4 Historic Battles That Shaped North Dakota

North Dakota’s prairies stretch out under huge skies, and critical historical stories lie under those long blue horizons. These plains were where old battle scars were formed, long before North Dakota was even a state. Back then, the frontier still was raw and wild, with conflict that tested its people's survival and identity. Métis hunters, Dakota warriors, and United States soldiers fought in struggles remembered for their hardship and resilience. While many of its essential battles happened over a short stretch of years, their legacy lives on. Please keep reading to learn about four battles that shaped North Dakota and how they left their mark on the state.

Battle of Grand Coteau

Paul Kane's oil painting depicting a Métis buffalo hunt on the prairies of Dakota in June 1846. Photo via WikimediaCommons

In mid-July of 1851, a Red River hunting party found itself in the fight of its life. They were deep in Dakota Territory, on the edge of the Grand Coteau of the Missouri River, a stretch of high prairie lying southeast of today’s Minot, North Dakota. The group was mainly Métis families from the Red River Settlement in today’s Manitoba, led by Jean Baptiste Falcon. They had about sixty armed men among them. The rest were women, children, and the carts that carried their supplies. Scouts brought word on July 12 about a large band of Dakota. Parley was attempted but broke down. Across the prairie came a force of Yanktonai Dakota, and while exact figures vary, it was said to be in the thousands. There was no time to run. Falcon ordered the carts into a defensive ring, a tactic long used on the plains to turn a camp into a fortress. Inside, the women and older boys began loading muskets and bringing water, while the men took positions between the wheels.

At dawn the next day, the Dakota charged. The hunters held their fire until the riders were close, then answered with a crashing volley. The attackers circled, feinted, and came on again. The pattern repeated throughout the day, and again the next morning. One memory from the second day stuck with me, as during the fighting, Father Louis‑François Richer Laflèche went to every man, woman, and child during the attack to bless them and comfort them. By the afternoon of July 14, the Dakota pulled back, leaving dozens of their dead on the field. Despite this, the Métis lost only one man. The battle became legend among their people, proof that a small, prepared group could face a much larger force and walk away.

Siege of Fort Abercrombie

Sioux - Chippewa Peace Conference: Fort Abercrombie, August 12-15, 1870, Dakota Territory. The Sioux and Chippewa signed a Peace treaty that day that has never been broken. Photo via WikimediaCommons

Back in 1862, Minnesota was being torn apart by the Dakota War. Fights broke out between the Dakota Sioux and settlers after treaty promises were tossed aside. That summer, the violence moved fast, sweeping through the frontier. Fort Abercrombie, on the Red River near where Wahpeton, North Dakota, is today, became a rally point for settlers on the run. Many army troops had been sent east for the Civil War. A small garrison of the 5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry remained, commanded by Captain John Vander Horck. By early August, news reached the fort that Dakota warriors were burning farms and killing settlers nearby. Vander Horck called in his scattered men and armed every settler he could, ensuring everyone would join the fight.

A real test for the settlers began on September 3. Warriors struck the stables on the south side. Soldiers held their fire until the attackers were close, then let loose with muskets and a small howitzer. The fighting lasted hours before the attackers pulled back. A larger assault followed on September 6, this time from several sides. Defenders threw up rough barricades with barrels and dirt inside the fort, firing steadily at whatever targets they could see. Flaming arrows arced into the fort on more than one occasion. The attacking force tried to set the stables' roof on fire, but a soaking rain the night before kept the fire from spreading. By the time September wore on, the defenders were tired but still holding. On the 23rd, a column of 500 army reinforcements from Fort Snelling arrived. The Dakota force slipped away soon after, following shelling from the fort. The siege had lasted for weeks. Four defenders were dead, two wounded, but the post stood. In the following years, the army strengthened the fort with blockhouses and a stockade, but the story of that siege remained.

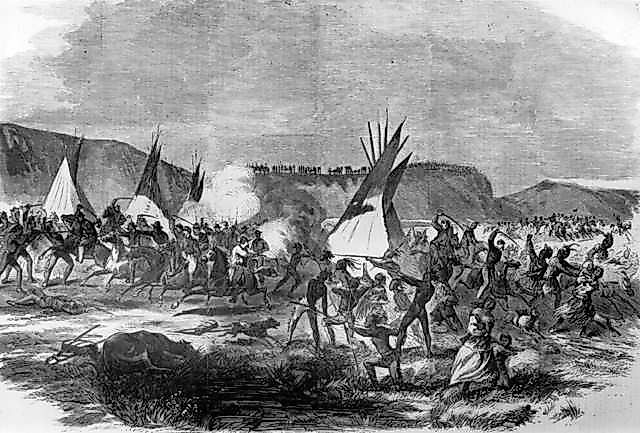

Battle (or Massacre) of Whitestone Hill

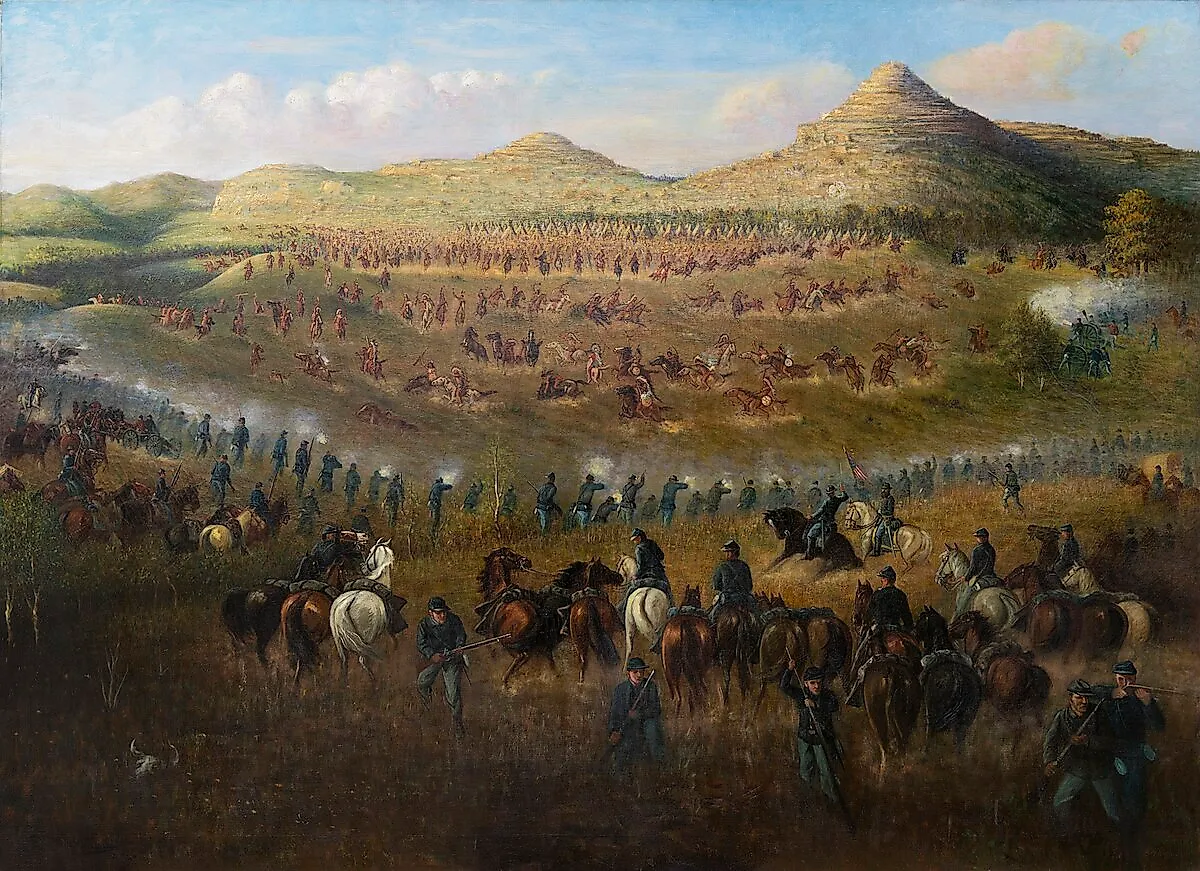

A Native American (Sioux) camp is being invaded by Sully's brigade during the Dakota Wars at the Battle of White Stone Hill, North Dakota, September 3, 1863.

In early September 1863, Brigadier General Alfred Sully led a U.S. Army expedition into Dakota Territory as part of a broader campaign following the Dakota War of 1862. Around 1,200 soldiers, his force encountered a large Native encampment near Whitestone Hill—home to hundreds of Yanktonai, Santee, Hunkpapa, and other Sioux families who had gathered for the annual buffalo hunt.

The camp was not a military target in the traditional sense. It included many women, children, and elders, and was not expecting an attack. When Sully’s scouts discovered the camp on September 3, Native leaders approached under a white flag, seeking to negotiate. However, the talks quickly broke down when Sully demanded unconditional surrender.

Fearing encirclement, many Native families attempted to flee. Sully’s troops launched a coordinated assault, surrounding the camp and cutting off escape routes. Fighting continued into the night and the following day. By the end, the U.S. Army had destroyed the entire camp—burning lodges, killing dogs, and destroying over 400,000 pounds of dried buffalo meat, which was essential for winter survival.

Estimates of Native casualties vary. U.S. military reports claimed around 100 Sioux were killed, but Native accounts and later historians suggest the number may have been closer to 300, including many non-combatants. Around 150 people were taken prisoner. U.S. casualties were reported as 20 killed and 38 wounded.

Samuel J. Brown, a civilian interpreter who witnessed the event, later described it as “a perfect massacre.” Today, many historians and Native communities view the Battle of Whitestone Hill not as a military victory, but as a tragic and disproportionate use of force against a largely non-hostile population.

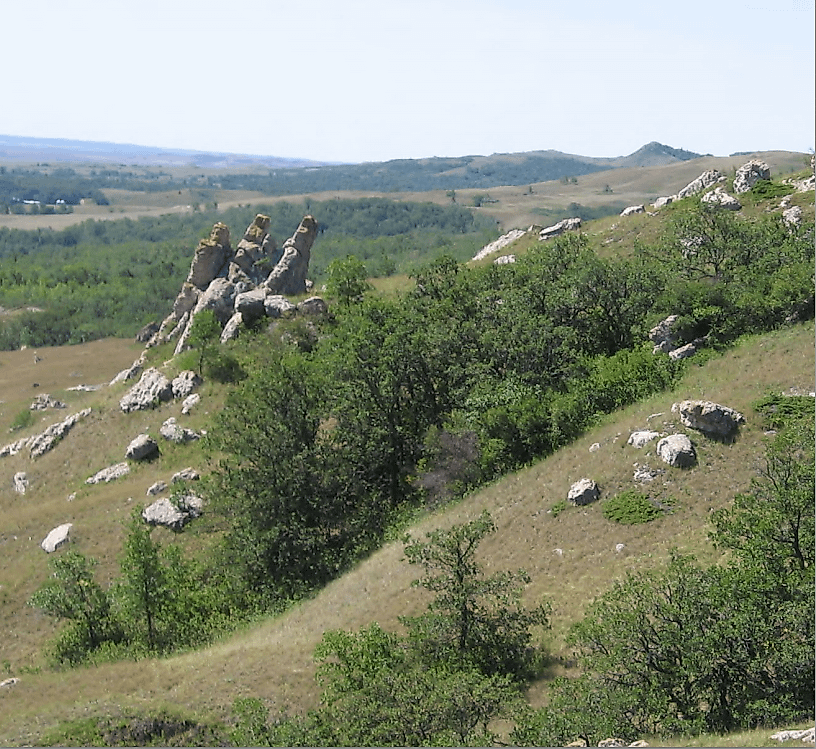

Battle of Killdeer Mountain

On July 28, 1864, Brigadier General Alfred Sully lined up his men just east of Killdeer Mountain in Dunn County. He had about 2,000 soldiers with him, most from Midwest regiments. The campaign was part of the U.S. Army action against Sioux groups after the Dakota War and the Battle of Whitestone Hill. The Army hoped to stop resistance and make it safe for settlers to head further west. Scouts reported finding a large Sioux encampment nearby. The gathering had families from the Hunkpapa and the Miniconjou groups. Some of the leaders present were Sitting Bull and Gall, with a large assembly of warriors. Estimates of how many warriors differed, ranging from about 1,600 to over 5,000. Sully advanced in a large hollow square formation with artillery in the center. The Sioux became aware of Sully’s approach through distant dust clouds rising in the distance.

Before the fighting began, a warrior identified as Lone Dog rode close to the U.S. line in a show of bravery and returned without injury. The battle opened with Sioux charges against both flanks. The soldiers used rifle fire and artillery to hold their positions. Major Brackett’s Minnesota cavalry battalion counterattacked on one flank, driving back the attackers. The fighting continued through the day and into the next morning. Everything from lodges to dried meat was left behind when the Sioux withdrew. Sully ordered these supplies destroyed and many of the dogs killed. Official army reports put Sioux losses between 100 and 150 dead. U.S. casualties were recorded as five killed and ten wounded. Survivors moved west into the Badlands, where Sully’s forces pursued them in later operations.

Many of North Dakota's most important battles took place in a relatively short period, decades before it was even a state. Due to broken treaties and shrinking land, Native American groups fought back against settler expansion in their traditional lands. Métis hunters, Dakota warriors, and United States soldiers all participated in battles fought across these grasslands, and these struggles will be long remembered for both courage and tragedy.