Animals That Thrive in the World's Harshest Climates

Life finds a way, no matter how hot, cold, wet, dry, or otherwise inhospitable the conditions, animals have managed to thrive in nearly every climate and ecosystem on the planet. For humans, these same places are often dangerous or difficult to navigate, whether it’s thin oxygen at high altitudes, freezing sea ice, scorching deserts, or remote volcanic slopes. In many extreme environments, wildlife and people still cross paths, sometimes in friendly curiosity, sometimes in competition for food or territory, and occasionally in conflict.

From Arctic researchers surprised by a scavenging fox, to mountaineers glimpsing a snow leopard on a sheer ridge, these encounters remind us that survival here depends on adaptation, awareness, and respect. For travelers and outdoor adventurers, understanding these animals means knowing what to expect, how to behave, and when to give them space. These six species that thrive in the harshest settings are some of the toughest survivors in the animal kingdom.

Arctic Fox (Vulpes lagopus)

Sometimes, a tough constitution does not come with a matching face, and the Arctic fox is a perfect example. Measuring between 18 and 27 inches (46-69 cm) in body length, with a tail around 12 inches (30 cm) long, and weighing from 6 to 10 pounds (2.7-4.5 kg), it may appear stuffed-animal adorable but remains one of the most resilient cold-adapted mammals in the world. Before humans settled in Iceland, the Arctic fox was the only land mammal that successfully colonized it.

As its name suggests, this species is found north of the Arctic Circle in the northernmost reaches of Europe, Asia, and North America. It navigates treeless tundra, frozen coastlines, and even winter sea ice. Living in such high latitudes means enduring temperatures that can fall to minus 58°F (minus 50°C) and finding food across challenging, often barren terrain.

Its small, compact body helps reduce heat loss, while rounded ears, a short muzzle, and thick fur covering even the pads of its feet offer vital insulation. In autumn, its coat shifts from brown or gray to a dense white layer, providing camouflage as well as warmth. Travelers and scientists working in Arctic regions often recount seeing foxes shadowing polar bears to scavenge seal remains or approaching research stations in search of scraps. They eat almost anything they can find, cleverly using the cold to store kills for later.

While they may look friendly, people exploring the Arctic are advised to keep their food secure and avoid feeding them, both for the safety of the foxes and to prevent them from becoming dependent on humans for food. It's best to keep in mind that not only is this not healthy, but the Arctic fox doesn't need the help. Everything about this small predator, from its seasonal camouflage to its ability to thrive on the move, is perfectly adapted for survival in some of the coldest places on Earth.

Bactrian Camel (Camelus bactrianus)

Camels are synonymous with the desert, but Bactrian camels have to tough out even tougher conditions than one might imagine. Rather than the baking-hot Sahara, though, these two-humped camels are native to the steppes and deserts of Central Asia — and that comes with a whole different set of struggles to survive. With their two distinctive humps, shaggy fur, and appearance of a smile, the Bactrian camel might not look like the toughest of survivors, but they have to be: their natural range spans some of the harshest climates on Earth.

From the steppes to the Gobi Desert, Bactrian camels inhabit a huge region characterized by its incredibly harsh weather. Both winter, which can see temperatures up to minus 22°F (minus 30°C), and summer, where temperatures regularly soar past 100°F (38°C), are brutal, and sandstorms are regular occurrences, too. This is the environment in which the Bactrian camel is uniquely adapted to survive.

The camel’s coat is its first line of defense. Standing 6-8 feet (1.8-2.4 m) tall and 7.5-11.5 feet (2.3-3.5 m) long, camels lose significant body heat because of their size, so a thick woolly coat insulates Bactrian camels from the cold in winter. They shed this coat in the summer to lighten the load in the hot months. They can also completely seal their nostrils, and a third eyelid helps to keep out any dust or sand that their enviable eyelashes don’t catch. But it’s not just weather that camels have to contend with: scarcity is a huge threat, too, and Bactrian camels have just as many tricks for surviving with very little food or water.

Contrary to popular belief, the humps of a Bactrian camel don’t hold water. Instead, they conserve fat, which camels can convert to energy during long periods without food. Waste excretion is optimized to conserve as much water as possible, and they’re capable of taking in huge amounts of water in a short time to store up for the dry spells wild camels often endure. When walking over burning desert sands, the wide, leathery feet of the Bactrian camel keep them from sinking and protect their feet from the heat.

It's because of these useful features that Bactrian camels have long been domesticated and used to transport people and goods in the deserts of central Asia. Thanks to their resilience and tolerance of riders when properly trained, camels have been vital to trade in the region for centuries. But did you know that those domesticated camels are actually a different species from wild populations? Though there are fewer than 1,000 wild camels left in Mongolia and China, those individuals are now thought to belong to a different species than the domestic Bactrian camel. If you happen to encounter one of these rare wild camels, keep your distance: though they look similar to the camels you might ride, they're wild animals and need their space.

Snow Petrel (Pagodroma nivea)

Picture Antarctica, and birds are probably just about the last thing that comes to mind. With the obvious exception of penguins, many believe that birds won’t thrive in such harsh climes. And this is mostly true: only three bird species have ever been found breeding at the geographic South Pole. But the little-known snow petrel is one of them.

The snow petrel's camouflage is impeccable: snow-white plumage matches its surroundings, and with a weight of merely 9.5 ounces (270 g), the diminutive snow petrel is easily missed. And the species not only ekes out a living but thrives in the Antarctic regions, living nowhere else on Earth. They breed on both the Antarctic continent and its outlying islands, a range currently thought to be the southernmost of any existing bird species. They’re able to occupy this unusual environmental niche because they subsist mostly on fish and other marine life, which is extremely abundant in the nutrient-rich waters of the Southern Ocean.

But eating all that seafood has some decided drawbacks. Too much salt tends to build up in the body, so Snow Petrels have a special gland that helps them excrete it and keep their internal chemistry balanced. And speaking of chemistry, these birds brew up something very useful: an oil in their stomachs that they can use to feed their chicks or ward off the southern skua, a predatory bird with a similar native range.

Antarctica’s utter dearth of vegetation and limited selection of land animals means that any bird that survives there needs not only to be able to tolerate the cold, but to make a living off the surrounding sea. But the Snow Petrel, perfectly adapted to do just that, is right at home. Case in point: visitors to the Antarctic regularly see flocks hanging out on icebergs. If you're exploring this most perilous of regions, you'll have to be keenly aware of the power of the elements in the coldest regions of the world -- but to the snow petrel, there's no place like home.

Snow Leopard (Panthera uncia)

There are few environments more seemingly hostile to life than the Himalayas. The world’s highest mountains have little to offer their residents but thin air, frigid temperatures, tempestuous weather patterns, and terrain that is both exceedingly treacherous and near-totally exposed. Countless human climbers have met their ends in these mountains, and the story is the same in many outlying mountain ranges of Central and South Asia. And it’s in this unforgiving place that the snow leopard reigns as undisputed apex predator.

Living on craggy mountain peaks requires immense agility, and snow leopards have that in spades. Their low-slung bodies and short, powerful hind legs make them exceptional jumpers, able to leap up to 50 feet (15 m) in a single bound, and their long tails help them maintain their balance as they navigate dicey terrain in pursuit of their prey. The mottled grey color of their coat also makes them effective hunters: from a distance, it’s almost impossible to spot them against a backdrop of snowy, rocky mountain terrain.

Cold is also a major opponent of any mountain-dwelling creature, so the snow leopard has small ears to conserve body heat. Much like the arctic fox, it can wrap its long tail around its body as a sort of blanket, and a dense coat keeps out the worst of the cold. At up to 51 inches (150 cm) long, the snow leopard's tail is nearly as long as its body, providing an excellent source of warmth.

The terrain that snow leopards call home is rightly feared by human mountaineers as a place almost totally inhospitable to human life. Indeed, the snow leopard is so rarely seen by humans that it's known as "the ghost of the mountains": not only are these cats impeccably camouflaged and increasingly rare, but they're extremely solitary and tend to avoid both humans and other animals when possible. You're highly unlikely to run into one by accident. Some companies in the region organize tours designed to give travelers the best chance of seeing a snow leopard, but not all of the trips result in a sighting!

But all of this goes to prove that the snow leopard is singularly well-adapted for its habitat. With perfect camouflage and a body built for high-altitude agility and heat conservation, the elusive snow leopard quietly haunts these foreboding mountains with skill and elegance.

Tube Worm (Riftia pachyptila)

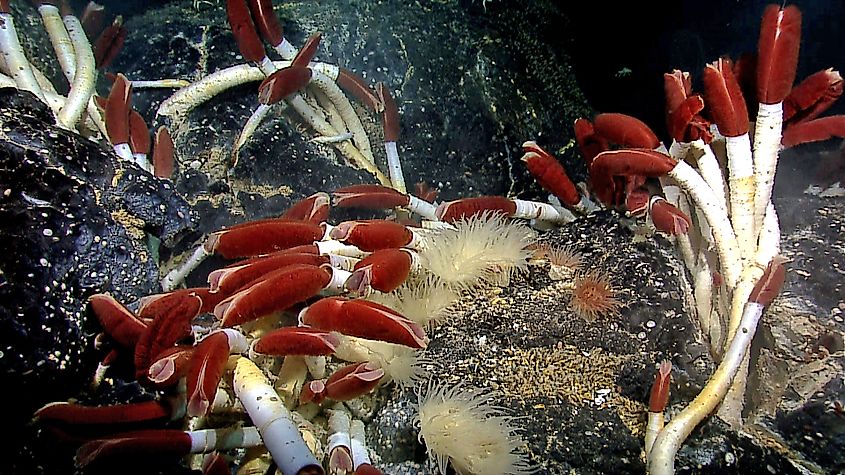

The ocean doesn’t really come to mind when talking about climate, but it does boast some of the most - if not the most - extreme conditions on earth. There are few places colder or more barren than the deep sea, where the immense pressure and lack of light keep most species nearer to the surface. But even the hostile abyss has its oases in the form of hydrothermal vents, or openings in the earth’s crust where boiling, mineral-rich water shoots up into the pitch-black abyss. These rare hotspots attract many deep-sea species, and none are more ubiquitous than the tube worm.

Tube worms are typically long, reaching an average of 7 feet (2.1 m) in length, with a thin white tube capped off by a red plume that traps particles of nutrients from the surrounding water. These sessile (non-moving) worms don’t eat or produce waste, so they attach to surfaces where they're solely sustained by the symbiotic reactions of a hydrothermal vent’s resident bacteria. It’s this relationship that allows them to thrive — they’re one of the fastest-growing animal species — in the barren depths of the sea. But that dependence on bacteria is both a blessing and a curse, because hydrothermal vents are sometimes short-lived. When the life-sustaining jet of mineral-rich water stops, tube worms almost immediately die.

However, the resourcefulness of these creatures in surviving the depths is truly remarkable. Deterred neither by cold nor pressure nor the lack of light in the deep sea, tube worms prolifically colonize any source of food they can find. When researchers send remotely-operated vehicles into the depths to look for deep-sea species, they'll almost always see the ubiquitous colony of worms protruding like so many drinking straws from the surface of a hydrothermal vent. As such, you're most likely to see these opportunistic creatures on a livestream of such an expedition or perhaps in a documentary on the deep sea.

Yellow-Rumped Leaf-Eared Mouse (Phyllotis xanthopygus)

Somewhere along the line, mice became a byword for timidity. Shy people are called “mousy”; somebody who’s hesitating might be asked if they are “a man or a mouse.” Certainly, the squeaking rodents with which we often unwillingly share our homes don’t seem too tough. But the world’s highest-dwelling rodent would like to have a word with whoever started the rumor that mice don’t have much mettle.

The Yellow-Rumped Leaf-Eared Mouse is broadly distributed in South America, and if you saw one at sea level, you might not think much. With a small, furry body and large, round ears, it looks like a mouse that a cartoonist might draw. And sure, there are plenty of places in the shadow of the Andes Mountains that experience extreme aridity, low temperatures, and fearsome storms — but that’s true in plenty of places, and rodents keep on turning out in droves.

In 2020, a group of biologists was scaling a dormant volcano on the border of Argentina and Chile. At over 22,000 feet (6,705 m) above sea level, and located on the edge of the Atacama Desert, the volcano is as dry, cold, and seemingly barren as a place on Earth could be. And in these harsh conditions, the scientists found something unbelievable: a perfectly ordinary Yellow-Rumped Leaf-Eared Mouse, squeaking out its perfectly ordinary existence in air with only 44% of the oxygen concentration you’ll find at sea level.

Although not every part of the mouse’s range demands this kind of endurance to survive, the fact that it’s been documented at a higher altitude than any other non-human mammal on the planet speaks to its ability to adapt to almost any adverse condition imaginable. Human climbers at those altitudes often need supplementary oxygen to breathe, but for reasons that researchers still don't fully understand, the Yellow-Rumped Leaf-Eared mouse's tiny lungs can get what they need from that thin air without issue. Further research will be needed to determine why this plain-looking mouse is able to withstand the stresses of that environment.

The Most Resilient Animals On Earth

There are plenty of places that seem too unpleasant for anything to survive. And it’s true that extreme temperatures, aridity, or even altitude make life a whole lot more difficult for the animals that have to reckon with them. But for every condition, there’s an adaptation, and no climate is truly so inhospitable to life that at least a few resourceful animals haven’t managed to put down roots there. They may be hiding in plain sight, but examples of the resilience of life are present in every hostile climate on Earth.