Catherine the Great's Expansion: Russian Imperial Ambitions

In the pages of history, few figures have wielded as much influence over the destiny of Russia as Catherine the Great. Catherine's ascension to power in 1762 signaled a time of remarkable change and geographical growth for Russia. Driven by a lofty dream for Russian dominance, she initiated numerous changes that influenced each spectrum of Russian society; extending from education to culture. However, in the context of modern-day Ukraine and Russian relations, it was her move to annex Crimea in 1783 that would etch her legacy.

Recognizing the strategic significance of the Crimean Peninsula, Catherine sought to secure vital access to the Black Sea, bolstering maritime trade and military might. Centuries later, these were some of the same reasons President Vladimir Putin decided to take Crimea from Ukraine. This action not only diminished the sway of the Ottoman Empire, it also fortified Russia's standing as a dominant European force. There is an enduring impact of Catherine's expansionist policies and provides a crucial backdrop to the modern-day tensions between Russia and Ukraine, where Crimea remains a focal point of contention.

Catherine the Great: A Visionary Leader

In 1762, Catherine the Great ascended to power by dethroning her husband, Peter III, an unwelcome ruler despised largely among Russia's nobility. When she was only 16, she tied the knot with the Prince of Prussia. However, soon after his ascension to power, her strategic plan unfolded. In a series of moves worthy of Game of Thrones, she gained support from both the military and political elite, ultimately ascending to the throne as Empress of Russia. With the guards pledging allegiance to Catherine, Peter III was removed from the throne. Less than two weeks later, Peter III died under mysterious circumstances.

Catherine had a grand vision for Russia, while at the same time keeping her ear close to the cultural movements of Europe. She was heavily influenced by Enlightenment ideas during her reign. The Enlightenment, spanning the 17th to 19th centuries, was an intellectual and philosophical movement emphasizing reason, individualism, and skepticism towards traditional doctrines. It advocated the scientific method, challenged religious and monarchic authority, and influenced modern political and social thought. Throughout her reign, she corresponded with several Enlightenment philosophers and intellectuals, and she even considered herself an enlightened monarch. According to historian Serhii Plokhy in his book Lost Kingdom: The Question For Empire and the Making of the Russian Nation, the Enlightenment theories changed Russia's view from a collection of territories to a more centralized state.

Catherine's vision was to have Russia more aligned with the cultural and economic patterns of Europe. She intended to create a state with more authority over its empire's territories. Her economic changes encompassed initiating industries such as textiles and mining under governmental regulation. She introduced trade privileges to attract foreign merchants and modernized agricultural practices through initiatives like the “Charter to the Nobility.” Culturally, she founded the Hermitage Museum and supported Enlightenment thinkers, helping Russia's intellectual environment grow. These policies aimed to stimulate economic growth and make Russia a bigger cultural global player.

While these were her long-term accomplishments, Catherine’s authority was challenged almost immediately after taking the throne. In 1764, the Hetmanate started to make demands on how their office should be handed down to the next in line. The Hetmanate refers to the Cossack Hetmanate, a semi-autonomous Cossack state in the region that is now Ukraine. Over the last decades and centuries, the power of the Hetmanate inside Russia had slowly eroded. Her answer to their demands came fast. In response to these demands, Catherine abolished the Hetmanate's autonomy and incorporated it directly into the Russian Empire as part of her efforts to centralize power. This decision led to discontent among the Cossacks, as well as Ukrainians over the years, who had seen the Cossacks and Russians as equals. So, instead of choosing force, Catherine worked to extend her power through bureaucratic and political means. This was shown again after her "Toleration of All Faiths" edict, issued in 1773, promoting religious freedom and tolerance within the Russian Empire.

Despite her willingness to not use force against her subjects, she was comfortable using it against her neighbors to expand her empire. Notably, she waged successful wars against the Ottoman Empire, which would lead to Russia securing Crimea and parts of the Northern Black Sea coast. Catherine also annexed territories in Eastern Europe, including parts of Poland, further consolidating Russian influence. Her policies extended to strategic marriages, like her grandson's betrothal to a Prussian princess, aligning Russia with powerful European allies.

War of the Bar Confederation

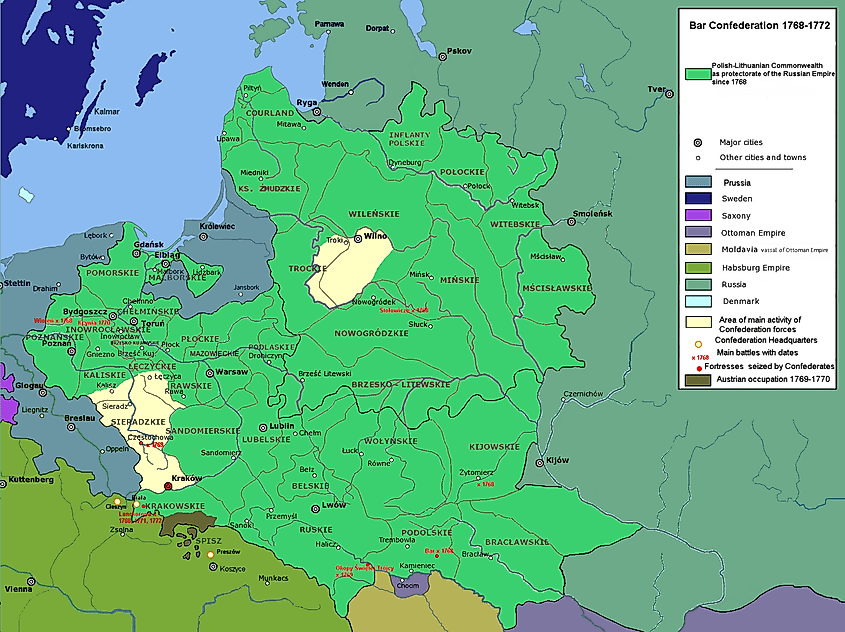

The War of the Bar Confederation was not a grand conflict in the greater scope of European history, but its conclusion helped contribute to future Ukrainians being split up between multiple empires. Catherine had her eyes on the Balkan territories of the Ottoman Empire, but she was forced to be sidetracked and focus on her neighbor to the west. In the 1760s, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth’s influence and authority in the region was waning. When its ruler Augustus III died in 1763, Catherine saw her chance to extend her influence.

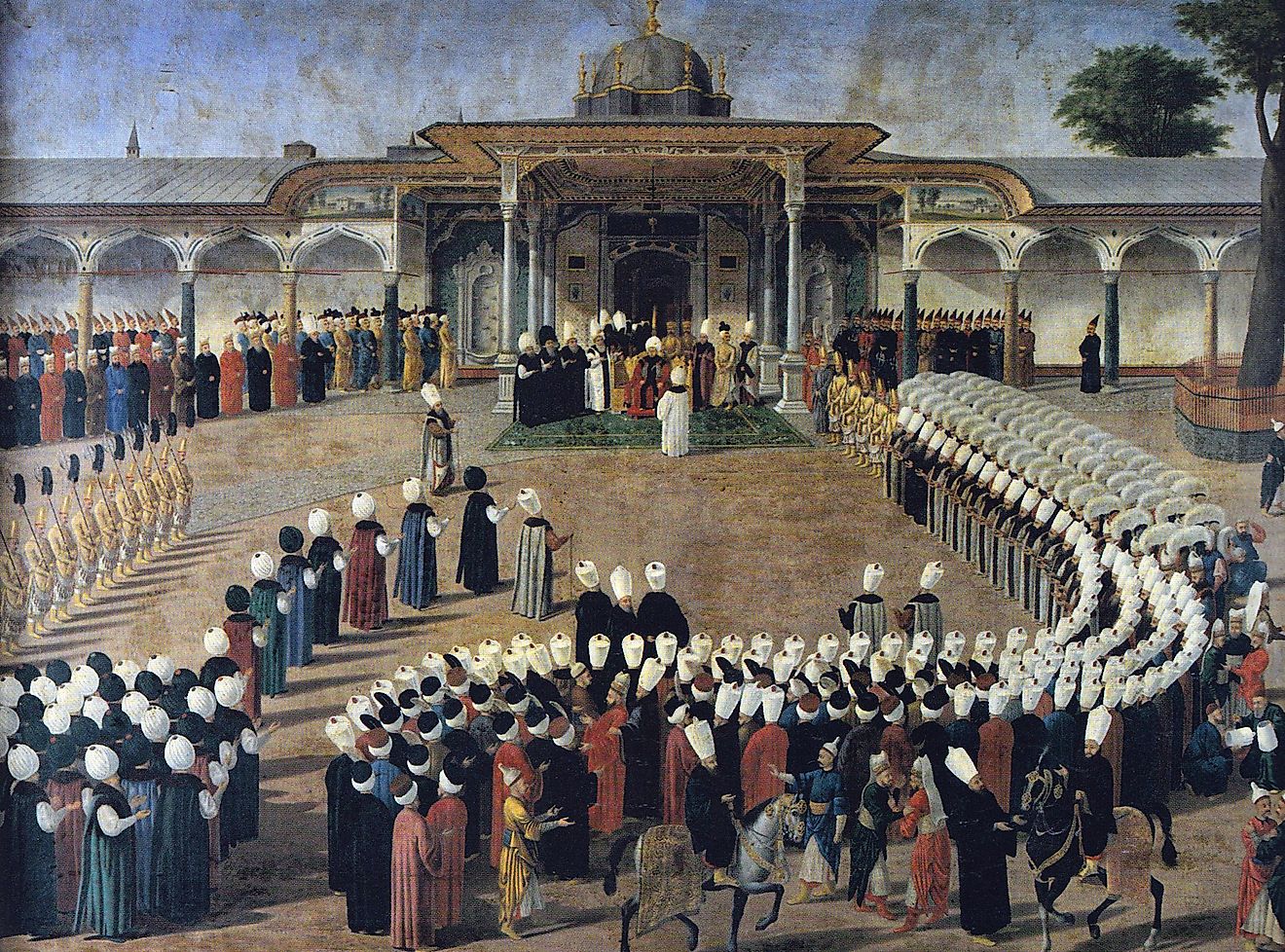

Catherine and Russia were trying to find ways to push their influence, considering how the Commonwealth had begun to weaken. Using both influence and troops, Russia helped get Stanislas Poniatowski to the Polish throne, a man who was allegedly Catherine’s lover. Despite their relationship, conflict between the two grew quickly. Poniatowski wanted to make reforms to solidify his power, moves both the Polish nobles and Catherine were against. She pressed for the rights of non-Catholics in Poland and, with an increased military presence, fundamentally made Poland a Russian protectorate.

This directly led to a Catholic revolt in 1768, known as the Confederation of Bar, a rebellion fighting against the policies of foreign influence and religious discrimination in Poland. It aimed to defend the traditional rights and privileges of the nobility against both Russian and domestic interference. The Confederation of Bar was part of a broader struggle in Eastern Europe, involving Russia, Poland, the Ottoman Empire, and Austria. Austria saw the Confederation as a means to indirectly counterbalance Russian influence. As the conflict escalated, Austria provided political and logistical support to the Confederation, using it as a tool to limit Russian expansion in the region.

The confederation gained support from the French, and uprisings began around Poland in some of its biggest cities. More importantly, the Ottoman Empire was starting to get uncomfortable at the idea of Russia pushing into the south of Poland, which bordered the edges of their empire. Like Austria, the Ottomans, seeking to weaken Russia's influence in Eastern Europe, saw an opportunity to support the confederation to create a regional counterbalance to Russian power.

Things got a lot more complicated when Cossack soldiers under Russian rule started to raid Ottoman lands in the summer of 1768. In response, the Ottomans declared war on Russia. Catherine's desire for expansion into the Ottoman lands could come to fruition. The events surrounding the War of the Bar Confederation and the subsequent treaties had long-lasting effects on the political and territorial landscape of Eastern Europe. The war ended with the Confederates' defeat, weakening an already declining Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and contributing to its eventual partition in the late 18th century. This we will come back to.

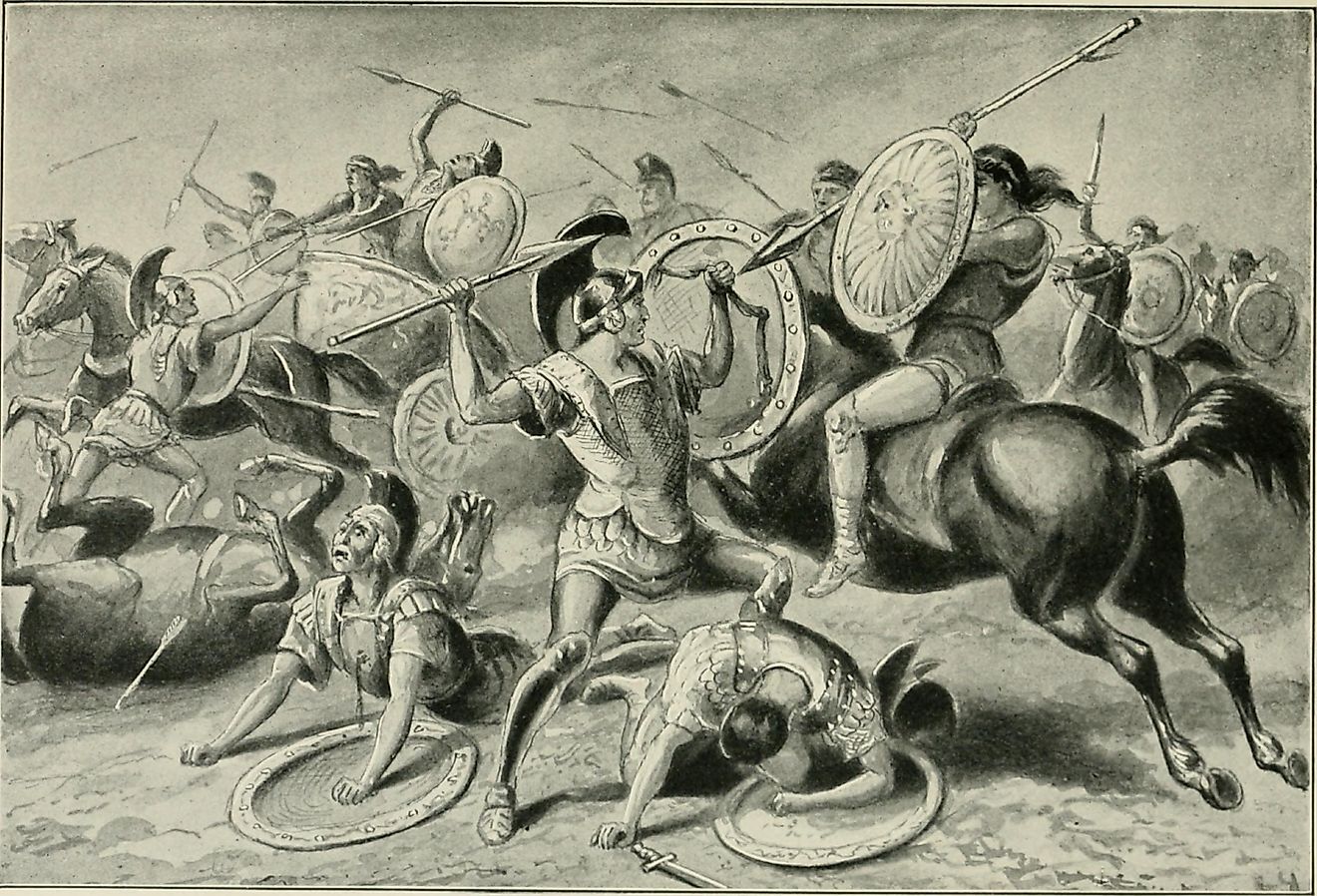

Treaty of Küçük-Kaynarca and Crimea Annexation

While the first year of the war between Russia and the Ottomans was uneventful, Catherine and her empire quickly made progress. The success continued into the next year as the army under General Petr Rumiantsev scored victory after victory. It only got worse for the Ottomans after a devasting naval loss in the Chios Strait. As more Russian victories continued, it was not long until the entire Crimea was occupied. After a series of Ottoman defeats, and as the Ottoman’s resources dwindled, a peace treaty was signed.

The Treaty of Küçük-Kaynarca ended the war and fundamentally changed the future of Europe. As part of the deal, the Ottoman Empire recognized the independence of the Crimean Khanate from the Ottomans and agreed to cease any support for the Crimean Tatars, who had been raiding Russian territories for years.

This led to the region losing its protection, thereby paving a path for Russian influence to trickle in. Russia took over the strategic stronghold of Azov along with its neighboring lands, opening a gateway for them to both the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. To relate it in present-day terms concerning the Ukraine-Russia conflict, Azov is only 125 miles eastward from Mariupol, a starkly disputed city in the war.

Something very important to Catherine was that Russia should gain the right to navigate freely in the Black Sea and to conduct trade in the Ottoman ports. The period between 1774 and 1783 witnessed ongoing tensions between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, exacerbated by persistent Crimean Tatar raids into Russian territories. Grigory Potemkin, a trusted advisor and military commander, pushed for the annex of Crimea, as he recognized the region's potential as a buffer against potential Ottoman incursions and to strengthen Russia's southern frontier in the Black Sea region. In a letter to Catherine, he says while the conquest will not make Russia stronger, it would bring peace.

Catherine, driven by ambitions for territorial expansion and bolstering Russia's influence, ultimately agreed, and decided to annex Crimea in 1783. She formalized the annexation of Crimea, significantly expanding the Russian Empire. The annexation was met with resistance from both the Ottoman Empire and local Crimean Tatars. However, Russian control was consolidated, leading to significant changes in the region. Crimea was integrated as part of the Russian Empire, with the introduction of Russian governance, language, and institutions. Securing pivotal sea routes this action did more than just that, it reshaped the demographic and political terrain prevalent in the region. Its influence is so profound its echoes are still present today.

The Dismantling of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The collapse of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth resulted in enduring impacts on Russia's overall ethnic composition. Slowly but surely, the dominions around the commonwealth began to nibble at its boundaries. Constant conflicts and inner conflict had left the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth weak against foreign entities, which had begun to divide and take land belonging to Poland. These neighboring powers—Russia, Prussia, and Austria—exploited the weaknesses of Poland and started to divide Polish territory among themselves. By 1794, large parts of Poland had been annexed.

The combined forces of Russia, Prussia, and Austria were more powerful and better equipped. The uprising was eventually suppressed, leading to further partitions of Polish territory. After this partition, the Russian Empire now possessed lands full of Ukrainian citizens. According to Serhii Plokhy, the share of ethnic Ukrainians in the empire went from 13 to 22 percent, while the level of ethnic Russians fell from 70 to 50 percent. Russia was not the only empire to absorb a large number of Ukrainian citizens. Austria would absorb the lands of Galicia, one of the historic homelands of the Ukrainian people. It would be almost 200 years until these Ukrainian people were under one nation.

Key Takeaways

Catherine the Great's territorial ambitions, particularly her annexation of Crimea in 1783, left a mark on the modern-day relationship between Ukraine and Russia. It also significantly altered the demographic and political landscape, shaping Crimea's identity as a multi-ethnic territory. While outside the scope of this article, Russia would, one day, gift Crimea to Ukraine as a move of friendship between the two Soviet Union states.

Fast forward to the present conflict, the 2014 annexation of Crimea by Russia under President Vladimir Putin mirrored Catherine's historical maneuver, this time causing international outcry and condemnation. The move violated Ukraine's territorial integrity and sparked the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War. The annexation exacerbated historical tensions, fueling nationalistic sentiments and geopolitical rivalries. Crimea remains a contentious issue, with Russia maintaining control and Ukraine fighting for its return.

The situation underscores the enduring impact of Catherine's annexation on regional dynamics and exemplifies how historical decisions can affect events centuries later.

Works Cited:

Anderson, M. S. “The Great Powers and the Russian Annexation of the Crimea, 1783-4.” The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 37, no. 88, 1958, pp. 17–41. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4205010. Accessed 4 Nov. 2023.

Charques, R.D. Between East and West: The Origins of Modern Russia: 862 - 1953. Pegasus Books, 1956.

Fisher, Alan W. “Enlightened Despotism and Islam Under Catherine II.” Slavic Review, vol. 27, no. 4, 1968, pp. 542–53. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2494437.

Griffiths, David M. “Catherine II Discovers the Crimea.” Jahrbücher Für Geschichte Osteuropas 56, no. 3 (2008): 339–48. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41052102.

Hosking, Geoffrey. Russian History: A Very Short Introduction. 1st ed., Oxford University Press, 2012.

Jaques, Susan. The Empress of Art: Catherine The Great and the Transformation of Russia. Pegasus Books, 2016.

Kasekamp, Andres. A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave MacMillan, 2010.

Mclean, Paul D. “Patrimonialism, Elite Networks, and Reform in Late-Eighteenth-Century Poland.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 636, 2011, pp. 88–110. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41328553.

Okenfuss, Max J. “Catherine II’s Restored Image, and The Russian Economy in the Age of Catherine the Great.” Jahrbücher Für Geschichte Osteuropas, vol. 45, no. 4, 1997, pp. 521–25. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41049995.

Ross, Danielle. “Review.” Mediterranean Studies, vol. 26, no. 1, 2018, pp. 128–30. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5325/mediterraneanstu.26.1.0128.

Plokhy, Serhii. Lost Kingdom: The Question For Empire and the Making of the Russian Nation. 1st ed., Basic Books, 2017.

Schönle, Andreas. “Garden of the Empire: Catherine’s Appropriation of the Crimea.” Slavic Review 60, no. 1 (2001): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/2697641.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 'Confederation of Bar.' Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/topic/Confederation-of-Bar.