The Pennsylvania Town That Won't Stop Burning

What happens when a town’s past won’t stop burning, literally? Imagine streets that lead nowhere, mail that no longer comes, and a handful of neighbors who refused to leave. How did Centralia, Pennsylvania, go from a busy coal borough to a near-ghost town with smoke seeping from the ground? Some stayed, some left, and a fire that started in 1962 still burns to this day and has shaped the landscape of the town.

Mining

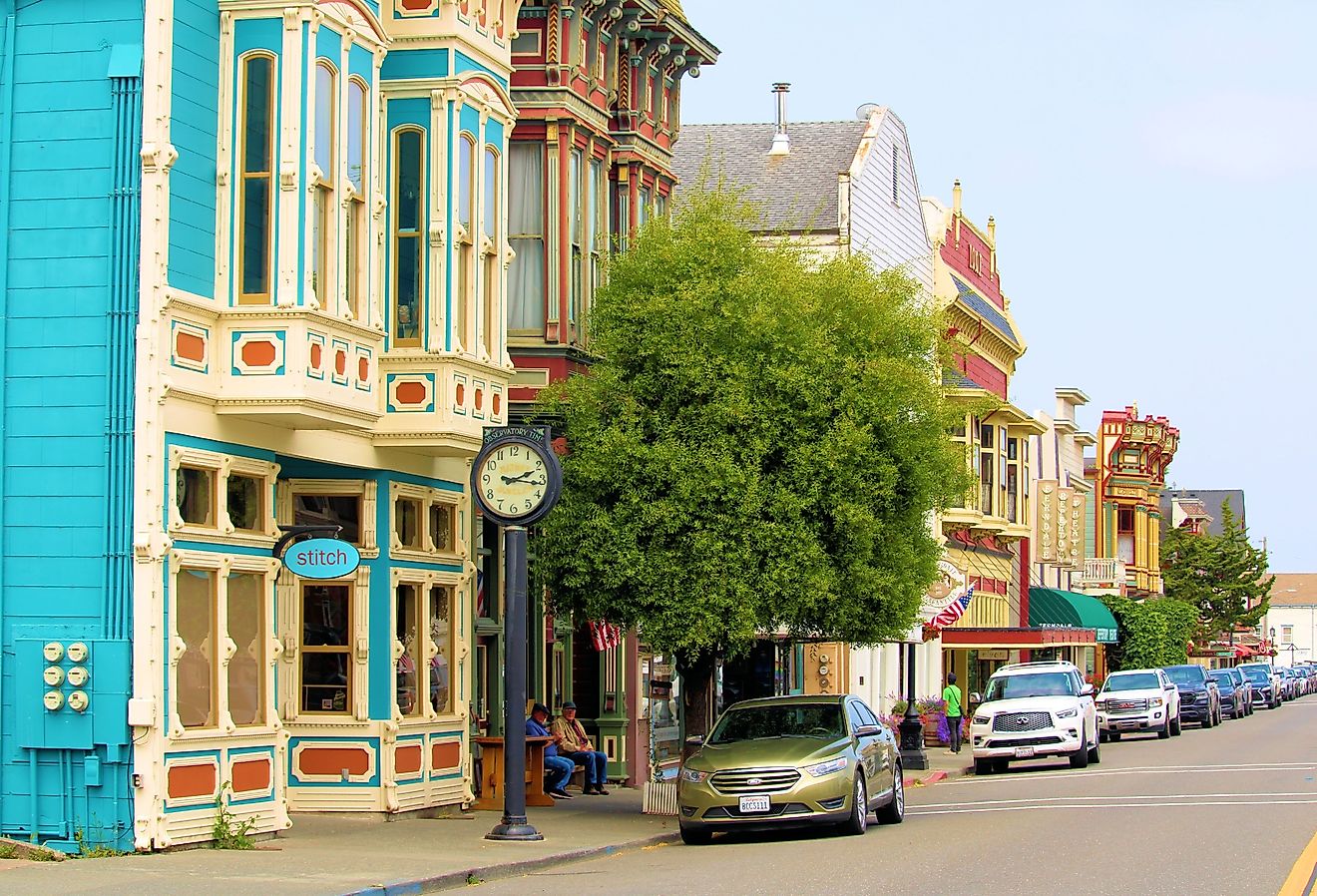

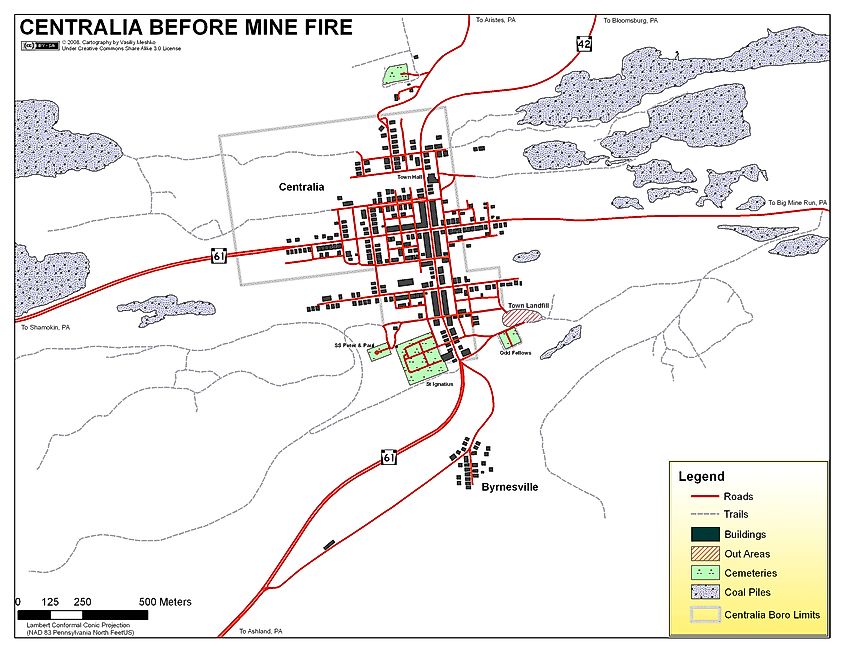

Centralia began with coal and ambition. In the 1800s, anthracite seams drew settlers to Columbia County, and a tavern called Bull’s Head became the seed of a town. A mining engineer laid out streets, railroads arrived to haul coal east, and the settlement cycled through names, Bull’s Head, Centreville, and finally Centralia, while keeping the same heartbeat: coal. By 1890, the borough’s population reached roughly 2,761. For a compact place, Centralia had outsized amenities: seven churches, two theaters, a bank, five hotels, 27 saloons, and rows of shops that served shift workers and their families.

Prosperity had a volatile edge. The 1860s and 1870s brought violent labor conflict across the Anthracite Region; Centralia’s founder, Alexander Rae, was murdered in 1868 in an incident often linked to the era’s turmoil around the Molly Maguires. Whatever the precise motives, the episode captured the tension of a coal economy where wages, safety, and power were contested underground.

Through the early 20th century, the arc bent downward. Anthracite production waned, the Great Depression shuttered major collieries, and "bootleg" miners re-entered idle workings to pry out remaining coal, sometimes by perilous pillar-robbing that hollowed support structures. Those Swiss-cheese voids would later frustrate any clean attempt to seal off a creeping subterranean blaze. Rail service ended in 1966, yet mid-century Centralia still looked and felt like a normal Pennsylvania town, schools, parishes, routines, even as the industry that built it thinned.

Mine Fire

The spark came in 1962. Accounts differ: some say a routine pre-Memorial Day landfill burn wasn’t fully extinguished; others recall hot ash from a coal burner dumped into the refuse pit. Either way, heat found unsealed openings in an abandoned strip mine near the Odd Fellows Cemetery and slipped into the anthracite seams beneath town. Subsurface fires move like slow animals: following oxygen, exploiting fissures, generating invisible gases. Centralia’s old, interconnected workings acted as a maze of bellows and conduits.

At first, danger was debated more than seen. Steam vented in cold weather; a sulfur tang drifted from cracks. Engineers tried trenches, grout seals, and excavations, but decades of undocumented tunnels and voids undermined every plan. Then came moments that no one could ignore. In 1979, the mayor, who ran a gas station, measured the fuel in an underground tank at 172°F (77.8°C).

In February 1981, 12-year-old Todd Domboski fell into a sudden sinkhole in his grandmother’s yard, a four-foot opening that plunged dozens of feet deep, venting carbon-monoxide-rich steam. He survived by grabbing a root and being hauled out by his cousin. The headline image, a child nearly swallowed by the earth, turned a local engineering problem into a national public-safety crisis.

Coal-seam fires don’t lend themselves to neat victories. To smother Centralia would have required massive excavation and sealing, with no guarantee of success. By the early 1980s, the fire had spread beneath hundreds of acres on multiple fronts. State and federal officials faced a wrenching choice: keep spending to chase an underground blaze with uncertain odds, or help people move away from a hazard that could vent, crack, or subside without warning.

Abandonment

In 1983, Congress funded a relocation program. One household at a time, a community unraveled: more than a thousand people moved, and hundreds of structures came down. By 1990, only a few dozen residents remained. In 1992, Pennsylvania condemned the borough’s remaining properties via eminent domain, and in 2002, the Postal Service discontinued Centralia’s ZIP code. The fire’s reach forced the abandonment of nearby Byrnesville as well.

Not everyone left. A small group fought eviction through the 2000s, insisting parts of town were stable and that home was still home. Courts rejected efforts to overturn the takings, but in 2013, the state and the remaining residents reached a compromise: they could remain for life, and upon each death, the property would pass to the Commonwealth. On the ground, warning signs multiplied: "Underground Fire," "Unstable Ground," and "Carbon Monoxide." The municipal grid thinned to long sightlines and grassy lots.

Another symbol of abandonment was the highway. Heat and subsidence fractured Pennsylvania Route 61 again and again, prompting a permanent reroute in the early 1990s. The stranded strip of asphalt became the notorious "Graffiti Highway," a magnet for trespassers and selfies, until the owners covered it with earth in 2020 to discourage visitors. Elsewhere, the landscape changed in quieter ways: snow melting early on warm patches, saplings pushing through cracks, foundations and steps leading to nothing.

Even amid loss, pieces of civic life persisted. The municipal building stands; volunteers organize cleanup days to curb illegal dumping; and small restoration efforts, such as planting trees, add greenery back to open lots. The message isn’t that Centralia will "come back" as it was, but that places can retain meaning even after their original purpose is gone.

How Is Centralia Doing Today?

By the 2020 census, five residents remained. Day-to-day life for the few who remain is quiet and cautious, shaped by posted warnings and long familiarity with the place’s quirks.

The fire still burns, and absent extraordinary intervention, it may do so for many decades. That long timeline reframes what "doing" means here. Centralia is no longer a town measured by new housing permits or school enrollments; it is a place defined by geology, memory, and stewardship.

Culturally, Centralia looms large. It has inspired documentaries, novels, and eerie internet lore, often blurring fact and myth. Comparisons to other disaster towns or fictional hellscapes can flatten what is, at bottom, a specific human story: a community built on a resource that later turned against it, complicated by engineering limits and policy tradeoffs.