5 Strange Discoveries About Petra

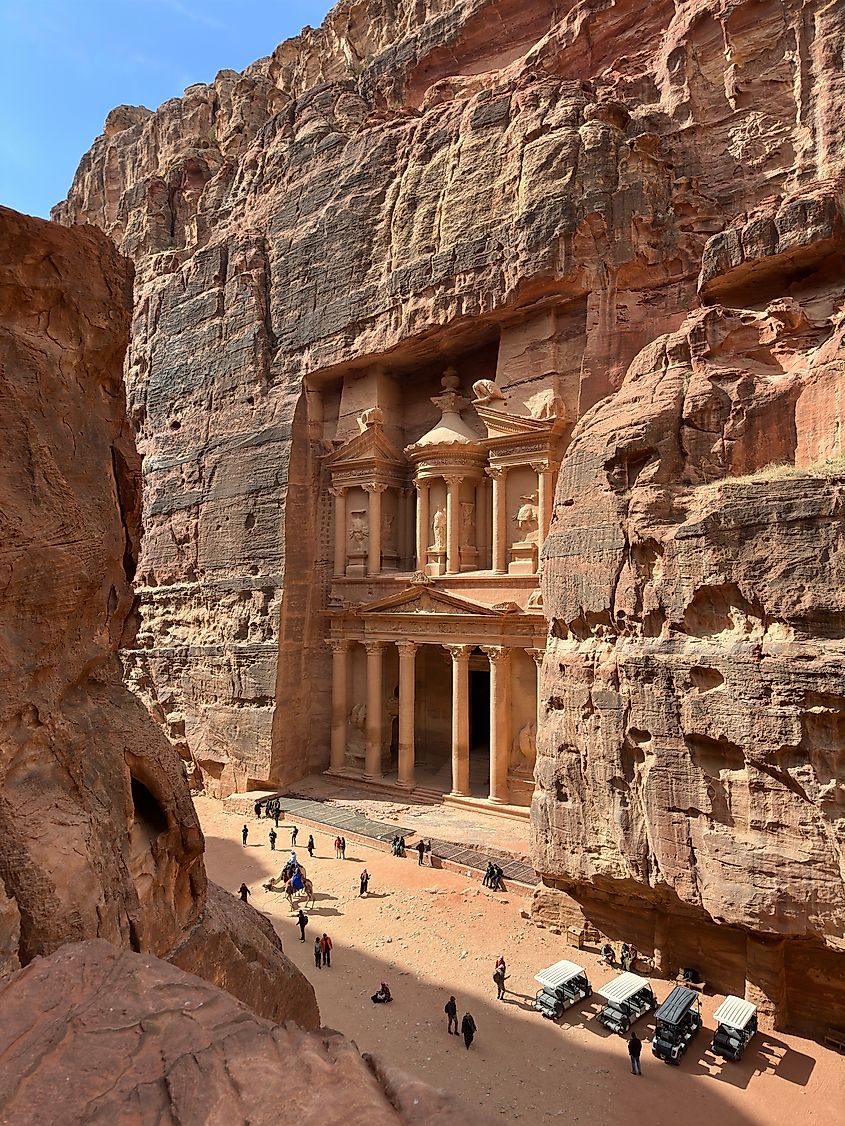

Deep in the mountains of Jordan, a red city rises out of the cliffs, built by an ancient people whose lives and beliefs remain partly hidden. Petra, once the center of an Arab kingdom, is now a two-thousand-year-old ruin and one of the world’s most important archaeological sites. A UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the Wonders of the World, Petra draws close to a million visitors each year, along with researchers from many fields. Yet even with steady excavation, much of Petra’s story is still unknown.

Flourishing around the 1st century BC, Petra declined after earthquakes and changes in trade routes. In its prime, it served as the capital of the Nabataean Arabs and later as a Roman trading center. Western interest began in 1812 when Swiss traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, disguised in local clothing, gained access to the site. Today, the city is known for its two largest monuments, the Treasury and the Monastery, but experts believe only a small portion of Petra has been excavated. As work continues, new discoveries are reshaping our understanding of ancient life in the region.

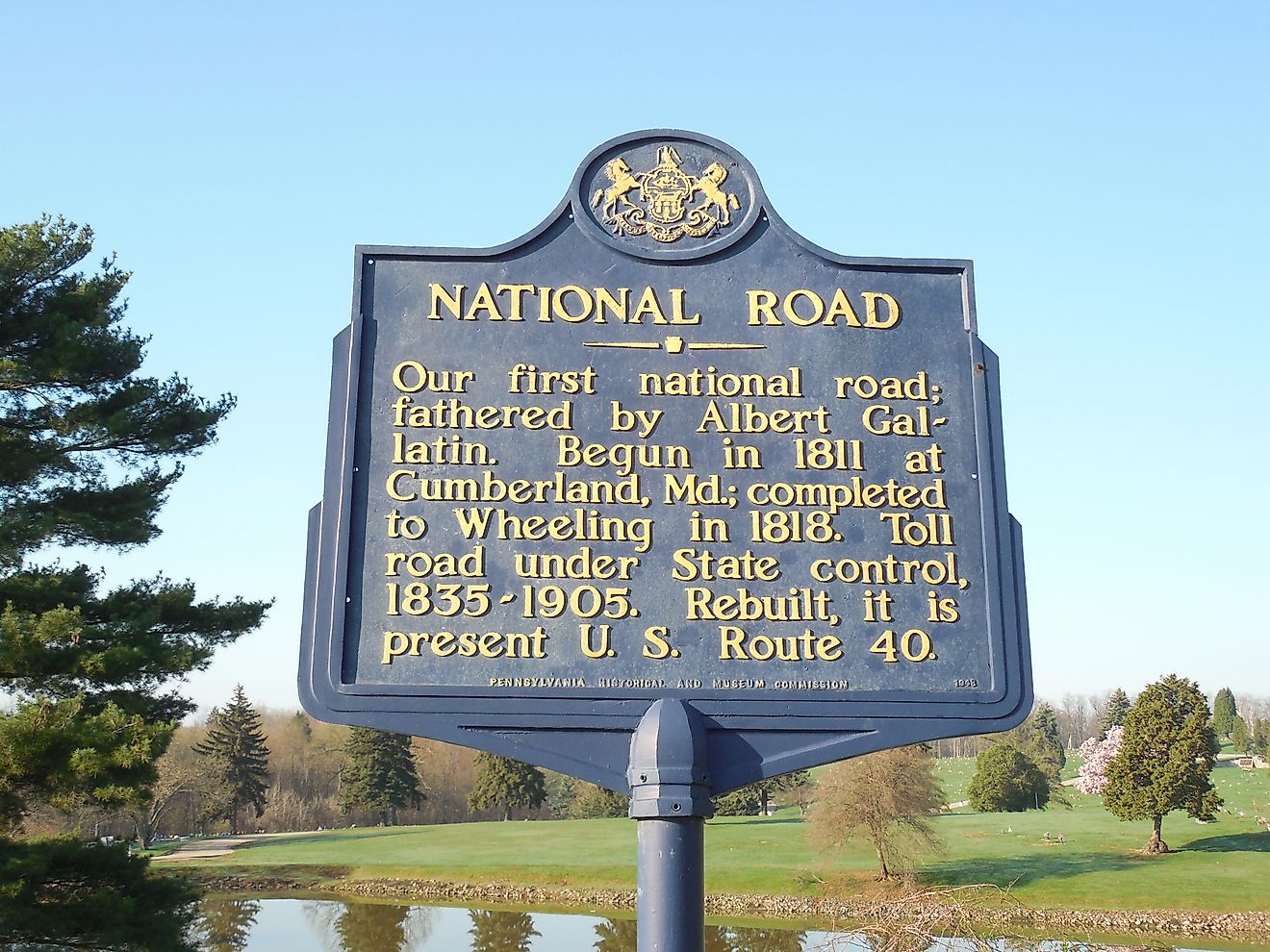

A Hidden Tomb Beneath the Treasury

Anyone familiar with Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade will recognize Petra’s Treasury, its carved façade forming the backdrop for one of the film’s most famous scenes. In a coincidence that drew global attention, archaeologists uncovered a hidden tomb beneath the structure, containing twelve skeletons and a cup that looked surprisingly similar to the film’s grail.

The discovery, reported in 2024, included bronze, ceramic, and iron objects that support the idea that the Treasury may have been a mausoleum rather than a storage site. At least twelve Nabataean burials appear connected to the monument. One skeleton held a cup whose shape closely mirrored the movie prop, though later study confirmed it was a standard vessel from the late Nabataean period. The resemblance shows how easily fiction and archaeology can cross paths in the public imagination.

A Desert Water System That Sustained a Stone City

At its height, Petra supported a population estimated to be in the tens of thousands, all living in a dry canyon with limited natural water. To support life in such conditions, the Nabataeans created a water system far ahead of its time. They carved channels, pipes, and cisterns into the rock, carrying spring water into the city through carefully managed routes. Collected water passed through settling basins and then into large storage vats with high stone walls that kept the contents cool. Since flash flooding posed a risk, they also built dams and diversion structures that guided floodwater into reservoirs. The engineering behind this system shows that the Nabataeans were skilled planners who understood their environment and developed effective solutions to survive in it.

A City Aligned With the Sun

Although separated by vast distance and time, Petra shares a surprising trait with Stonehenge and Newgrange. All three were constructed with celestial alignment in mind. In 2013, researchers studied how Petra’s sacred buildings relate to the sun. They found that many monuments were positioned to illuminate key spaces during important astronomical events, such as solstices and equinoxes. The effect is most visible at the Monastery. During the winter solstice, the setting sun aligns with the entrance, lighting the inner chamber in a controlled beam that lasts for about two weeks around the solstice. These observations suggest that the Nabataeans may have practiced a religion centered on celestial forces. The temples could also have served as seasonal markers, helping the community track time in an environment with few natural cues.

Mysterious Stone Cubes at Petra’s Edge

Three large stone blocks rise near Petra’s entrance, positioned like silent guardians. Known as Djinn Blocks, they date to around the 2nd century BC and are believed to be among the earliest monumental tombs at the site. Two contain burial chambers, while the third holds a grave on its upper surface.

Their purpose remains uncertain. The most accepted idea is that they served as tombs, but some scholars suggest that the blocks themselves may represent deities or have been used in ritual practice. Their name comes from the Arabic term for spirits. Since the Nabataeans left few written records, the meaning of the structures remains unclear.

A Roman Theater in a Nabataean Capital

While Petra contains hundreds of burial monuments, it was far more than a city of the dead. Excavations have revealed buildings that show a thriving settlement, including a large theater carved directly into the cliffs. Although its design follows Roman style, researchers date the theater to the 1st century BC, meaning the Nabataeans built it before Roman annexation. It is widely described as the only known theater carved from solid rock. It could seat around four thousand spectators before the Romans expanded it to roughly double its original size.

Secrets Beneath the Soil

Almost a century has passed since the first formal excavation of Petra, led by Agnes Conway and George Horsfield between 1928 and 1936. Yet much of the city remains untouched. Ongoing projects continue at the Great Temple, the Treasury Courtyard, and the North Ridge, among other areas. With only about twenty percent of the site excavated so far, most of Petra still lies hidden beneath sand and stone. As research advances, new findings will keep shaping our understanding of this ancient desert capital and the people who once lived there.