Is The World Running Out of Water?

Cape Town, South Africa is set to become the first city in the world to run out of water. Day Zero, the day the city will be shutting off the municipal water supply, was originally set for April 22, 2018. It has since been moved up to April 12th, then pushed back to April 16th, and pushed back again to May 11th, June 4th, and July 9th, and most recently to 2019.

Day Zero

The global water crisis has recently come into the spotlight with Cape Town, South Africa announcing the city will run out of water within the next couple months. The exact day, dubbed Day Zero, is recalculated every week based on current reservoir capacity. As of February 23rd, 2018, the cities major dams were at 24.1% capacity. At 13.5% capacity, the non-essential municipal water supply will be shut off indefinitely, with residents forced to collect a daily allowance of 6.6 gallons or 25 liters from one of the many collection points around the city.

How can the second-largest city of South Africa run completely out of water? Cape Town’s size is exactly the problem—Cape Town is the second most populated area in the country. Over the past two decades the population of Cape Town has grown by almost 80%. In the same time period, the city’s water storage increased by only 15%. With three years of low rainfall, the city’s dams are now unable to maintain demand by the current population.

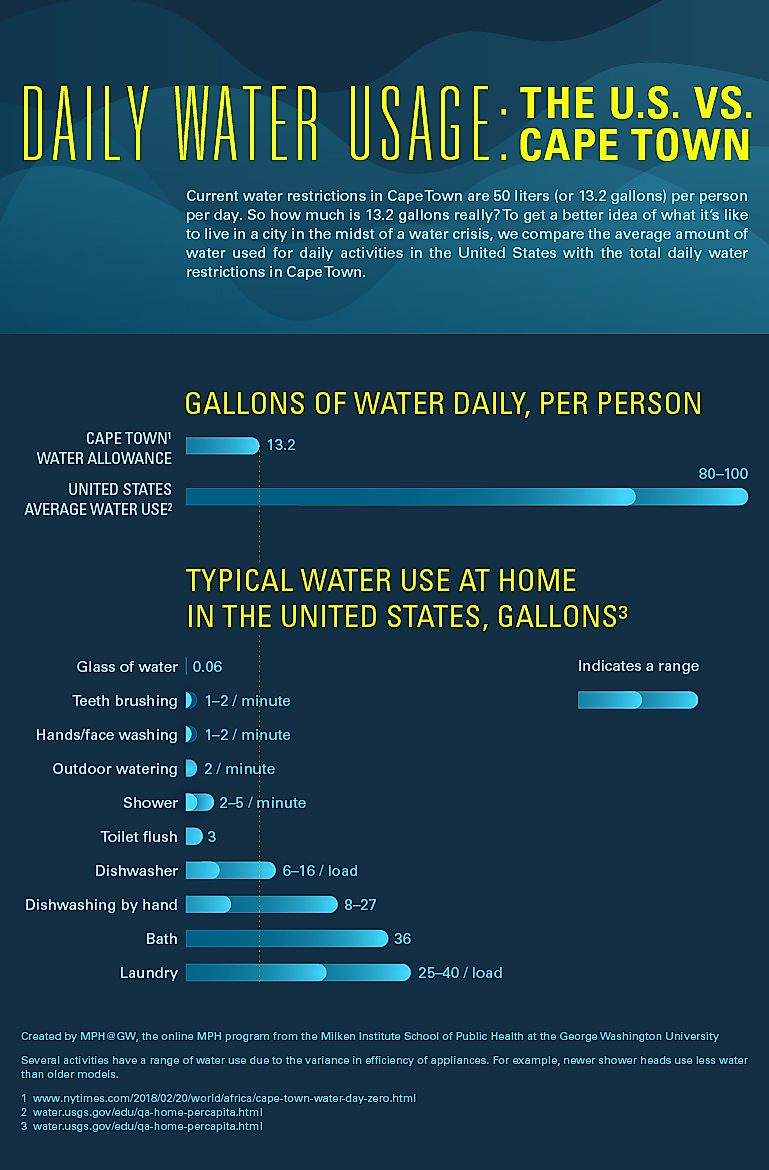

The drought began in 2015, and by May 2017 water restrictions were already put in place limiting daily water usage to 100 liters per person. In September of the same year, the restrictions tightened to a daily water consumption of 87 liters per person. In February 2018 these restrictions were once again tightened, limiting daily water usage per person to 50 liters.

Cape Town’s Theewaterskloof Dam at under 15% capacity in February 2018. Editorial credit: Michael Candelori / Shutterstock.com

Originally announced for April 22, 2018, Day Zero has since been pushed back to July 9, 2018. With rainy season expected to begin in May, combined with a water transfer into the Steenbras Dam of 10 billion liters by the Groenland Water Users' Association in early February 2018, and ongoing reductions in residential and agricultural water usage, reaching Day Zero is beginning to look less probable. The on-going threat, however, was enough to jumpstart the city and its residents into much needed action. Cape Town is now building desalination and water-recycling plants and has invested in upgrading the city’s water systems. Although Day Zero might not be realized, the scare has got everyone thinking about their water usage.

This issue is not specific to Cape Town alone. All around the globe are examples of populations experiencing what has been dubbed a water crisis.

Cape Town is encouraging residents to meet the daily water restrictions. Editorial credit: Michael Candelori / Shutterstock.com

The Global Water Crisis

The world is slowly realizing that water is a finite resource as urban centers around the globe are starting to experience water shortages. In the past several years, Mexico’s Mexico City, Brazil’s Sao Paulo, Indonesia’s Jakarta, and Australia’s Melbourne have all experienced times of water stress.

Australia’s Millenium Drought ran from 1997 to 2009, dropping Melbourne’s water levels to 25.6%. Sao Paulo’s Cantareira reservoirs dropped to 12% in October 2015 prompting daily water shut-offs throughout the city. The US state of California also experienced a significant drought between 2011 and 2017, the worst in over 1,000 years.

In all three cases, the drought ended with substantial rainfall. The crisis was averted, not ended, however. It can take years for aquifers to be replenished, and in the meantime can cause severe and devastating flooding.

Significance of Water Policies and Restrictions

With water stress becoming more frequent around the world, Cape Town more than likely won’t be the only city in this predicament. Although cities around the globe are experiencing similar times of water stress, each city reacts to this in their own way.

In the midst of the Millennium Drought, Australia began the urgent construction of desalinations plants around the country, as well as the implementation of tight water restrictions. Education program and policies encouraged residents to not only cut back their daily water usage, but also implement water recycling and rainwater capture. By the end of the drought, Melbourne residents had not only reduced their water usage by almost 50%, but a large fraction of the population had also invested in rainwater holding tanks.

During the California drought of 2011-2017, however, only a 25% residential water restriction was applied. In April 2015, the state announced mandatory water reductions in cities and towns across California, conservation rate structures by water agencies, and a rebate program for replacing older appliances with more efficient models.

Implementation of water policies and restrictions often come too late. World Atlas recently had the chance to speak with Conner Everts from the Environmental Coalition for Water Justice. Speaking about the drought in California, Mr. Everts commented that “we didn’t do mandatory conservation until the third or fourth year of long term drought, which put us at a disadvantage because we were having to catch up.”

When in the midst of a drought, cities often focus on “imposing restrictions rather than improving efficiency in water waste,” explained Mr. Everts. “It’s ongoing problem, not a temporary problem, and therefore you need to decrease usage long-term.”

One of the issues, says Mr. Everts, is after the drought: “When it finally rains, and the reservoirs begin to fill up, everyone starts to think there is enough water again, and the restrictions get lifted.” He continued, “there has to be a link between where we use the water and where water comes from.”

To put the restrictions in Cape Town into perspective, the newest water restrictions of just 50 liters per day is less than 1/6 of the average daily usage in the US and the UK, where it tops over 300 liters per person per day. With tap water not only used for drinking, but also for cooking, showering, teeth brushing, toilet flushing, dish washing, and clothes washing, the 50-liter limit is used up quickly. If the Day Zero restrictions are implemented, this will be further restricted by another 50%, with residents receiving only 25 liters of water per person per day.

Infographic by MPH@GW, the online MPH program from the Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University.

Where Does Our Water Come From?

Although 70% of our planet is composed of water, 97% of Earth’s water is salt water and 3% is freshwater. Of that 3%, only 1% is readily accessible, the remainder locked away in glaciers, icebergs, and snowcaps. This means that the population of over 7 billion people rely on the 1% of Earth’s available freshwater in rivers, lakes, streams, groundwater, and aquifers.

A recent Nasa-led study shows that 21 of the world’s 37 major aquifers are receding. Currently, however, about two billion people around the world rely on groundwater as their primary source of freshwater.

With rising populations, and with it the spread of agriculture, the demand on the world’s freshwater has increased, meaning there is less and less clean freshwater to go around. Within the next couple decades, water stress will affect more and more of the global population. This means that everyone has a role to play in the conservation of the world’s freshwater.

**

Kelly Bergevin is a writer and editor based in Montreal, Canada. She has a background in education, history, and English. She is an avid learner, reader, and coffee-drinker.