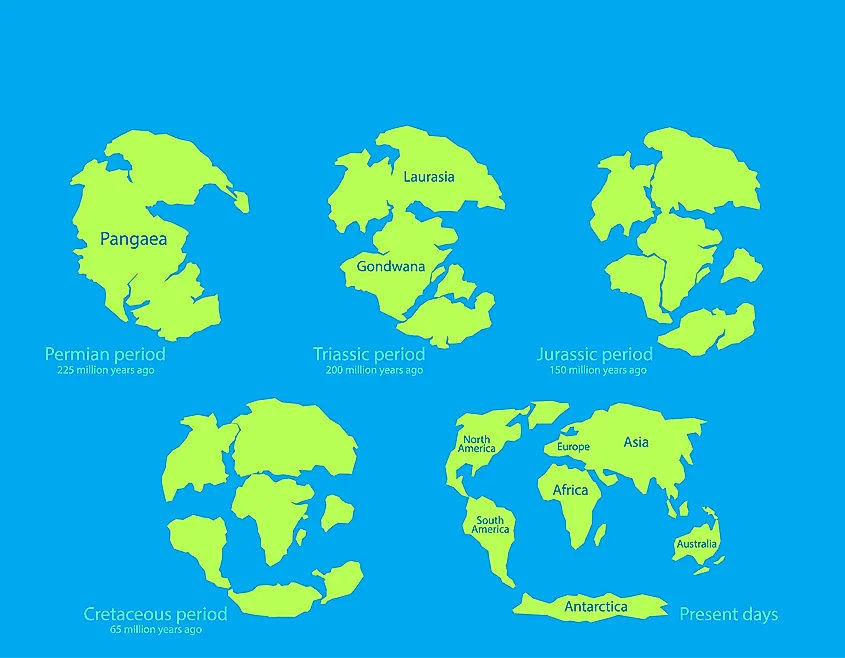

Nearly 300 million years ago, the geography of the Earth was drastically different than it is today. This time period, between 280 million and 230 million years before present, was known as the late Paleozoic to early Mesozoic Era, and it was during these periods that Earth consisted of one collective ocean, called Panthalassa, and one single land mass or supercontinent known as Pangea. This name stems from the Greek word ‘pan’ meaning all or whole, and Gaia which refers to Mother Earth.

Pangea is estimated to have formed around 335 million years ago, but it was likely not the first or only continental configuration. This formation probably resulted from the merging of other continents and landmasses on Earth. This assumption is partly based on the knowledge that continents and tectonic plates—massive segments of the Earth’s crust—are perpetually moving, either drifting apart or colliding. Although this process is ongoing, it occurs at a rate so gradual from a human perspective that we cannot observe any significant changes within a single lifetime or even throughout human history.

Proof Of A Single Landmass

Although the creation and eventual breakup of Pangea is speculative since humans did not exist then, extensive evidence supports these theories. A deeper understanding of plate tectonics has enabled scientists to better detail movements and patterns in the Earth’s crust, surpassing earlier theories of ‘Continental Drift.’ The formation of mountain ranges, rift valleys, and volcanic activity around plate boundaries and fault lines has significantly advanced scientists’ comprehension of tectonic plate movement and drift. These geological phenomena indicate deeper movements within the Earth’s crust, which can be traced to reconstruct a historical overview of continental movements, crustal fractures and reforms, along with shifts that have occurred over time. Furthermore, there is evidence supporting that all continents were once a single megacontinent, namely Pangea. This is especially evident in fossil records of flora and fauna found worldwide. Similar or identical animal fossils have been discovered across widely separated continents, suggesting, as outlined in the Pangea theory, that these landmasses were once contiguous, facilitating the natural movement of species. These fossils often cluster along the edges of countries or continents that were once connected. For instance, the eastern coast of Brazil and the western edge of Africa share fossils of the same reptilian species, indicating that these landmasses were once united, with the creatures inhabiting an area that subsequently divided.

The Separation Of Pangea

The Pangea landmass began its slow disintegration approximately 175 million years ago. This gradual splitting of the massive continent happened in stages, marked by the emergence of rifts and fissures. Primarily attributed to volcanic activity in the Earth’s mantle—the semi-liquid layer beneath the crust—these fissures formed as heat and pressure built up beneath the Earth’s plates. When the pressure exceeded the capacity of the crust, magma, or molten rock, would surface or create rifts. This process initiated the splitting of the Earth and the gradual movement of landmasses apart. Continuing today, you can observe this activity along fault lines and plate boundaries, where heightened activity beneath the surface occurs. These movements and pressures result in significant geographical transformations on Earth, including volcanic eruptions, mountain formations, and even the shifting of continents. What was once referred to as 'continental drift’ is now explained through the theory of plate tectonics, which describes large sections of the Earth’s crust, known as the lithosphere, fitting together like loose puzzle pieces. Unlike a static arrangement, these pieces float and drift on a semi-molten rock layer beneath. This magma enables the plates to shift, move, and collide—albeit slowly over extensive timescales. Plate movements predominantly happen along ocean ridges, subduction zones, and fault lines, indicating ongoing motion. This subsurface activity also contributed to the breakup of Pangea. Insights from plate tectonics shed light on the idea that the breakup of Pangea did not occur suddenly, but rather unfolded gradually in three major stages, along distinct rifts.

Phase One

As indicated, the first main phase, estimated to have been 180 million years ago, saw the creation of what we now know to be the central Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean. The rift began in the Tethys Ocean running Westward to the Pacific. Cracking and fissures within the crust created multiple failed rifts along this line, resulting in the creation of the North Atlantic Ocean as North America began to split from Africa. Later, rifting occurred to the south, as the supercontinent known as Laurasia - (what we now know to be North America, Europe and Asia) drifted northward and rotated, resulting in the South Atlantic.

The area along Africa’s eastern coast also experienced a great deal of rifting. At the time, Antarctica and Madagascar were joined to Africa along the coast. As these rifts began to form, continents began to drift, and the Indian Ocean was created.

Phase Two

Phase two of Pangea’s separation occurred roughly 150 million years ago. At this point, the Earth consisted of Laurasia - North America, Europe and Asia - and Gondwana, which was Africa, South America,India, Antarctica and Australia. This phase primarily concerned Gondwana, and began the separation of these individual continents from their former landmass body. A subduction, or dropping in the Earth’s crust along the Tethyan trench, is thought to be the primary cause of Africa, India and Australia’s first big shifts northward, thus creating the South Indian Ocean. Later, a landmass dubbed Atlantica - current day Africa and South America - broke from Gondawana creating the South Atlantic Ocean, and over time this land mass drifted westward.

The Indian Ocean was also born at this time, as Madagascar and India disengaged from Antarctica and were pushed further north. India was still only just adrift of Africa at this time, and still connected to the island of Madagascar. A rift began to form within this land mass, and it eventually broke India and Madagascar apart. India was propelled away from its original African anchor, all the way up into Eurasia, further closing the Tethys Ocean. India collided with Eurasia approximately 50 million years ago, and it was this forceful collision that was the cause of the Himilayan mountains, which show the buckling and jarring of the Earth's crust along the plate lines there.

To the east, smaller fractures began to separate New Zealand, and New Caledonia from Australia proper. Thus, the Coral Sea and the Tasman Sea were born, as well as a number of cracks and smaller rifts where much volcanic activity still occurs.

Phase Three

The third phase of Pangea’s break up is what led, in a general sense, to the map of the Earth as we know it. Of course the tectonic plates are constantly in motion, but because this change is slight, the results of phase three are much the same as the position of the continents now.

This phase saw the remainder of the ‘multi-continent’ land masses breaking up and shifting positions. In the north, Laurasia split apart into Laurentia (North America and Greenland) and Eurasia. This resulted in another sea, known as the Norwegian, and occurred roughly 50 million years ago. Australia also fully separated from Antarctica at this time, and was pushed northward. The continent has been steadily shifting north ever since, and is expected to eventually collide with eastern Asia.

At the same time, South America shifted upward to the north, pulling apart from Antarctica. Smaller changes could be seen at this time as well, including the widening of the Gulf of California, the formation of the Alps, and fissures and rifts in the east, bringing Japan and the sea of Japan.

By fitting the continents back together jig-saw like, it is easy to see where the fractures and rifts tore the once singular continent of Pangea into its various parts, which drifted, rotated and reconnected over time.