5 Historic Battles That Shaped Utah

People travel from all over the world to Utah because of its breathtaking scenery, which includes snow-capped mountains, expansive deserts, and towering red rocks. Beneath those picturesque vistas, however, is a far more profound tale of hardship, survival, and difficult transformations.

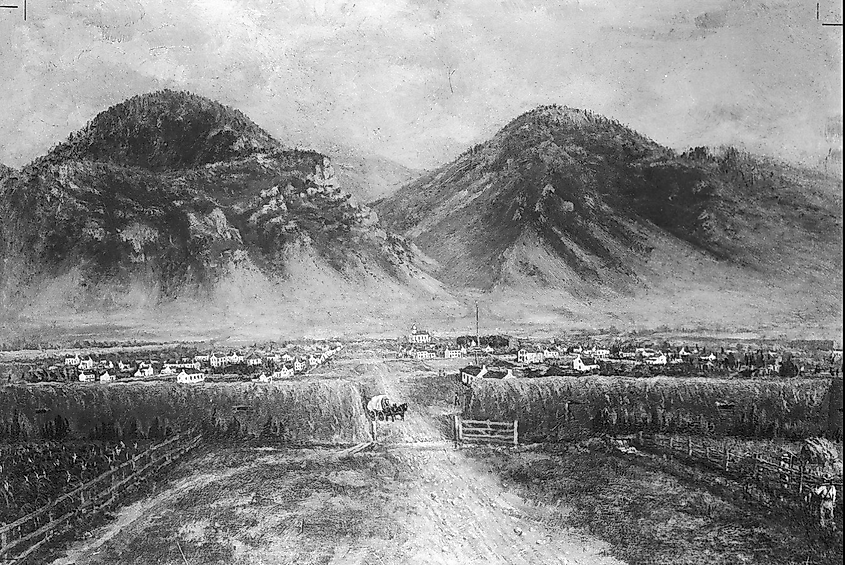

Indigenous peoples lived there for thousands of years and had a strong connection to the land long before roads sliced through it and ski resorts peppered the mountains. In the mid-1800s, Mormon settlers arrived seeking a new home and religious freedom, but as they established themselves, tensions quickly escalated. What began as competing claims over land and resources soon grew into a series of historic struggles that turned into battles that weren't just over territory, but over identity, culture, and the right to exist.

The Fort Utah Massacre (1850)

One of the major historic battles that helped shape Utah is the Fort Utah Massacre. Its history goes back to 1850, when years of tension between Mormon settlers and the Timpanogos Ute people finally boiled over. After a dispute ended with the death of a Timpanogos man, settlers, following orders from Brigham Young, attacked a Timpanogos village near what’s now Provo. For several days, Mormon militias surrounded and fought the settlement. While accounts differ, as many as 100 Native people were killed, and some were taken prisoner.

Before things turned violent, there were moments of peace. One example is Miles Goodyear, a mountain man who founded Fort Buenaventura near today’s Ogden. Married to a Ute woman, he traded fairly with local tribes and built relationships based on respect.

The Walker War (1853-1854)

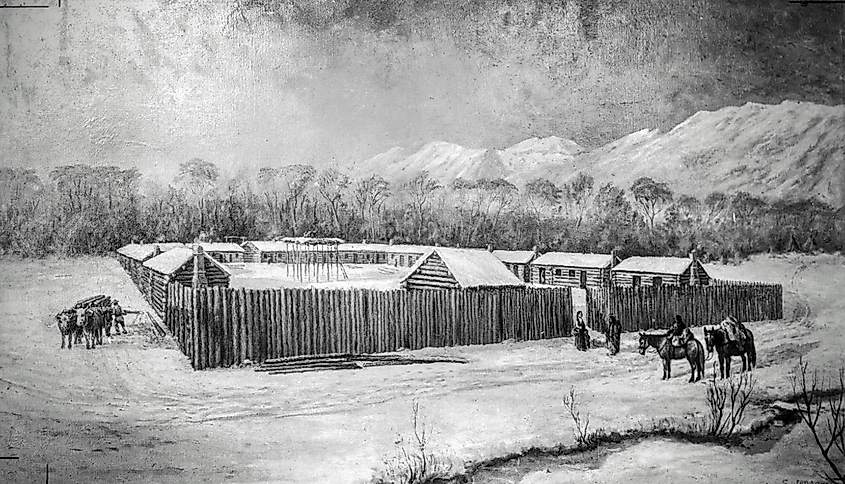

A few years after the Fort Utah Massacre took place, conflict ignited again with another historic battle. Named after Ute leader Walkara, the Walker War started in the summer of 1853. It stemmed from a deadly argument over a horse trade in Springville. The roots ran deeper, however, with broken promises, exploitative trade, and a growing settler presence that left many Utes disillusioned. The violence that followed wasn’t defined by big battles. It was a series of scattered raids, attacks on livestock, and ambushes of isolated settlements. In towns across central Utah, settlers built stockades and watchtowers, uncertain of when or where the next attack might strike.

One local story remembers Captain Stephen C. Perry of the Springville militia, who remained calm during a nighttime raid and managed to hold the line until reinforcements arrived. Though absent from most official histories, Perry’s steady leadership reportedly saved lives that night. By the summer of 1854, both sides were exhausted. Peace negotiations brought the fighting to a close.

The Fort Bridger Skirmish (1853)

Though technically outside Utah’s borders, the skirmish at Fort Bridger had major implications for the region. Fort Bridger had become a vital waypoint for travelers on the Oregon Trail, and a growing military presence there threatened Native tribes already displaced by westward expansion. In March 1853, Shoshone and Ute warriors attacked the fort in protest of settler encroachment.

The Black Hawk War (1865-1872)

Utah’s longest and most brutal conflict began in 1865 with the Black Hawk War, led by Ute war chief Antonga “Black Hawk.” After years of broken treaties, lost lands, and cultural upheaval, Black Hawk launched a series of raids across central and southern Utah. Livestock was taken, supply routes disrupted, and towns were thrown into chaos. In response, settlers, many of them ordinary farmers with little military experience, dug trenches, built forts, and formed militias, desperate to protect their homes and families.

However, it wasn’t all violence. At one point, Black Hawk reached out to Mormon leaders to seek a temporary truce. In a powerful and symbolic gesture, he asked federal Native American agent Franklin Head to cut his hair, an act in Ute tradition that showed humility and a desire for peace. Although peace didn’t come right away, the Black Hawk War gradually wound down by 1872.

The Battle of Salina Canyon (1872)

Near the end of 1872, most of Black Hawk’s resistance had crumbled. Still, violence flared in pockets, like in Salina Canyon. During this time, Mormon militia chased Ute fighters accused of livestock theft into the canyon’s narrow, rocky terrain. But instead of retreating, the Utes laid an ambush from the cliffs above. The militia, made up largely of settlers, was caught off guard by the sudden attack.

Colonel Warren S. Snow soon arrived with reinforcements and chose a different path. Instead of launching a counterattack, he turned to Chief Sanpitch, a local Ute leader known for his diplomacy. Sanpitch agreed to scout the area ahead. His efforts helped recover the bodies of two fallen soldiers without further violence.

Why These Historic Battles Still Matter

Utah’s landscapes may look peaceful today, but the past is etched into every canyon and valley. These weren’t just battles over land but struggles for identity, survival, and belonging. Indigenous people fought to protect their homes and way of life. Settlers, driven by faith and hope, worked to build new lives in unfamiliar territory. Between them were moments of conflict, but also acts of courage, compassion, and even cooperation. Remembering this history allows us to honor those who came before and gain a deeper understanding of the land and the people who shaped it.