How All Roads Did Lead To Rome

In 125 AD, the Roman Empire, the largest civilization in the world, sprawled from north to south, from Great Britain to Morocco, and east to west, from Iraq to Portugal. Its economy was fueled by war, its focus was conquering, and the military was the main means to achieve expansion. With enormous resources put into the expanding empire, its dirt roads could no longer sustain the growing empire.

Rome engineered itself with a network of paved roadways that eventually covered 400,000 km (248,548.47 miles), with over a quarter considered public roads. Constructing roads for the legions to move with ease and efficiency also helped people and goods travel quickly from one end of the empire to the other. Improved transport of commerce and communication were the key factors in maintaining an empire.

But did all the roads lead to Rome? The answer is complicated. Let us look at these Roman roads first in an express time travel through the road construction period in the Empire. At the zenith of its control, the road network stretched from the sun-bathed Rock of Gibraltar to Mesopotamia's marshlands.

Behind the Road Construction: Military

Funding the military was part of the effort to achieve victory, but the difficult dirt paths, especially in the provincial lands, slowed the provision of military equipment, soldiers, horses, and other necessities. The Romans strategized that, having to cover great distances and fight battles along the way, the troops would be more efficient with easier movement and faster delivery of the necessary war items.

To aid the military and for administrative purposes throughout the colonized land, the Romans paved roads through the provinces and the newly acquired cities, which were established as Roman colonies. Paving the roads helped efficiency by reducing travel time and marching fatigue for the troops, allowing them to be at their best where they were needed. Covering 20 miles a day, they could prevent outside threats and cool down internal uprisings, thus protecting the empire and helping it expand.

Did All Roman Roads Lead to Rome?

Not all, but the most important ones did. The endurance of Roman roads, a real engineering marvel, stands the test of time, with a legacy in that a lot of Europe's road infrastructure today links major cities to the Italian capital.

Many of Europe's freeways in the late 20th and early 21st centuries followed the same routes. Currently, motorways are built away from populated areas, a departure from the old Roman route construction.

How Did All the Roads Lead to Rome?

Ancient routes, like modern ones, were based on logic to connect two points on a map—in this case, places that were both part of the Roman Empire. Roman roads were largely concentrated on Rome and partly on what was most efficient for the military. When barbarians, or non-Romans, were still resisting occupation, the Romans preferred safer, less direct routes, including dense woodlands and mountains.

After annexation, the main roads of the Roman Empire were built straight whenever geographically possible between the important cities for open travel when safety was no longer a concern. While the main roads connecting important cities all ended or started in Rome, they were designed for the movement of wheels and animals, not to go from one place to another. Essentially, the paved roads were the vital connection to speed up trade and transport new troops and provisions to supply the military on the frontline.

Logic

As the Roman Empire grew, so did the population in Rome, increasing rapidly to one million people, which required trade support to transport goods to high-density areas. The new roads made it easier to access every corner of the Empire, including the most isolated territories to get supplied, reinforced with troops, and any emergency that needed a fast response.

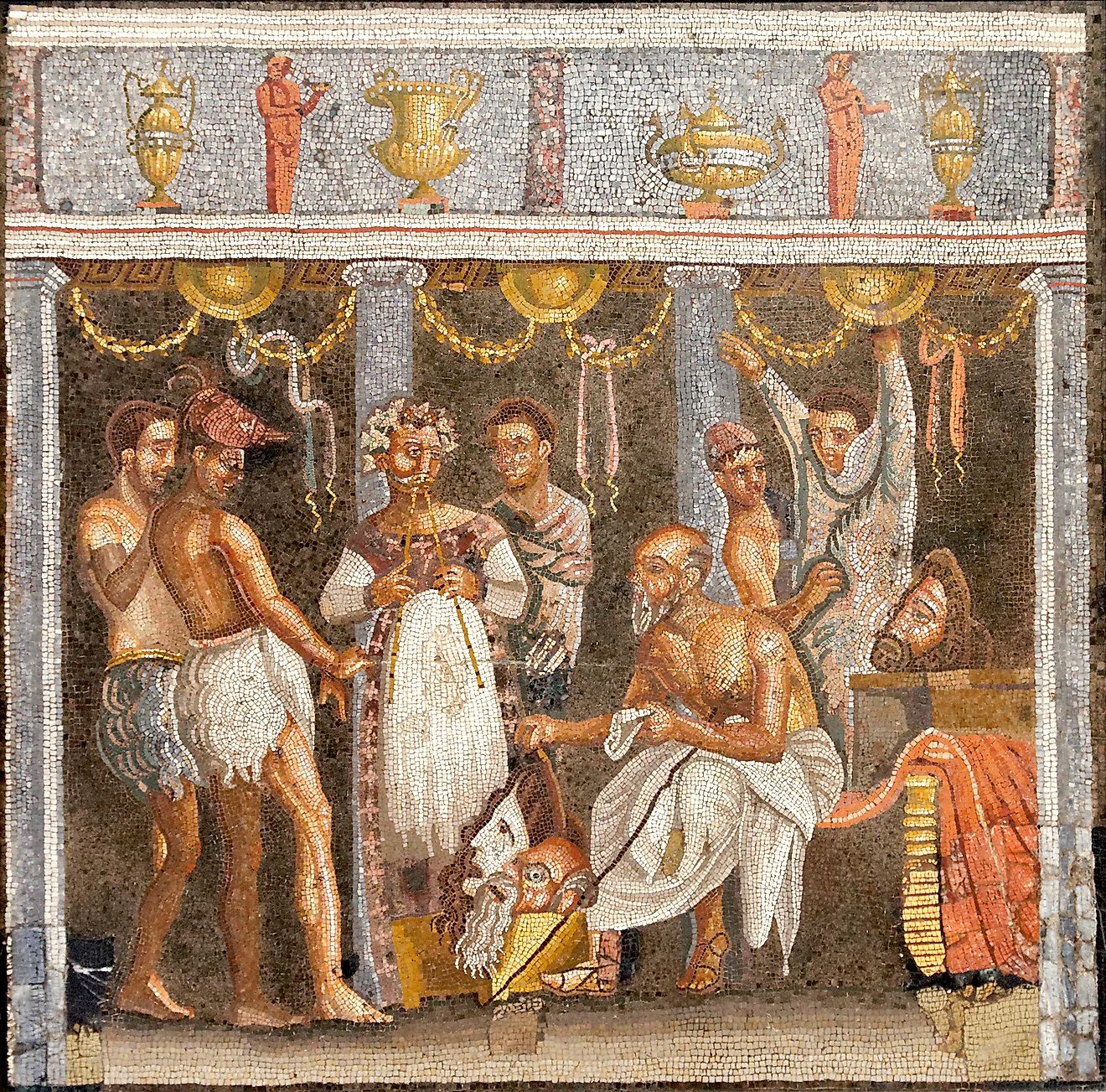

Facilitating the swift movement of carts, the goods speed effortlessly across the land and regions. These were life necessities such as foodstuffs like fish, cereals, salt, and olive oil, and animal products like leather and hides, as well as crafts of all mediums and construction materials like marble, wood, and silver. Furthermore, the paved roads helped with mapping to understand the scope of the empire, maneuver around enemies in war, and maintain order in the country.

Types of Roads

There was differentiation between the types of roads, all called "viae," related to the English word for "way." Some were vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, and others were less important. The Roman command was quality-oriented, with the ideological objective of building roads that would not need frequent repair.

There were three types of roads constructed at this time, with the first type called Viae Publicae, Consulares, Praetoriae, or Militares Roads. These roads, running to the sea, a public river, a town, or another public road, were common-use highways or main roads, constructed at common expense and along common soil.

Viae Privatae, Rusticae, Glareae, or Agrariae included paved and unpaved private or country roads, constructed privately on their soil, with the power to dedicate them to whoever could use them. Viae Rusticae were the secondary roads, while Viae Vicinales, the last type, were the ancient Roman village or district roads, as well as crossroads through or towards a village.

Via Appia

Via Appia—the public roads—were constructed using taxes from neighboring landowners and with soil vested in the state under Appius Claudius, who died before Via Appia was finished. The Senate took over the allocation of funds to complete the project, with the original stretch costing around 259 million sestertii, whereas one million sestertii is about 2500 metric tons of wheat. Rome received some 435,446 tons of wheat and 174.2 million sestertii, gold, silver, and iron annually during the ancient Roman period.

Despite high costs, the Roman Republic benefited tremendously from Via Appia, the backbone of a protected, effectively functioning, and growing Roman economy. Via Appia, an excellent feat of engineering, stands the test of time in continuous usage as well as being the site for several events and traditions, with catacombs, various basilicas, and tombs along its stretch. Today, Via Appia Antica is a park, once used for the Olympic Games marathon course, and you can explore on a bike amid its monuments like statues, mausoleums, and broken villas from the last 2,000 years.

Modern Research

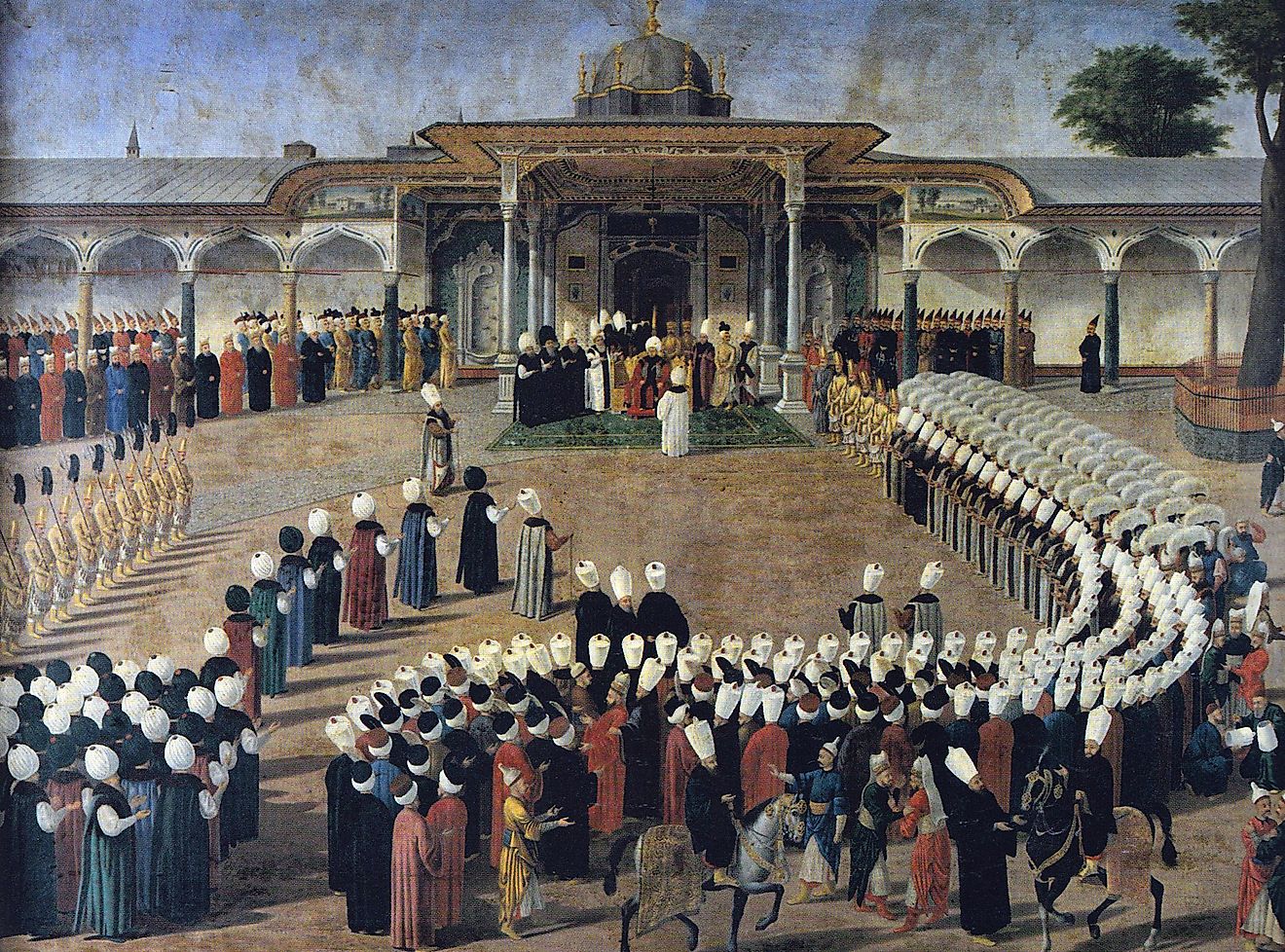

In a 2015 experiment to see if all roads lead to Rome, a team of German researchers and designers dropped a uniform grid of some 500,000 points in random spots across the European map. According to an algorithm that calculated the best route to Rome using modern routes from each of those starting points, the more a segment was used, the bolder it appeared. The resulting map showed a mesmerizing web of roads that led to Rome, and just as important, they led through major cities like London, Constantinople (Istanbul), and Paris—all part of the ancient empire.

While the Italian capital was the center of the exercise, if looking for the fastest route from the 500,000 points to other major European cities, the resulting map would be similar in the vast array of roads leading to those cities without touching Rome. According to researchers, the logic of traveling through the ancient empire was similar to that of a modern country building roads to connect people and things. The answer to whether all roads lead to Rome is that it depends on the road's importance. Roman roads were built primarily for military purposes—a consistent priority to protect and expand the empire—with development spurred to minimize routes and save time.

Trivia

So what is behind the expression "All roads lead to Rome?" Used since the Middle Ages to refer to the fact that the Roman Empire’s roadways radiated from the capital, the maxim is still somewhat relevant today.

In Europe, almost all roads lead to Rome, according to cartographers. However, with the world being much bigger than either Europe or the self-centric ancient empire, all roads do not lead to Rome since roads are unable to cross the vast oceans as of yet.

Interestingly enough, there are 10 cities in the United States called Rome and a city called Rome or Roma on every continent—the everlasting legacy of the Roman Empire. The expression is also an idiom, meaning that all methods of doing something lead to a common result.

Conclusion

Paved road construction began thanks to the growing Empire, which focused on expanding the network of paved roads for military efforts. It facilitated the Empire's growth as the backbone of achievement and convenience, which eventually made the Romans the largest and most successful civilization of all time. While it was costly to finance roadway construction, the result brought vast wealth to help the Romans maintain, protect, and expand their kingdom. 2,000 years after their construction, these roads are still being used to amplify their economy.