The Great Green Wall

The Great Green Wall or the Green Wall of the Sahara and the Sahel (Grande Muraille Verte pour le Sahara et le Sahel in French) initiative is one of the most high-stake and urgent movements of our times.

The project led by the African Union aims to combat land degradation and the droughts, and remedy the famine and conflicts that follow. The great hope is to lift the lives of millions of people by restoring land productivity to the sustainable food security level across North Africa.

Here is the story of how from the paper project of the line of trees bordering the vast deserts, the vision of a Great Green Wall has evolved into the ground-level interventions implemented by the people of the Sahel and the Sahara themselves.

The Why Of The Great Green Wall

The Sahel stretches 3,360 miles from the Atlantic Ocean to the Indian Ocean. It looks like a band of the arid savannah running across the edge of the Sahara. Rainfall is low, edging 4 inches some years, and droughts are getting predictably more and more common with the climate change impact. The region is one of the poorest in entire Africa, yet the Sahel's population is expected to double by 2039, adding urgency to the food and water security concern.

Facing the insurmountable challenge of the continent-scale hunger, poverty, and unrest, scientists and economists turned to the roots, literally - to the trees, unrivaled by any artificial means in reviving the land.

The First Failed Plan

The multibillion-dollar plan to plant a 4,000-mile-long wall of trees was, ultimately, a failure. In the beginning, the project looked like a simple answer to the complex problem of the creeping desertification across Africa. Plant a wall of trees 10 miles wide and 4,350 miles long, across several countries from Senegal to Djibouti.

Why was the initial vision a failure? First and foremost, the problem was misunderstood. It had nothing to do with the desert moving southward: instead, the overuse was ruining the productivity over the entire dryland. Plus, planting trees across the Sahel never had a chance to succeed: there was no science suggesting it would work or sufficient funds to support it. Significant stretches of the planned wall were uninhabited, which meant the saplings would have no one to take care of them.

The Colonial Influences

Farmers in the Sahel were taught by the French colonists to keep clearing up the land for the crops: a technique that could work in the European ecosystem but was not adapted for Africa's one. The colonial and the following laws attempted to preserve the trees by making cutting them for fuel punishable by jail. The impact was the opposite: maintaining trees on their lands became so undesirable that the tree population began to decline severely.

Over dozens of years without the trees to protect the soil and to break up the winds, the top layer of the soil dried up and blew away. The precious rainwater would not soak into the ground and would run off instead, along with the well water level continually falling. Chris Reij, a sustainable land management expert, witnessed the crop yields were 14 times less than in the US.

The Great Green Wall 2.0: The Plan That Might Actually Work

Luckily, as the project evolved, scientists like Reij, Garrity, and others who worked on the ground taught us what the political leaders failed to understand: the change had to start with those who had the most direct connection to, access to, and impact on the exhausted land.

The scientists discovered that the farmers in Burkina Faso and Niger had found a cheap and effective way to restore the green of the Sahel. They were implementing basic water harvesting and retaining techniques, and they were protecting trees that were emerging naturally on their lands. They were replanting local species of shrub and bush.

Innovative farmers in Burkina Faso built "zai," grids of deep planting pits that enhance water infiltration and retention during the dry seasons. They surrounded fields by the stone walls to capture the runoff. In Niger, the farmer-managed natural regeneration became the heart of the Africa-adapted technique, combining the clearing of the land with maintaining a degree of the natural regrowth.

Successful Land Restoration

The regrowth mostly halted at the border with Nigeria, where there is more available water. Undeniable evidence that the success of the land restoration was about farmers changing the way they perceive and manage trees. Hundreds of thousands of farmers were implementing these pragmatic and readily available modifications, seeing the success it had brought their neighbors.

Mohamed Bakarr, the lead environmental expert for Global Environment Facility, shares how the vision of the Great Green Wall evolved from one that was only good at first sight to the practical one. "It is not necessarily a physical wall," - he said, "but rather a mosaic of land-use practices that ultimately meet the expectations of a wall."

This is how the Great Green Wall has changed from an unrealistic vision of planting a forest fence on the edge of a desert into a program centered around indigenous land use techniques developed by the farmers themselves. A program that has a chance at success is about the governments and investors empowering the ground level execution, done by local communities' efforts.

The Grassroots Efforts And The Value Of Ownership

The incredible work done by farmers in Niger means that they already have their Great Green Wall. More communities now need high-level support and empowerment to scale it up to the level of the entire continent.

The World Bank has committed $1.2 billion to the project, under the general framework of regenerating the bush and forest landscapes using the techniques that fit each country and their communities. Niger, Senegal, Burkina Faso, and Mali have advanced their initiatives much more than others. Ghana and Cameroon just began their efforts.

The work is still moving very slowly and the initiative requires a lot of support to push it forward. In order to feed the skyrocketing population, the regreening must be finished within 10 to 15 years.

The Great Green Lessons

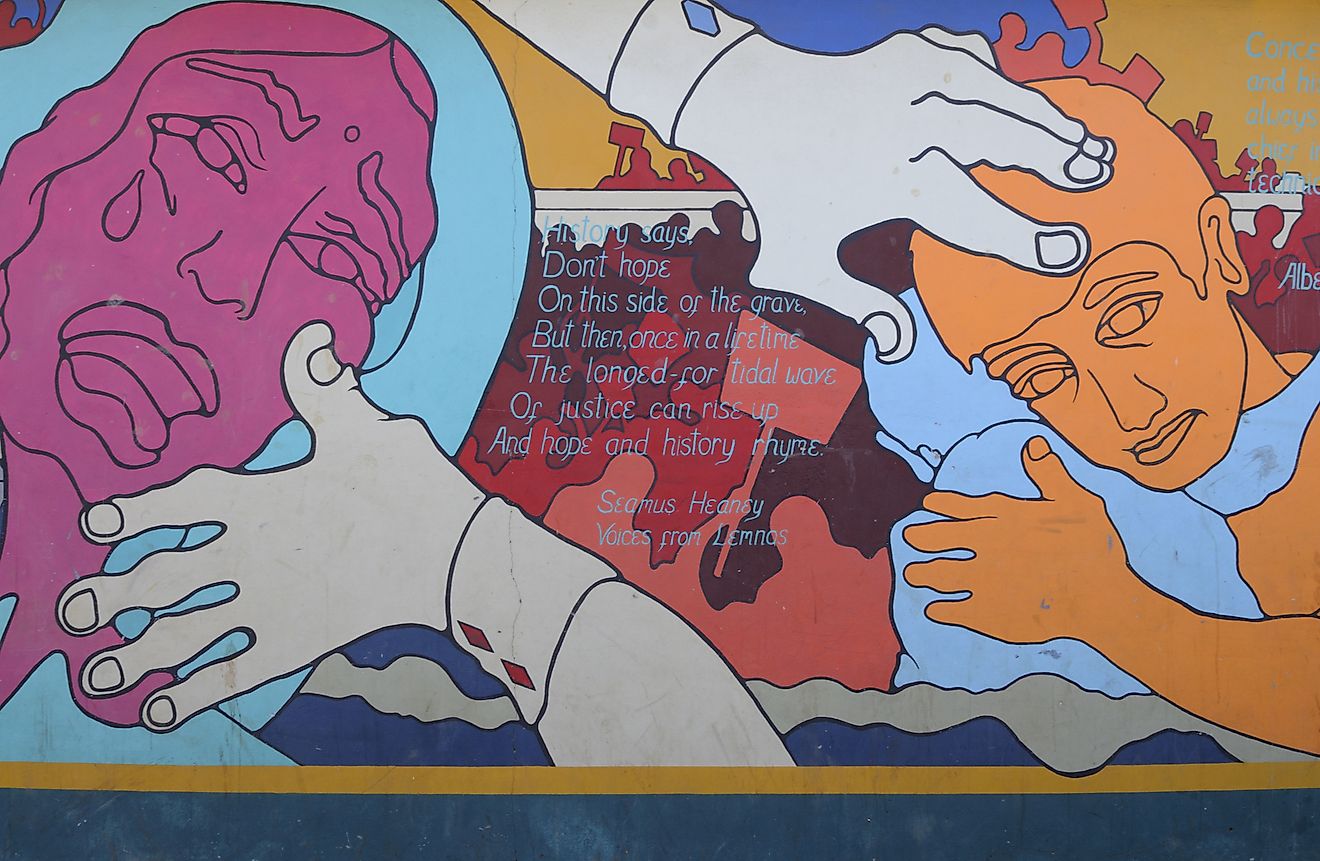

It is a humbling story in many ways. We had undermined our own future by short-sightedness: we stripped the land from its natural safeguards that could have kept us safe and fed. Leaving some space for the bushes to coexist with us on the land ended up being the only way for us to benefit from the land ourselves.

This is not the first time, either: the Great Sahara itself is a human-made desert. The long-gone generations used the naive expansive method of exploitation on what undoubtedly seemed like an endless resource. The past can't be changed. But we can use it to make better decisions in the future.