10 Main Streets Where Ohio Comes Alive

Ohio’s best stories run straight down a centerline, where courthouse clocks keep time, railroad whistles cut conversations, and storefront signs still bear the names that built them. Main Street is the state’s seismograph: fires, floods, immigration, industry, reinvention, they all register block by block.

This list follows a simple stress test: visit at 5:17 p.m. on a weekday and see if the street is working. Are lights on in upper floors? Do delivery trucks still idle at the curb? Is there a museum, a theater, a diner, and a park within a five-minute walk? The ten that made the cut pass that test with evidence to spare, historic hotels still booking rooms, century-old halls staging shows, farmers markets that shut down traffic, and trails or riverfronts that meet the sidewalk.

Granville

Granville is an intentional echo of New England, a rarity in Ohio. Settled in 1805 by transplanted Connecticut families, it was laid out with symmetry, a central thoroughfare, and stone churches that still define the skyline. Broadway, its main street, runs straight through the heart of the village, wide, walkable, and lined with Greek Revival facades that haven’t bowed to time or trend. The town’s geography is distinct too: Denison University sits elevated just east of the strip, its hilltop chapel visible from below like a crown.

On Broadway, the Buxton Inn has been operating since 1812. Guests and passersby claim sightings of the inn’s famously polite ghosts. Across the street, the Robbins Hunter Museum displays 19th-century antiques inside a 1842 Greek Revival mansion. Further down, Whit’s Frozen Custard serves Ohio-made classics with a line out the door on warm evenings. And on Saturdays, the Granville Farmers Market fills the street with local vendors under the shade of old maples, selling fresh bread, sunflowers, and kettle corn, often to the tune of a bluegrass trio.

Chagrin Falls

Chagrin Falls is one of the only towns in Ohio built around a natural waterfall that still cuts through its downtown. The Chagrin River splits Main Street in two, with the falls visible from the sidewalk, the hardware store, and the back patio of a candy shop. Incorporated in 1844, the village developed around the power of this cascade, which once drove mill wheels and now anchors a preserved commercial core. The falls aren’t ornamental, they shape the town’s layout, commerce, and soundscape.

Main Street rises on either side of the river. On the west bank, the Popcorn Shop keeps its doors open to the mist and sells bags of caramel corn beside antique peanut jars. Across the bridge, Chagrin Falls Township Hall, built in 1848, still hosts community performances in its upper hall. Down the block, the Chagrin Falls Historical Society and Museum displays rotating exhibits like “Mid-Century Chagrin” and preserves the town’s canal-era documents. Just uphill, Jeni’s Splendid Ice Creams operates out of a repurposed bank building, often with a line curled around the sidewalk. Triangle Park at the intersection of Main and Franklin remains the village’s only green, where locals gather beside the war memorial under sugar maples.

Marietta

Marietta was the first permanent American settlement in the Northwest Territory, established in 1788 at the meeting of the Muskingum and Ohio rivers. The town is built on the grid of a frontier plan designed by Revolutionary War veterans, and it still shows. Putnam and Front Streets run parallel to the water, anchored by brick storefronts and a legacy of river commerce. Floodwalls stand between downtown and the Ohio, painted with murals that map out the town’s layered past, French missionaries, mound builders, canal traffic, oil booms.

On Putnam Street, the Lafayette Hotel faces the river and holds a rooftop cupola with views of sternwheelers that dock nearby during the Ohio River Sternwheel Festival. Across the street, the Peoples Bank Theatre shows live acts and classic films inside a restored 1919 vaudeville hall. A few blocks down, the Campus Martius Museum houses original stockade foundations from the earliest Marietta settlers. Along Front Street, Jeremiah’s Coffee House fills a former drugstore with local roasted beans, and its front windows open onto the sidewalk on quiet mornings. The river is visible at every turn, not scenic but functional, as if it still expects steamboats.

Medina

Medina’s Public Square was nearly destroyed by fire in 1870, and the result is one of Ohio’s most intact postbellum downtowns. The rebuilt district forms a near-perfect square of brick Italianate buildings surrounding a raised green. Unlike most towns of its size, Medina avoided sprawl around a bypass and kept civic life centered on South Court and Main Streets. The 1891 sandstone courthouse still marks the square’s western edge, with a working bell tower that sets the rhythm of the day.

On the southeast corner, A Cupcake a Day fills a narrow storefront with daily rotating flavors like cinnamon roll and lemon lavender. Down the block, the Medina Toy & Train Museum occupies a second-story space above a pizza shop, with operational Lionel sets and vintage games spanning a century. Castle Noel, one block south on Broadway, houses set pieces from Elf, The Grinch, and New York department store Christmas windows, all assembled in a former church. Every Saturday from May to October, the square hosts the Medina Farmers Market, where the old bandstand serves as a produce checkout and live fiddle tunes carry from one quadrant to the next.

Wooster

Wooster’s downtown was rebuilt after an 1870 fire, but its Main and Liberty Street plan has held since 1808, when the town was platted as the seat of Wayne County. The streets meet at the courthouse, a Second Empire limestone structure built in 1878. The town’s growth came not from canals or steel but from agriculture and education. The College of Wooster’s stone buildings sit just west of downtown, separated by neighborhoods of Victorian houses and alleys still paved in brick.

On East Liberty, the Blue Spruce Boutique is at 116 E Liberty and stocks Ohio-made goods beneath its original pressed tin ceiling. A block away, the Wayne County Historical Society preserves a one-room schoolhouse, a print shop, and a collection of pioneer tools in a seven-building campus off Spink Street. Spoon Market and Deli serves smoked turkey Reubens and house-baked bread inside a 19th-century grocery building with tall glass storefronts. Just south of the square, the Local Roots Market and Café sells regional produce, cheese, and meat under a worker-owned model developed by Wayne County farmers. At dusk, the courthouse clock chimes echo down Liberty, over the quiet of shops closed early and diners still full.

Tipp City

Tipp City began as Tippecanoe in 1840, a canal town built along the Miami and Erie line. Its Main Street still follows the original towpath, and many of the storefronts on East and West Main were built between 1850 and 1890. The historic district is tight, just four blocks end to end, and registered on the National Register of Historic Places. Unlike other canal towns that shifted to rail and declined, Tipp City preserved its grid, kept its storefronts filled, and expanded outward without abandoning the original core.

Coldwater Café operates inside a former bank on East Main, with its original vault repurposed as a wine cellar. Next door, Fox and Feather Trading Co. sells handmade home goods under a stamped tin ceiling. At the intersection of Main and First, the Tipp Roller Mill still stands, once a grain processor and now a seasonal concert venue. On the west end of downtown, Sam and Ethel’s Restaurant serves buttermilk pancakes and country ham from a narrow, white-painted diner that has been open since 1944. The shops close early, but the sidewalk lights stay on.

Lebanon

Lebanon’s downtown has never shifted. Broadway and Main have anchored the town since 1802, with the Golden Lamb standing on that corner longer than Ohio has been a state. The hotel’s guestbook includes Charles Dickens, Ulysses S. Grant, and 12 U.S. presidents. Broadway climbs gradually from the railroad tracks and passes under a canopy of sycamores, lined with redbrick buildings that have never been emptied or replaced. The town bypassed modern sprawl, keeping its retail and civic center where it started.

Along Main, the Village Ice Cream Parlor serves sodas in glass and fries in paper baskets inside a dining room with a pressed tin ceiling and checkerboard tile. A block west, the Lebanon Mason Monroe Railroad departs from a 19th-century depot, offering themed excursions year-round with vintage cars and costumed crews. Further down Broadway, Harmon Museum houses an art collection, Shaker textiles, and an exhibit on Ohio’s early medical history in a former post office.

Yellow Springs

Yellow Springs developed around a natural spring with a high sulfur content that once attracted health seekers by the hundreds. By the mid-1800s, it had a railroad, a resort hotel, and Antioch College, cofounded by Horace Mann, anchoring the east edge of town. The village never industrialized. Instead, it became a center for progressive politics, co-ops, and art, which shaped its single commercial artery, Xenia Avenue. The street runs straight from the railroad tracks to the Glen Helen preserve, with no franchises, no chain signage, and storefronts that change by season, not lease.

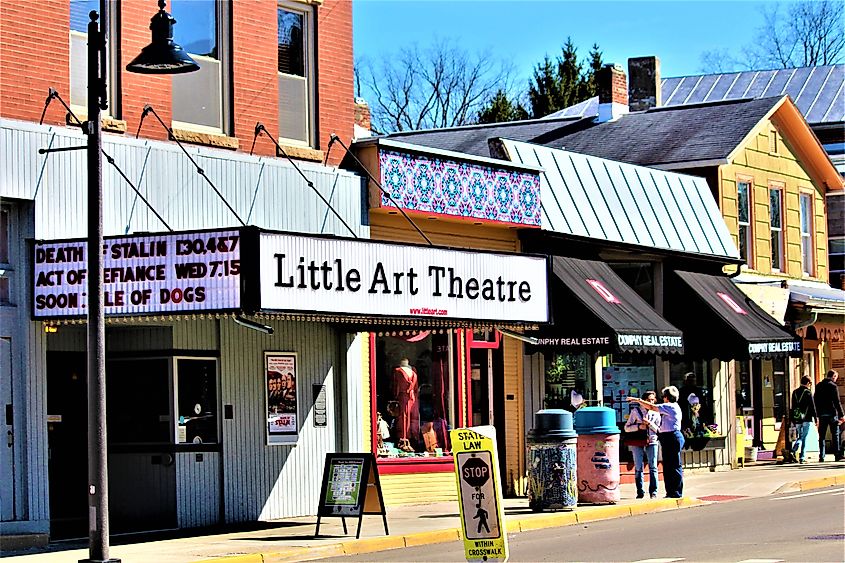

At 225 Xenia Avenue, Dino’s Coffee roasts in-house and serves espresso from a window that opens to the sidewalk. Around the corner, the Little Art Theatre shows independent and international films inside a 1929 movie house with a restored marquee. Across the street, Yellow Springs Pottery has displayed local work since 1973, managed as an artist cooperative. The trailhead to Glen Helen’s 20-mile path network sits just one block off Main, marked by the Antioch College amphitheater and the preserved stone gate. On Saturdays, Xenia Avenue closes to allow street musicians and pop-up vendors to take over the curb.

Oberlin

Oberlin was founded in 1833 as both a town and a college, designed to integrate education, abolitionism, and faith in a single grid. It became the first U.S. college to admit women and one of the first to admit Black students. The town’s main street, South Main, runs along the western edge of Tappan Square, a 13-acre commons designed by Frederick Law Olmsted’s firm. The square replaces a traditional campus and is surrounded by college buildings, storefronts, and tree-lined walks where everything, academic, commercial, and civic, intersects.

The Allen Memorial Art Museum sits just north of the square, with a collection that includes African textiles, Renaissance panels, and midcentury American prints. Lorenzo’s Pizzeria, two doors down, serves thin-crust pies and garlic knots from a street-facing kitchen that opens to the sidewalk in summer. On the south end of Main, Slow Train Café serves espresso from locally roasted beans and hosts poetry readings near the windows facing the square. The street narrows as it leaves the college and becomes residential within a few blocks.

Delaware

Delaware’s Sandusky Street has held its central role since 1808, laid out as the spine of a frontier town that once vied to become Ohio’s capital. Rutherford B. Hayes was born here, two blocks from Main, and Ohio Wesleyan University opened in 1842 with buildings that still stand behind the commercial district. The rail line cuts just west of downtown, where trains still pass at grade level. Sandusky’s storefronts remain intact, mid-19th-century brick buildings housing long-running businesses with hand-painted signs and narrow transom windows.

At 28 E Winter St., The Strand Theatre has operated continuously since 1916, screening first-run films inside a three-screen building with its original marquee and neon. Across the street, Bun’s Restaurant serves beef stroganoff, broiled walleye, and house-made pies, with booths that haven’t moved since the 1950s. On the next block, Coffeeology roasts its own beans and hangs local photography under pressed tin ceilings. Delaware’s Historical Society maintains the Nash House Museum just off Sandusky, with 19th-century furnishings and exhibits on the town’s role in the Underground Railroad. The sidewalks are wide, lined with trees, and in summer, filled with sandwich boards and café tables.

Ohio’s main streets aren’t museum pieces; they’re working ledgers of the state’s past and present. Brick blocks record canal bets, river trade, college experiments, and courthouse hours, while storefronts still sell, stage, and serve. Walk them at 5:17 p.m. and you’ll hear bell towers, horns, and vendor banter. From waterfalls to greens to towpaths, these ten corridors prove vitality is measurable in footsteps, receipts, and lights burning upstairs after dark.