These 8 Towns In Texas Feel Like Home

Texas greets drivers with highway signs that read "Drive Friendly, The Texas Way." They are more than traffic reminders; they are a civics syllabus, declaring that courtesy ranks beside cattle and crude on the state’s ledger of exports. From the slot-canyon deserts west of the Pecos to the live-oak hammocks near the Louisiana border, Texans still wave through windshields, hold screen doors, and ask after your mama before learning your last name!

This article follows that signal to eight places where "home" is not a ZIP code but a reflex. Each community scores high on what sociologists call "social capital," yet locals would explain it more plainly: pot-luck algebra, fence-line trust, and Friday-night phone trees that ignite when a neighbor’s truck won’t start. These eight towns prove that Texas hospitality isn’t folklore; it is infrastructure!

Granbury

Granbury unites Victorian architecture with a shoreline that bends like a pocketknife around its courthouse square. The 1886 Granbury Opera House, gutted and rebuilt for Broadway-on-the-Brazos productions, anchors a National Register historic district where original hitching rings remain embedded in limestone curbs. Lake Granbury, a 5,980-acre Brazos impoundment, places paddleboards within three blocks of Pearl Street, integrating water recreation into civic core design seldom seen elsewhere in Texas. Seasonal hydrangea plantings frame the courthouse lawn during summer fairs.

Matinees inside the 309-seat Opera House employ digital acoustics tuned for touring Equity casts, offering productions seldom staged in rural counties. City Beach Park imports Gulf-grade sand and rents single kayaks April through September, providing a buoy-lined swim zone monitored by lifeguards. Babe’s Chicken Dinner House, operating in a converted 1917 garage, serves fried chicken, creamed corn and yeast rolls delivered by staff who tally portions on the paper tablecloth. Revolver Brewing, located five miles east on Fall Creek Highway, opens its beer garden every Saturday at noon; Blood & Honey wheat ale pairs with pickers until last call at six.

Boerne

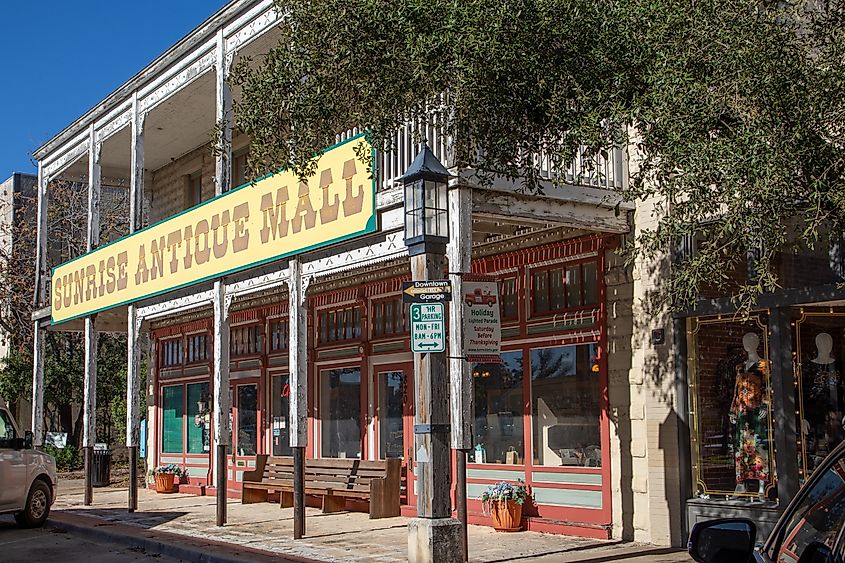

Boerne concentrates nineteenth-century limestone storefronts into the Hill Country Mile, a 1.1-mile corridor that compresses eighty owner-operated businesses without permitting franchise signage. Founder John James, a Forty-Eighter from Prussia, plotted the street in 1849; German Sunday houses and oompah music persist despite metropolitan spillover from San Antonio. The Cibolo Creek alignment floods occasionally, yet the municipal dam’s 2023 retrofit protected Main Street businesses during last year’s eight-inch deluge, underscoring resilient infrastructure.

Cave Without a Name, twelve miles northeast on Kreutzberg Road, offers tours through six chambers where soda straws and rimstone dams show calcite deposition of one centimeter every fifty years. Cibolo Nature Center maintains four ecological zones, including a boardwalk skirting a cypress swamp where Audubon chapters conduct rookery counts. The Dienger Trading Co., housed in an 1884 rock-faced commercial block, roasts Ethiopian blend for breakfast service beginning 7 a.m. and stocks goods from artisans upstairs. Corner Cartel closes the circuit with seven thousand square feet of antiques and Hill Country crafts, its barn doors sliding open until 7 p.m.

Brenham

Brenham equates to ice cream in the Texas lexicon. Blue Bell Creameries, founded in 1907, still produces two-hundred-sixteen half-gallons per minute on South Blue Bell Road and sells one-dollar scoops in a visitor parlor that hosts 200,000 tasters annually. The Chamber of Commerce’s "Tourism Friendly Texas" designation, awarded in 2022, codifies a hospitality ethos dating to the town’s days as a railroad division point.

Blue Bell’s observation deck allows visitors to watch half-gallon fillers sanitize between vanilla and cookies-n-cream runs before sampling a rotating flavor not yet in stores. One block east, Toubin Park unveils a nineteenth-century cistern system whose wrought-iron pump once supplied horse-drawn fire wagons; nightly uplighting displays the brick vault’s arch rings. The 1870 Giddings Stone Mansion, maintained by the Heritage Society, conducts monthly docent tours through four Corinthian-column porticos and eight period-furnished rooms. Evenings gather at Home Sweet Farm Biergarten on South Park Street, where twenty Texas taps accompany Friday live blues trios and a chalkboard listing regional produce vendors.

Port Aransas

Port Aransas forms the only incorporated settlement on Mustang Island, a sixteen-mile barrier guarding Corpus Christi Bay. Residents trademarked their civic ethos as "The Port A Way," a practice of unsolicited golf-cart waves that extends to ferry deckhands greeting each inbound vehicle by raised thumb. February’s Whooping Crane Festival celebrates the winter arrival of North America’s tallest bird, counting nearly six hundred individuals in 2024, an event that underwrites three coastal research grants annually.

Leonabelle Turnbull Birding Center’s 1 250-foot boardwalk penetrates cattail marsh where roseate spoonbills feed beside resident alligators identified by numbered tags. The Port Aransas Museum, housed in a relocated 1900s kit home, curates Farley Brothers tarpon skiffs and a Hurricane Harvey oral-history archive updated each September. Roberts Point Park spans fifty acres on the ship channel, its three-story observation tower providing dolphin sightings and tanker silhouettes against sunset. The Phoenix Restaurant & Bar, occupying a canal-front stilt building on North Alister, keeps the upstairs deck open until the 9 p.m. nightly ferry horn signals day’s end.

Jefferson

Jefferson preserves nineteenth-century river commerce in street grids originally mapped for side-wheeler moorings along Big Cypress Bayou. More than seventy landmark structures survive, supporting the city’s formal marketing slogan, "Bed-and-Breakfast Capital of Texas," a claim validated by sixty active permits within two square miles. The 1899 Excelsior House Hotel’s guest ledger lists Ulysses Grant and Oscar Wilde, anchoring tourism credibility beyond hyperbole. Former bayou pilots still narrate ghost lights during annual lantern tours.

Jefferson Historical Museum operates in the 1888 Federal courthouse, displaying Sam Houston correspondence and a two-story library room lined by Eastlake galleries. Adjacent Austin Street hosts Jay Gould’s railcar Atalanta; velvet drapes, walnut desks and a shower reveal opulence disdained by townspeople who once boycotted his railroad scheme. Caddo Lake State Park, fifteen minutes east, launches paddle trails through bald-cypress breaks where prothonotary warblers nest. Back downtown, Jefferson General Store’s marble counter serves Blue Bell shakes and five-cent coffee until 6 p.m., sustaining conversation beneath ceiling fans salvaged from steamboat warehouses.

Kerrville

Kerrville hosts the longest-running continuous folk-music gathering in North America, a reality that shapes its civic calendar more than any ordinance. Quiet Valley Ranch’s 18-day Kerrville Folk Festival welcomes about 33 000 campers each year, and the ensuing song-swap culture permeates local coffeehouses outside festival season. Seven miles southwest, the Museum of Western Art safeguards 150 bronzes by Russell, Remington and newer interpreters inside an adobe-style building designed by O’Neil Ford.

The museum’s galleries open at 10:00, permitting a same-day shift to Guadalupe River kayaking from the Little Pecan loop at Kerrville-Schreiner Park, where flat-water rentals trace a mile-long circuit beneath cypress branches. During festival weeks, evenings move back to Quiet Valley Ranch; main-stage sets begin at dusk while peripheral tents host workshops that once introduced Lyle Lovett and Robert Earl Keen. A five-minute drive north reaches Pint & Plow Brewing Co.; Headwaters pale ale meets brisket tacos and open-mic sessions popular with off-duty performers. These four institutions, museum, park, festival, brewery, form the cultural lattice that gives Kerrville an enduring reputation for art, recreation and uninterrupted musical dialogue.

Fredericksburg

Fredericksburg positions global history on a small-town street. Its National Museum of the Pacific War, spanning 55,000 square feet around Admiral Chester Nimitz’s family hotel, remains the nation’s only institution devoted solely to the Pacific theater and still mounts live flamethrower demonstrations during combat-zone programs. Downtown storefronts retain bilingual German-English signage, and hilltop orchards dispatch roughly three million peaches statewide each summer, preserving immigrant agriculture alongside martial memory. Monthly courthouse-square bell concerts recognize new citizens and reinforce the town’s civic cohesion.

Enchanted Rock State Natural Area rises 425 feet north of town; its pink granite dome grants sunrise vistas across the Llano Uplift and uses timed-entry reservations that protect desert quillwort colonies. Back on Main Street, Vaudeville Bistro’s limestone cellar serves duck-confit flatbread beside rotating exhibitions of Texas modernists, linking palate to palette. Fredericksburg Pie Company, open Thursday through Saturday, sells bourbon-pecan slices until the chalkboard reads “gone,” often by noon. Grape Creek on Main pours estate tempranillo and methode champenoise brut until 5:30 p.m., completing a loop that merges geology, cuisine, dessert and oenology during an easily walkable downtown circuit.

Wimberley

Wimberley anchors a limestone valley where artesian water shapes both land and identity. Jacob’s Well, a twelve-foot-wide spring plunging 140 feet into a karst chimney, feeds Cypress Creek and documents a five-millennia hydrologic pulse measured by dye-trace studies. Upstream, Blue Hole’s sapphire channel, once a summer camp, now a municipal preserve, secured National Geographic recognition among America’s top swimming spots. Commerce follows culture; Wimberley Market Days ranks second statewide for vendor count, with booth fees underwriting local scholarships.

Blue Hole Regional Park administers a timed-entry system that caps daily swimmers at 250 and preserves the cypress-shaded corridor for aquatic vegetation surveys. Jacob’s Well Natural Area issues summer snorkeling permits and guided hydrogeology tours that descend to the first chamber’s edge before oxygen monitors prohibit deeper access. The Leaning Pear, located at 111 River Road, plates roasted-poblano mac with Hill Country goat cheese and overlooks the Blanco tributary from a screened deck. Wimberley Glassworks, five miles south on Ranch Road 12, hosts narrated furnace sessions where visitors safely witness molten gathers become tumblers still warm enough to imprint fingerprints.

Across these eight communities, friendliness functions as civic infrastructure, binding Victorian squares, Gulf jetties, peach orchards and campfire song circles into one statewide neighborhood. Whether lake breezes in Granbury or Jacob’s Well springs in Wimberley, Texas proves that a warm hello and a shared story still build the strongest home.