This New Hampshire Town Is Older Than the State Itself

In the spring of 1623, just as the Mayflower settlers were struggling through their third harsh winter in Plymouth, two brothers stepped onto the rocky shores of what would become Dover, New Hampshire. Edward and William Hilton, fishmongers from London, had sailed across the Atlantic with a handful of companions to establish a fishing colony at the confluence of the Bellamy and Piscataqua rivers. Little did they know that their modest little settlement would outlast empires, survive Indian raids, and witness the birth of a nation.

Today, not only is Dover New Hampshire’s oldest permanent community (and the seventh oldest in the country), it predates the forming of the state itself by over 160 years. New Hampshire joined the Union in 1788 and was the ninth state to do so.

The town also reinvented itself countless times. Starting as a fishing outpost, it served as a frontier garrison, a shipbuilding center, and a mill town, and ultimately played a significant role during America's Industrial Revolution. Walk through downtown Dover today, and it's easy to forget that these same streets have witnessed nearly four centuries of American history.

Early Settlement

The Hilton brothers arrived at what they called Hilton's Point (now Dover Point) as part of the Council for New England's ambitious colonization efforts. Unlike the religiously motivated Pilgrims to the south, these were practical men seeking profit from fishing the teeming waters of the Piscataqua River. Their choice was very deliberate as the point offered deep water access for ships, protection from storms, and proximity to vast schools of cod and other commercially valuable fish.

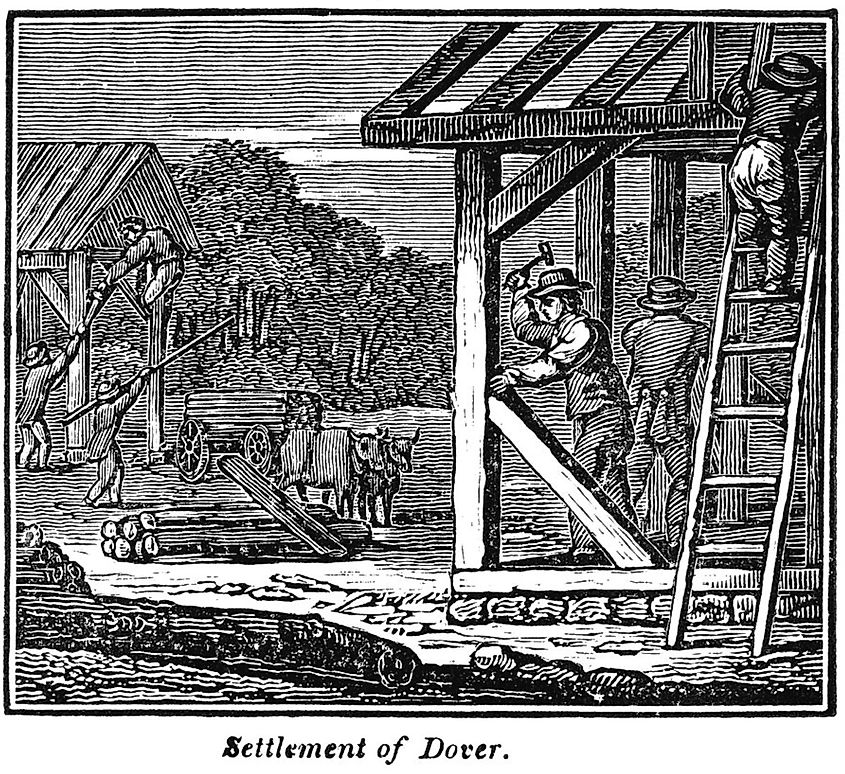

The early years certainly tested the resolve of these first settlers, whose crude huts and fish-drying platforms clung to the riverbanks. By 1631, the entire settlement consisted of just three houses. William Hilton, drawing on his experience from his hometown of Northwich, England, established a salt works to preserve their catch for the long journey back to European markets. The work was backbreaking, the profits uncertain, and the isolation profound.

As important as the fishing was, however, it was the potential of the land itself that sustained these first settlers. Dense forests provided timber for building and export, rivers offered sites for future mills, and the soil, once cleared, proved suitable for farming. By 1633, the settlement had grown enough to attract the attention of English Puritans who purchased the plantation and encouraged immigration from Bristol in England, lending the settlement yet another name.

Name Change and Transformation

In those early decades, the settlement's identity shifted as frequently as its name. In 1637, the name changed again, this time to Dover for an English lawyer known for resisting Puritanism. Two years later, it changed again, this time to Northam after the hometown in Devon of the area’s preacher. Interestingly, these constant name changes reflected the turbulent politics of the times, with distant English nobles and Massachusetts authorities vying for control of the profitable region.

While it’s not known exactly when the name “Dover” was settled on, it was beginning to stick by the 1640s when it was transformed from a coastal fishing station to a larger inland settlement. Its strategic importance also grew as the fur trade between European settlers and Native Americans took off. While relationships with native peoples were at first amicable, things changed in 1676 during the chaotic final months of King Philip's War. Though New Hampshire remained largely neutral in this conflict between settlers and the native populations, hundreds of Native American refugees from Massachusetts arrived seeking shelter with the local Pennacook.

Massachusetts authorities demanded their capture and return, and about 200, including some Pennacook, were sent to Boston; seven or eight were hanged, and others sold into slavery in the Caribbean. The Pennacook never forgot this betrayal, setting the stage for one of the bloodiest events in Dover's history. Feeling cheated, a group of angry Pennacook sought revenge, killing several settlers in and around Dover in what came to be known as the Cochecho Massacre.

Dover’s Early Economy

From its earliest days, Dover's economy revolved around its waterways. Fishing gradually gave way to shipbuilding, and by the 1700s, Dover’s maritime industries were prospering along the Cochecho River. Here, master shipwrights crafted vessels that would sail to the West Indies, Europe, and beyond, carrying with them New Hampshire timber, fish, and other products to global markets.

The first real transformation, however, came about with the harnessing of water to power the first sawmill at Cochecho Falls in 1642. Gristmills followed, grinding corn and wheat for a growing population. Dams and millraces were added, channeling this newfound power to an ever-growing number of enterprises.

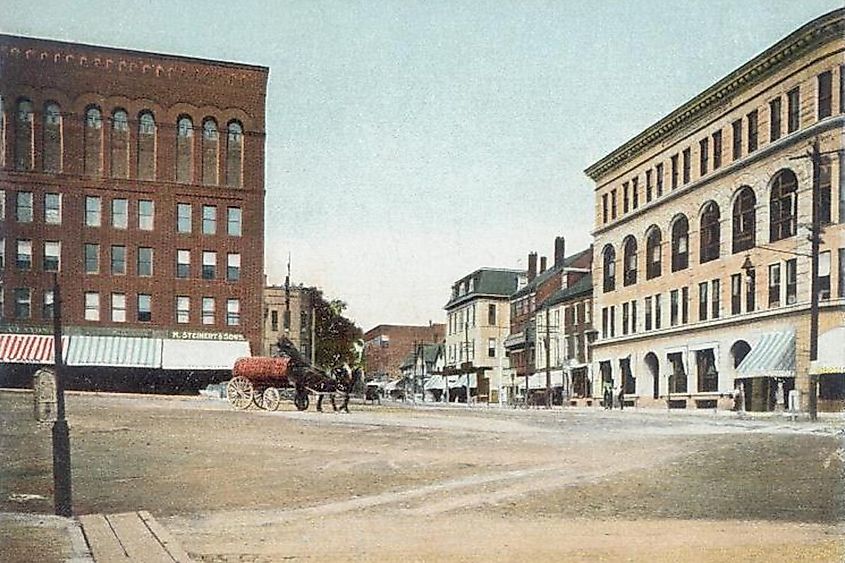

Dover's location at the head of navigation on the Cochecho River also helped its commercial growth. Goods from the interior including timber, agricultural products, and furs flowed through Dover to England and international markets, with rich merchants building substantial homes and warehouses with their new found wealth.

The Industrial Revolution

The dawn of the 19th century saw Dover at the forefront of America's Industrial Revolution, with local investors building the Dover Cotton Factory in 1815. Although a modest beginning, it would transform Dover into one of New England's major manufacturing centers. Reorganized as the Cocheco Manufacturing Company in 1827 (the misspelling was a clerical error that stuck), Dover became a leading producer of cotton textiles in the nation by the early 1830s.

The cotton industry also became a major employer, as mills attracted hundreds of young women from New Hampshire and Maine. These "mill girls" lived in company-owned boarding houses, worked 12-hour days, and earned wages that, while meager by today's standards, offered at least some economic independence, a first for many.

Preserving Dover’s Past

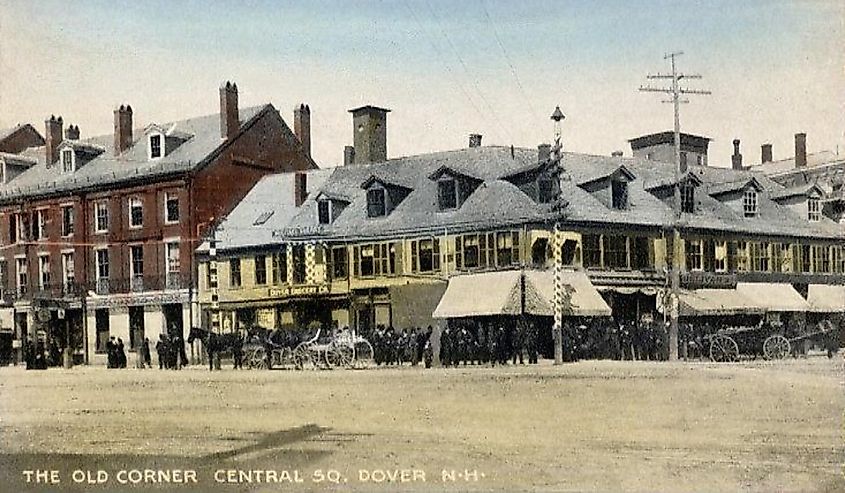

Visit Dover today, and you will find a community that has done a great job of preserving its past. Several attractions have sprung up to share this fascinating history, most notably the Woodman Institute Museum. Established in 1916, its large collection spans Dover's history from the time of the Hilton brothers and includes Native American artifacts and mill memorabilia. It is also where you will find the Damm Garrison, one of the few surviving garrison houses from Dover's frontier days.

The transformation of the Cocheco Mills is another great example of preservation. Built in 1822, these massive brick structures once employed thousands of textile workers but now house technology companies, restaurants, a brewery, and residential lofts. The mill yard has also gained new life as a gathering place for community events and farmers' markets.

Other highlights include the Children's Museum of New Hampshire, which occupies a former mill building from the 1920s; Henry Law Park, a green space along the river where mills once dumped their waste; and the summer-long Cochecho Arts Festival.

Outside of town, Hilton Park at Dover Point is where the settlement began and boasts views across the Piscataqua River that have changed little since the 1620s. Another relic from the past, the Pine Hill Cemetery has been a burial place since before 1700 and contains the graves of settlers who knew Dover when it was still a frontier outpost. It and other sites are connected by a network of heritage walking trails and interpretive signage explaining and highlighting the town’s landmarks.

One of New England’s oldest and most interesting small towns, Dover has survived and thrived through four centuries of change. From English settlement through Indian wars and from agricultural community to industrial powerhouse, each era left an indelible mark on the town, making it a wonderful place to visit today… and no doubt for years to come.