A Love-Hate Tour Of Albania

Standing at the cusp of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas, and one of the last of the Balkan countries to open its doors to foreigners, Albania is an enigmatic, up-and-coming tourist destination — a country scattered with stoic statues, castles of the crumbling and restored sort, and fully commercialized (for better or worse) seaside cities. Shifting from the capital to the mountains to the umbrella-strewn beaches, one gets a sense of where Albania has been (i.e., the Ottoman Empire, Italian occupation, and Communist regime) and where it's going (i.e., impending over-tourism the likes of which neighboring Greece, Croatia, and Italy experience each summer).

I recently spent five weeks touring around Albania. Tirana was unusually enjoyable for a Balkan capital, Gjirokastër dazzled with its stone Old Town, and Vlorë started off strong, thanks to its waterfront promenade and sunsets plucked right out of a painting, but ultimately ended in disappointment (more on that later). Factoring in the country's shoddy bus system, some of the most psychotic drivers I've ever encountered, and a waste management culture far inferior to the European baseline, Albania left me with a mixed impression. As such, my goal is now three-fold: to talk off-the-beaten-path travellers into pulling the trigger on their trip, to convince sun-seeking vacationers to reconsider their plans, and to give an honest overview (warts and all) for all prospective visitors. Let's get into it.

Tirana (Tiranë)

Typically, capital cities (especially in Eastern Europe) are places to fly into, maybe spend a day seeing the centralized monuments, and then to promptly vacate in favor of more scenic or culturally-engaging sites. I was therefore pleasantly surprised when Tirana held my attention for an entire week. Sure, the periphery exudes that same, grey, heavily-trafficked facade that I've seen elsewhere in the East, and its interior is well-stocked with those graffitied tenements typical of post-communist cities, but Tirana also has welcoming parks, lively shopping streets, spacious public squares, and a robust coffee shop scene (not just those outdoor patios where dudes sip espressos and smoke cigarettes, but artisanal cafes in the vein of Western Europe).

I recommend booking an accommodation somewhere between Tirana Lake Park and Skanderbeg Square. This will give you a chance to immerse in Tirina's commercial and cultural core, but also retreat to a vast green space that's great for morning jogs, evening strolls, or enjoying a midday ice cream (or freshly squeezed juice) by the water.

The straight-shot distance between these anchor attractions is two walkable kilometers. En route, you'll pass the Pyramid of Tirana (an inventive vantage point), Bunk Art (a history museum installed within a subterranean, communist-era shelter), and all kinds of traditional restaurants, cocktail bars, and captivating street art overlying nearly every apartment. Then, emerging onto Skanderbeg Square (which is too large to capture in a satisfying photo), you'll be greeted by recurring Muslim prayers reverberating from the Et'hem Bey Mosque (nearly half of Albanians identify with Islam), tour groups rallying around the Opera & Ballet Theatre, and the ongoing renovations of the stately National Historical Museum (the entrance mural is still quite impressive).

Before citing some of Tirana's caveats, I'd also like to acknowledge the incredible hospitality shown by our hosts because this appeared to be universal across the country. In Tirana, as with Gjirokastër and Vlorë, (whether booked with Airbnb or Booking.com), the homeowners were friendly and exceptionally generous - regularly bringing us fresh fruits and even cooking us local dishes with no expectation of compensation (we even tried at the end and were refused). Sometimes we couldn't even come close to finishing the first bag of red grapes and plums before the next one was left at our doorstep. It was later explained to us by a local that when an Albanian welcomes you into his/her home, you become their family and their responsibility. I'm not saying for sure you'll have the same experience, but 100% consistency across three cities is a pretty solid dataset.

Caveats

Tirina gave the first taste of Albania's aggressive driving style. After vacating the airport, I was funneled into the taxi corral, which works on a set fee based on the neighborhood. My driver was an elderly man who didn't know where he was going or how to use Google Maps, and so I had to direct him (despite the language barrier or the fact that it was midnight and I'd never been to the city) all the way to my drop-off. He was heavy on the gas pedal, loose with the lanes, and when we arrived, he only took cash (and didn't have change).

Exiting Tirana was even more of a production. As of the summer of 2025, there is no central bus station - just a giant parking lot with various buses/shuttles with the name of their final destination. There's no shade, no refreshments, and no bathrooms (unless you count the wall of excrement behind the lot).

Need to get off somewhere en route? Better translate a message to your driver in advance and pay close attention to your map on your phone. Need to transfer to another bus? Good luck. My girlfriend and I got dropped off on the side of the highway en route to Vlorë and just ended up hitching a ride instead (more on this in a moment). Counting on bathroom or snack breaks? Well, you will make stops, but they will be incredibly random and done with zero communication regarding the duration. On the way to Gjirokaster, we pulled into a roadside station. Everyone used the bathroom and then rushed back to the bus (as our previous stop had been quite hurried), only to realize that our driver had disappeared. When we found him having lunch and a smoke inside the cafeteria, we realized that we had time to spare, and bought a couple of cold cokes.

Tirana also introduced us to "the Albanian stare." As I've come to understand it, because the country was closed off for so long (it opened for tourism in the 1990s, but didn't really get going until recently), residents (especially elderly ones) tend to be enthralled by foreigners. As such, you might find yourself in the scope of an unbreaking gaze with some regularity - especially if you're dressed differently or speaking a different language. It can be awkward and uncomfortable at times, but otherwise harmless. I mostly got it while jogging shirtless, but my short-haired girlfriend was hit with these staredowns more often. So just a quirky cultural thing to be aware of.

Gjirokastër (Gjirokastra)

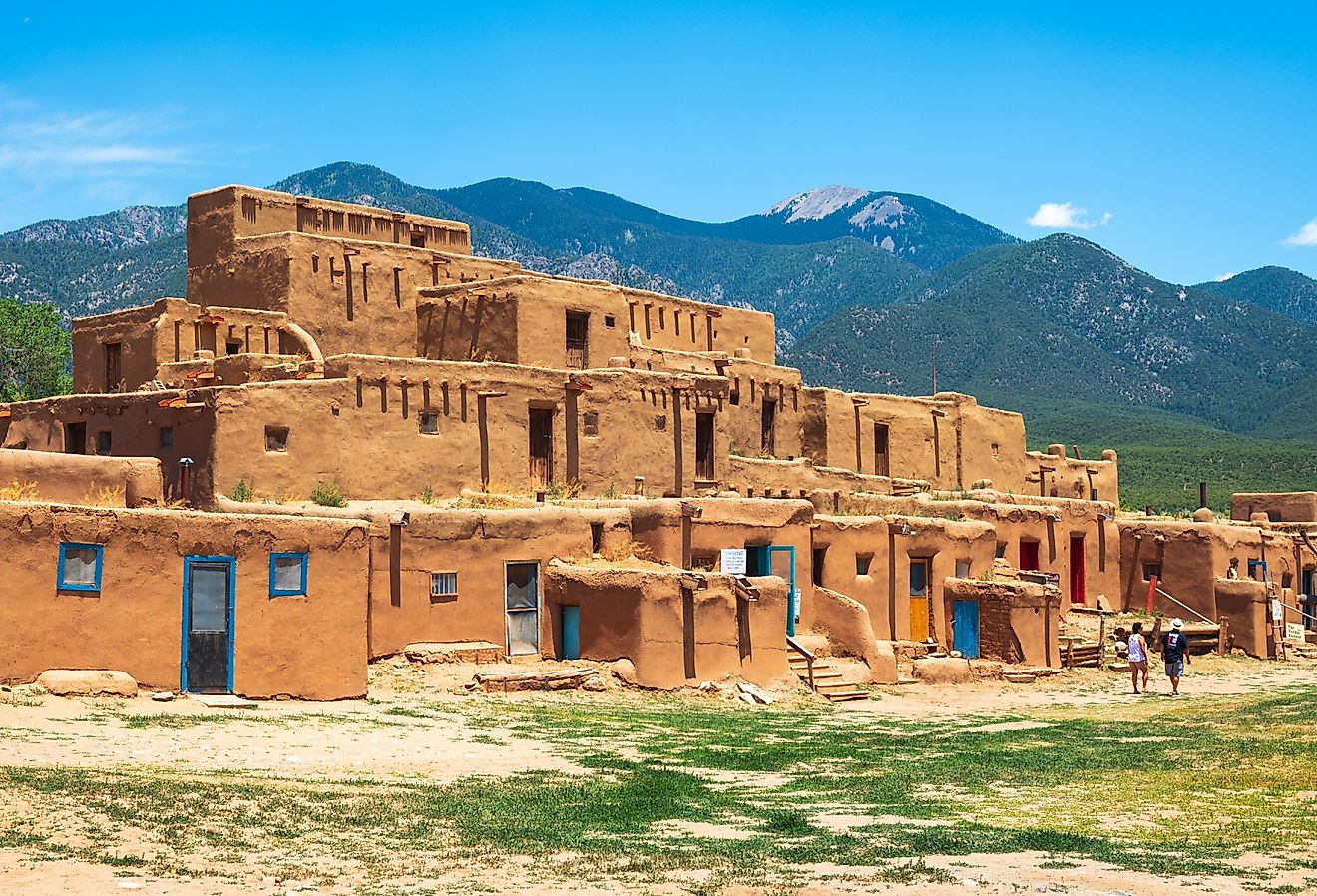

With stone structures blended high into the slopes of the Mali i Gjerë massif, Southern Albania's Gjirokastër, aka "The Stone City," has a soft, yet formidable presence. The multitude of 17th-century homes, 18th-century religious structures, and enormous hilltop fortress (which first took shape in the 12th century, was significantly expanded by famous ruler, Ali Pasha, and then used as a prison during the King Zog/Communist eras), the Historic Center/Old Town of Gjirokastra (in conjunction with its sister city, Berat) was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005. This undoubtedly boosted local tourism, though even during summer weekends, the crowds are perfectly reasonable. We never felt cramped (save for the staircase bottleneck leading up to the Gjirokastra Castle), never struggled to find a seat at a restaurant (which are plentiful and more or less ubiquitous in terms of their traditional menus and ambience), and never had to fend off fellow patrons at the little rug and souvenir shops. If anything, the moderate level of tourism added a welcome energy to the labyrinth of steep cobblestone streets.

Beyond the enshrined Old Town, peripheral Gjirokastër has plenty more up its sleeve. Its newer north side has taken on the air of a typical Balkan town. There are barber shops (got myself a sweet Albanian fade), pop-up markets, a hidden Gypsy market, unpretentious bars/cafes, and rural homes with free-roaming street dogs and cats. Venturing southward brings you higher into the yellow-grey hills, where you'll find panoramic restaurants that are well worth the trudge, scores of additional traditional homes (it's honestly like a second old town), and finally, at the end of crumbly goat trail (or rather, sheep trail), the iconic Ali Pasha Bridge - part of his groundbreaking aqueduct system.

Caveats

Gjirokastër was, by far, my favorite of the three major Albanian destinations we visited. But that doesn't mean it's without fault. Personally, I'm all about steep cobblestone streets. I like the workout, and something about it makes me feel truly transported back in time. But if you have sore joints or weak lungs, then you might have a hard time here. I know what you're thinking, but cars aren't much help. Rarely can two vehicles pass by at the same time (making for a stressful ascent/descent), and even if you're successful, the commercial core has barriers to prevent cars from entering, and its immediate periphery is a bloodbath for parking tickets.

Seasonal wildfires (i.e. April through October) is another dynamic that is out of Gjirokastër's control, but still impacts the experience. For much of our two-week stay, smoke would roll over the mountains from both the surrounding area and elsewhere in the Balkans (something I experienced before during a Fiery Vacation in Greece). Though it accented the antiquitous aesthetic, the eyes and lungs felt the strain (which didn't exactly help during those steep climbs).

I mentioned that getting to Gjirokastër on the bus was challenging. Well, getting out was a headache too. Once again, there's no bus station, just a few disparate collections of signed shuttles that congregate around the highway gas stations. If you want to go back to Tirana, or bop down to Sarandë, then you'll be fine. But getting to Vlorë (even though that's one of the country's biggest tourist destinations) was a project. We had to jump out on the side of the highway when the driver told us to (we literally had no idea where we were), walk under an underpass (no sidewalk), and then wait by some fruit stand in the hot sun for the connecting bus. We had no tickets (our driver took them) and were simply told that the next bus would come and that that driver would somehow know what the program was. While we waited, a guy lingering in front of the fruit stand tried to convince us that no bus would come and to go with him instead for 20 Euros. He claimed to be a taxi driver, but his busted, unmarked car said otherwise. Thankfully, a young Czech couple had just bought grapes as fuel for their own road trip and offered to take us for free.

Having met up with my girlfriend's parents, who drove in from Bucharest to meet us, I also got to experience driving to Gjirokastër from Vlorë (after raving about it they wanted to go to have lunch and walk around). The drivers in Albania are easily the most reckless I've ever encountered. I'm talking about quadruple passes on blind corners in the mountains, Autobahn speeds on two-lane residential roads, and lane-drifting that forces a sensible driver to always be on guard (steering onto the shoulder is a regular necessity to avoid head-on collisions). Oh, and if you come across any construction, cars will regularly cut ahead on the shoulder rather than wait in the queue (so it's up to you if you want to play by the rules).

Vlorë (Vlora)

The final stop on this three-part Albanian tour revealed its lengthy shoreline where the Adriatic Sea and Ionian Sea converge. My first impression of Vlorë was positive. Having been dropped off by the aforementioned Czech couple at a gas station outside of town, our first task was to walk much of the waterfront strip to get to our new Airbnb. Coming from the arid mountains, the sparkling sea, mixed-medium beaches, and jovial spirit of the beach town (actually, Vlorë is Albania's third largest city, but the promenade feels like a beach town) was refreshing.

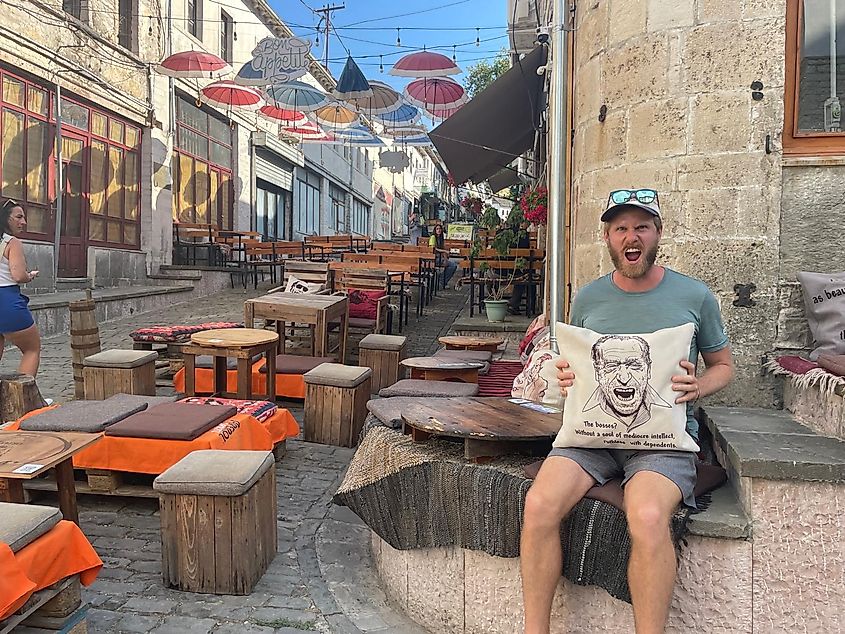

This honeymoon phase continued for another two or three days. The waterfront offered outdoor dining with some of the prettiest sunsets I've ever laid eyes on, plenty of cafes, and ice cream outlets that, frankly, became a problem (I mean this in a good way). My in-laws found a strip of beach with comfy chairs and umbrellas to rent for $10 Euros/day, and, venturing inland one day, we discovered a cute, Latin American-esque "Old Town," which, despite lacking authenticity, served as a pleasant alternative tourist magnet.

Caveats

In hindsight, a long weekend in Vlorë would have been plenty. The next ten days brought a steady decline in satisfaction. For starters, the beaches are basically giant ashtrays. Everyone in Albania smokes, and everyone tosses their butts into the sand. If you want to lay a towel out, you'll have to collect about twenty butts off the surface in order to clear a space, and then whenever you dig your toes into the sand, you will unintentionally excavate another five or so. The sea suffers in a similar way. For some reason that I cannot comprehend, people drop their plastic cups at the water's edge before going swimming, and because the water is so shallow near the shore, sunscreen run-off from thousands of vacationers amasses like an oil spill.

Shifting off the beach, the garbage problem becomes even worse. Albania uses a communal dumpster system, which means the bins are constantly overloaded. Many of the locals simply toss their trash into holes in the sidewalk, the pots of plants, or just leave it strewn about on any old stoop. Traversing the three blocks from our Airbnb to the beach, we had to pass the overwhelmed dumpsters, sidewalks full of dog poop, broken beer bottles and plastic waste, and step over a couple of those dreaded sidewalk pits. And since the beach had problems of its own, we all started to feel gross no matter where we went - including our basecamp.

I could have offered this caveat for any of the above destinations, but let's just snowball on the Vlorë rant. All three accommodations suffered from stinky drains. Something about the piping caused plumes of sewage to rise whenever the water was run. We bought candles, deodorizing spray, and dumped irresponsible amounts of cleaner down all the drains, but we were still overtaken, especially at night, by the plumes. This made us feel sick.

Feel sick turned to actual sick at the end of the first week. A combination of rotavirus, COVID, and those mysterious plagues that always seem to overtake highly commercialized beach towns rolled through our apartment. But judging by the coughs, sneezes, and vomit (which, to be fair, could have been from the rampant excessive drinking in the area), a good portion of Vlorë got hit.

One final note that can be applied to Albania in general is that you need to have cash (card is accepted at grocery stores and big tourist restaurants, but many places keep it analog). And despite the fact that the ATM prioritizes 5,000 lek bills, no one ever wants to take them. Come to think of it, any bill that was even one increment above the purchase amount tended to be a problem. A bakery in Vlorë, for instance, made delicious bread but, despite being inundated by cash-paying customers, always gave the same frowny face and head shake when confronted with anything other than exact change. One day I tried to buy a 60 lek loaf with a 200 lek bill and they literally couldn't do it. So if you have the ability to get cash out in advance of your arrival, make sure to request small denominations. Otherwise, when you make a withdrawal and get nothing but 5,000 bills, head straight to a major grocery store to break it down (even there, they still won't be happy about it).

How To Sum Albania?

After being charmed by Tirana and absolutely floored by Gjirokastër, I remarked that if Vlorë was even slightly good, then Albania would earn a spot in the upper echelon of my favorite countries. Unfortunately, Vlorë wore on me in a way I couldn't have predicted. This, in turn, caused me to revisit some of the less appealing qualities of those prior destinations (as mentioned in the caveat sections). In the end, "love-hate" is the only way I can describe this five-week-long excursion. It was exciting to see a lesser-known European country blessed with both mountains and sea, but upon crossing the border into Montenegro, I had to admit that I felt relieved. With that said, I haven't lost faith in Albania. I think with some improvements to their garbage infrastructure (and culture), enforcement of traffic laws, creation of an actual transit system, and a drop in the prevalence of public smoking, this budding Balkan destination could really turn some heads. Of course, such European-ification would inevitably lead to a higher influx of tourism, which itself would usher in new downsides. Trade-offs, my friends; travel is all about trade-offs. Perhaps in five years, Albania will find its temporary sweet spot.