Oregon Trail

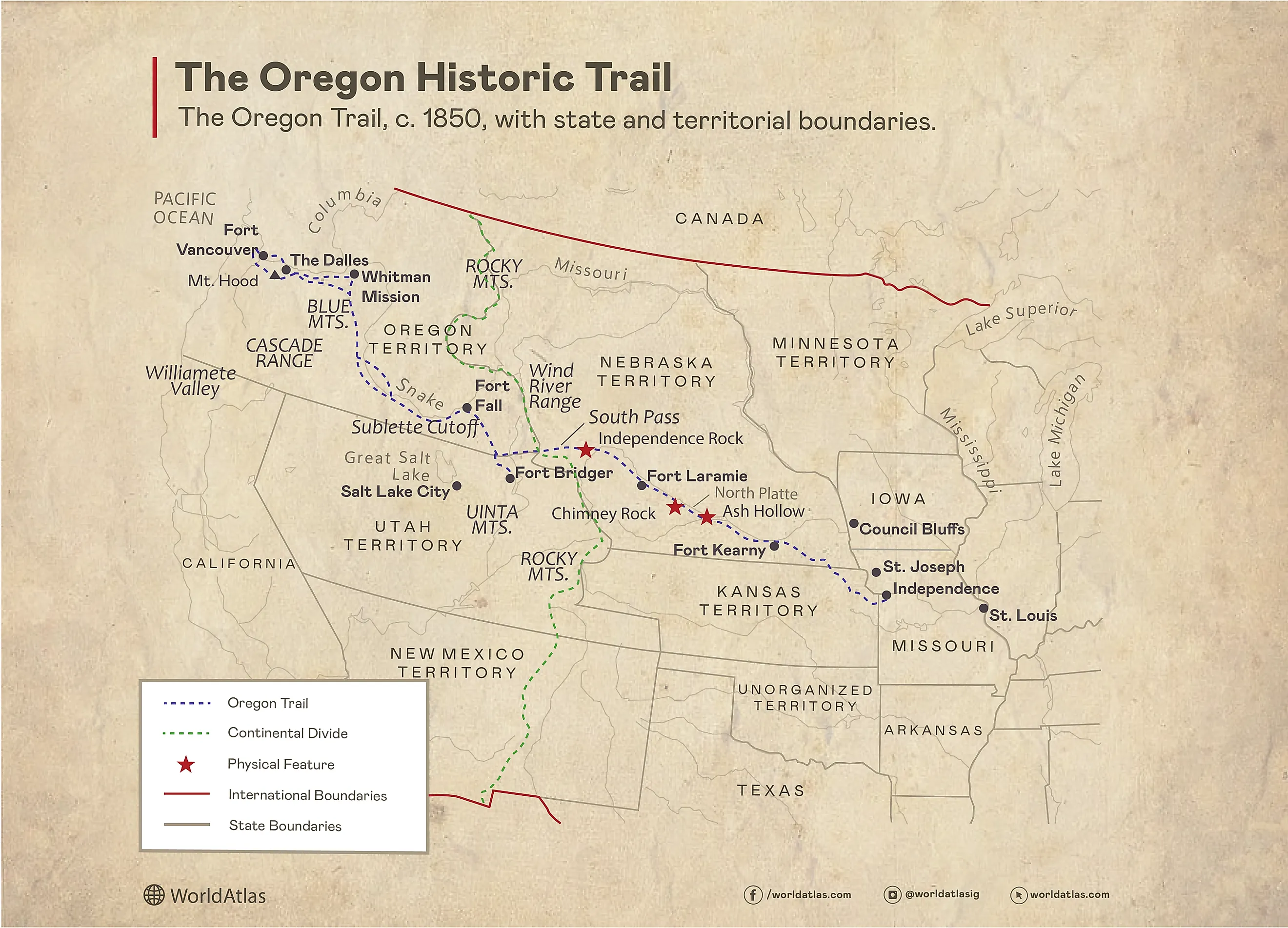

As early as 1823, explorers and fur traders were already traveling on the minor paths that would eventually connect and form the Oregon Trail. By 1834, missionaries, military, and traders were frequently using the trail for their purposes. The Native Americans had lived in the area long before all of that. But it was only in 1843, when a caravan of animal-drawn wagons left Elm Grove, Missouri, for Oregon, that the Great Emigration to the West Coast began.

The Great Emigration of 1843

If the California Gold Rush called out to the gold diggers in later years, in 1843, the farmlands of Oregon beckoned the white American farmers. Suffering from a severe depression that was affecting the Midwest, many pioneers uprooted their families to find prosperity in the West. The Oregan Trail provided the passage that emigrants used to reach the Pacific Ocean in hopes of improving their lot in life.

The Oregon Trail was a 2,000-mile pathway that began in Independence, Missouri, and ended in Oregon City, Oregon. The caravan leaving in 1843 for the West Coast was made up of 120 wagons with almost 1,000 men, women, and children and thousands of oxen and cows. This event would later become known as the Great Emigration of 1843. Some of the pioneers on this caravan were a group of Latter-Day Saints heading for Utah. The entire journey to reach Oregon took five months to complete.

Challenges Along the Trail

The emigrants crossed the Great Plains with their prairie schooners. These wagons were light and made of hardwood with an oil canvas covering. Most of them were 6 feet wide and 12 feet long and extremely uncomfortable. The pioneers loaded their food, water, and belongings on these wagons, and many preferred to walk by its side instead of sitting in it.

They followed the Platte River for over 600 miles before they reached Fort Laramie, Wyoming. Many times, the river was too swollen from the heavy rains, making it impossible to cross, especially with the wagons. If they made it to the Rocky Mountains, they had to face thunderstorms, excessive heat during the day, and bitter cold at night. There were also other dangers on the journey. Rampant diseases such as cholera, flu, and dysentery killed many emigrants. Accidental shootings, starvation, resistance from Native Americans, and drownings were also a major problem.

But if they arrived at Independence Rock in Wyoming by July 4, they knew they were halfway home. Many emigrants left their signatures on the massive granite rock, and their markings can still be seen today. It became known as the “Great Register of the Desert.”

The next big hurdle for the emigrants to overcome was the Rocky Mountains to the South Pass. Next came the steep and dangerous climb over the Blue Mountains. If they made it through that, they were almost in the clear. The final stretch of the journey was to follow the Columbia River all the way until they arrived in Oregon City.

The Legacy of the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail provided an estimated of 300,000 settlers with a way to move to the West Coast. It continued to be a workable pathway until 1888 for cattle drives. However, the railroads had already arrived and made transcontinental transportation easier for people. Before the turn of the century, the Oregon Trail had ceased to exist as the trains took over.

Today, the National Park and Service offers educational information about the Oregon Trail to the public. The Oregon National Historic Trail follows much of the same path as the original trail, and you can still see the wagon ruts on many parts of it. You can travel and view the trail either by car or even a wagon!