The Story Of A Filipino Conservationist And The Very Rare Crocodile She Loves And Saves

Crocodiles have been feared and/or revered throughout history in many cultures around the world. Often, they have also been grossly misunderstood, associated with negative qualities, and labeled as "man-eaters." For many, the word crocodile itself is a reminder of a blood-thirsty beast hiding in the water to lunge at its unfortunate and unsuspecting prey as it enters the water, and devour it in the most ruthless manner possible. However, most fail to realize the balancing act of nature, the significance of predator-prey relations, and the crocodile's importance as a guardian of wetland ecosystems. One woman in the Philippines, Tess Gatan Balbas, however, understood the immense value of an extremely rare crocodile, the critically endangered Philippine crocodile - the world's rarest crocodilian. And she fell in love with it and decided to protect it with all her might.

The Philippine crocodile, endemic to the Philippines, has nearly vanished from the country. Tess is one of the rare few conservationists who have dedicated their lives to saving this species from extinction. Together with other team members of the Mabuwaya Foundation, Tess is fighting all odds to ensure that others too fall in love with the Philippine crocodile just like her or at least be considerate towards the creature to protect it in the wild. In 2014, she was also awarded the prestigious Whitley Award or "Green Oscars" for her commendable work in the conservation of the species. This article explores both the story of Tess and that of the fascinating crocodile she is striving to save.

World Atlas spoke to Tess to learn about the amazing work done by her and discover little known facts about the Philippine crocodile. Here is the conversation:

What ignited your passion for wildlife conservation?

Often, the seeds of passion for wildlife conservation are sown in the early years of a conservationist's life. In my case, the story is entirely different.

Born to a farmer family, I always was enjoyed living in a green environment. I could imagine myself living near a forest from an early age but was never really inclined towards wildlife conservation at that time. Later, I graduated in Forestry where I specialized in social forestry, and I was trained to be a community organizer. Even then, my focus was still very much on sustainably harvesting trees and producing timber rather than in working with wild animals.

My introduction to the world of wildlife conservation happened much later when I started working as a community organizer in a conservation and development project in one of the largest protected areas of the Philippines - the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park in Luzon. My job was to stay and work with people in remote communities, in the foothills of the mountains and at the edges of the forests. It was all a new environment for me at that time, but I just loved it!

Things were going as usual but life had other surprises in wait. In 1999, a farmer/fisherman came up to my team with an adorable looking baby animal, a little crocodile that to our extreme amazement turned out to be the world's rarest crocodile species - the Philippine crocodile or Crocodylus mindorensis.

The discovery created a great deal of excitement at that time as it was thought that the critically endangered Philippine crocodile was extinct in Luzon, our country's biggest and most populous island. Only small populations of the species were known to survive in the southern Philippines.

Soon, the baby crocodile became the apple of our eyes. We treasured it more than anything else. From time to time, I was tasked to feed it. And it is during this time that I developed a close association with the Philippine crocodile. I learned how special and rare it was and was shocked to know how it was nearly extinct. That sowed the seeds of passion and compassion for the species in my heart.

However, the NGO where I worked during the rediscovery of the species stopped operating in the region in 2001. At that time, there was no one left to continue the work for the Philippine crocodile conservation. However, luck struck both the crocodile and me when an NGO called the Mabuwaya Foundation was founded in 2003 as a joint venture by a group of enthusiastic Dutch Scientists and Filipino conservationists. It aimed to continue the vital research and conservation work urgently needed to protect the species in the wild.

Mabuwaya is a very special word. In fact, it is a contraction of two words: Mabuhay meaning "Long live" and Buwaya meaning "Crocodile" So.. "Long live the Crocodile!"

The Mabuwaya team, which was initially mostly focused on research, was soon looking for a community organizer, as research itself was not going to save this species from extinction. I was excited to receive the offer for the position but at the same time, was hesitant at first. I was aware that a massive challenge and great responsibility was associated with the job. Convincing people to fall in love with crocodiles? Was it possible? However, I did accept the challenge and today, continue to thoroughly enjoy my work with our remarkable and devoted team.

So, when did you formally start working on the conservation of the Philippine crocodile? Tell us about the initial days.

My formal entry as a Philippine crocodile conservationist began in 2004 when I started working full time as a community organizer for the Mabuwaya Foundation. My task was to convince the local communities and politicians that saving the Philippine crocodile was necessary and that their wetland habitats must be kept intact and not indiscriminately converted to rice-fields.

Getting people to see a crocodile with compassion was quite a tough job in the beginning, especially when these predators already had a very tarnished image in the Philippines. They were viewed as being greedy animals with a lust for killing humans. There is also a culture of comparing corrupt politicians with crocodiles in the country.

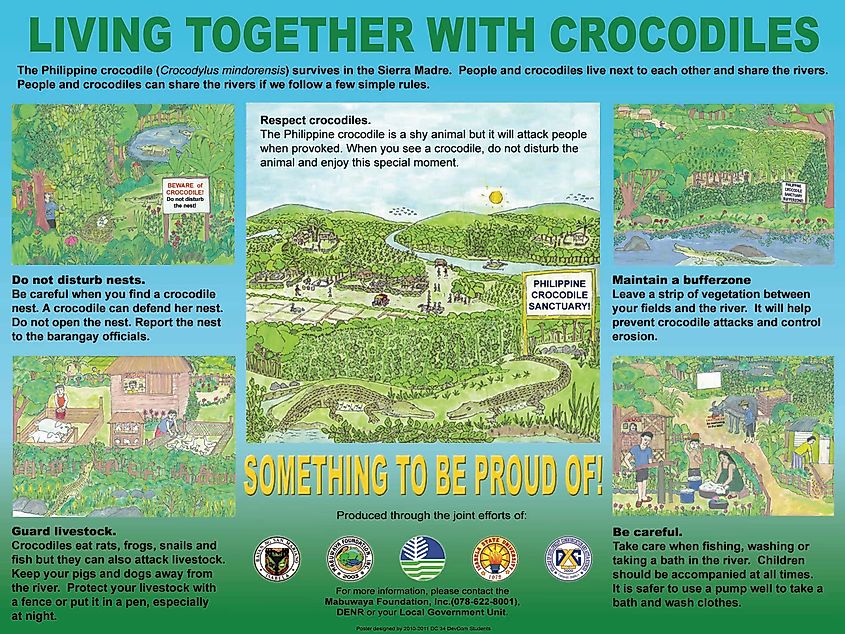

Given this reputation of crocodiles, we had to think of innovative ways and experiment a lot to convince the people to conserve the Philippine crocodile. We used the community-based conservation strategy as a tool for doing so.

Please brief us on the work done by you and your team today in conserving the species.

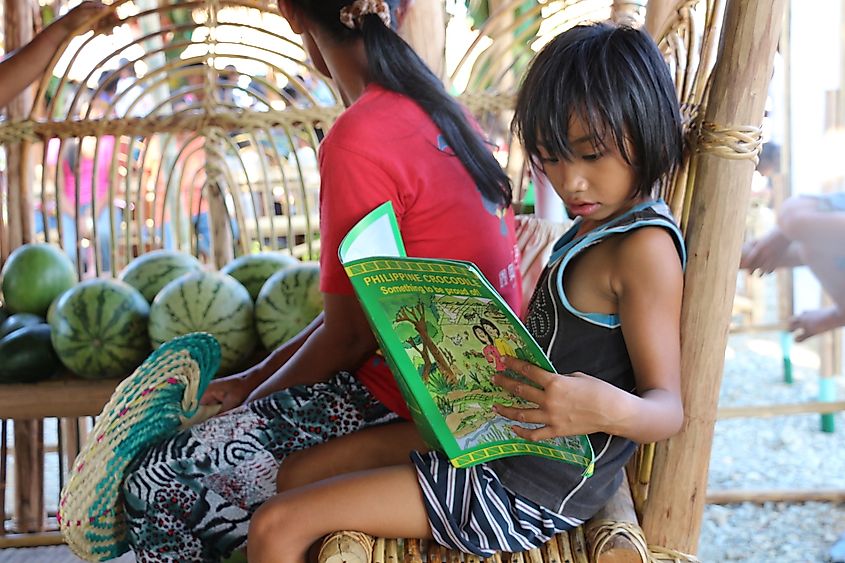

Today, our work has expanded a lot but the approach remains the same. We work closely with local governments and communities. We conduct intensive communication campaigns at all levels in society. It is very important to tap the young minds to think about wildlife conservation. Hence, we also host numerous awareness programs involving school children like lectures, puppet shows, etc.

We produce storybooks and invite school children to come with us on field excursions to see the wild crocodiles. We also celebrate festivals dedicated to the Philippine crocodile and distribute posters and calendars promoting the conservation of the species to homes near prime crocodile habitats.

We train communities in environmental stewardship and land use planning. We also assist local communities to shift to more sustainable land use such as agroforestry instead of monoculture agriculture.

What is the current conservation status of the species in the Philippines and how has it changed over the decades?

There was a time when the Philippine crocodile used to be widespread in the country. Spanish explorers reported crocodiles from all major river systems, but these could be either Saltwater crocodiles or Philippine crocodiles, as both species occur in the Philippines. Philippine crocodile specimens were collected in the 19th and early 20th century from upland river systems of most larger islands of the Philippines except Palawan. The species was described from a specimen collected on Mindoro Island, hence the scientific name “Crocodylus mindorensis.”

Unfortunately, however, unregulated hunting for its skin and wetland conversion led to its extinction on all islands except Mindanao and Luzon. Even on these islands, it survives in only a few remote localities, including Isabela Province on Luzon where I work. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species categorizes the Philippine Crocodile as critically endangered with less than 150 mature individuals in the wild. It is considered to be the rarest and most threatened crocodilian species as well as one of the rarest animals in the World.

What are some of the fascinating facts about the Philippine crocodile?

I always joke during community presentations that the Philippine crocodile is truly a Filipina like me because it is small, shy, and beautiful and does not attack unless provoked.

These animals grow to a maximum of 3 meters and do not eat people!

They live in upstream rivers and creeks and also spend a lot of time on land. One of our radio-tagged crocodiles even spent a whole week in the forest away from water. We thought it had died, but when we found it, it was fully alive! That was fascinating!

In one of the areas where we work, crocodiles use caves as shelter.

Another notable fact is their ability to make both hole nests and mound nests. Hole nests are dug in the ground and covered with soil and vegetation while mound nests are large heaps of vegetation. We think they use these two different nesting methods to increase nesting success and avoid predation. In a study we conducted in 2008, all mound nests were infested by exotic killer ants who kill crocodile hatchlings, while hole nests did not have ants. But if there are no ants, the mound nests seem to be more successful in terms of egg hatching rates.

Their diets are also quite interesting. In a recent study of the Philippine crocodile diet, we found that snails are an important prey item for both small and larger crocodiles, including the introduced Golden Apple Snail which is a pest in rice fields. We are now using that information in our communication campaigns to show farmers that crocodiles are useful animals in controlling rice pests such as introduced rats and snails.

What are the major threats facing the Philippine crocodile?

There are many threats to the species.

Habitat loss is still a major threat to Philippine crocodiles. Marshes and ponds are converted into rice fields.

Small creeks are dammed to impound water for irrigation, and larger rivers for hydropower production, impacting water flows.

Illegal fishing methods such as the use of electricity and dynamite depletes prey species for crocodiles and also pose direct threats to crocodiles themselves.

Although killing crocodiles is now illegal under Philippine law, it still happens from time to time.

What are the major challenges to its conservation?

Compared to other charismatic endemic species such as the Philippine Eagle and Philippine Cockatoo, crocodiles are seen as monstrous creatures capable of inflicting harm on animals. What people fail to realize is that the Philippine crocodile is a relatively small and shy animal that will not attack people unless provoked. If it eats livestock, it is only because the natural prey species are no longer around or not available in sufficient numbers.

So, the major challenge is changing perceptions of the masses. I need to be convincing enough to delete the negative image of the crocodile from the minds of the people, an image that has been integrated since childhood and over generations. Once that change has been triggered, the rest is easy. When the masses take pride in their indigenous animals, they make all efforts to protect them.

Law enforcement is another massive challenge. No one has ever been convicted for killing a crocodile as authorities would always reason: let’s pity them because they are poor farmers. Politicians often ask us: for whom do you care more, the people or the crocodiles? For us, it is obvious that we are concerned with the wellbeing of both the crocodile and the people, as wetland conservation also benefits local communities. Most, however, are not aware of the same or are not ready to listen.

Sometimes the negative reactions by some people do discourage me to continue with my work. But the next day, I am up and working again because I know what I am doing is so necessary. I continue to see hope and believe the species can be saved and with it, entire ecosystems as well.

Funding sustainability or a reliable source of funding is another major need. Most of our loyal donors are zoos that have Philippine crocodiles. With the COVID 19 outbreak, their donations to our conservation work are already being affected.

What actions are being taken in the country to protect the species?

Our Foundation, the Mabuwaya Foundation works with local communities to conserve and protect the Philippine crocodile in its natural habitat. We have helped communities set up 8 crocodile sanctuaries and 13 fish sanctuaries. Together with the Local Government Unit of San Mariano, we trained local sanctuary guards to enforce environmental laws and the sanctuary ordinances. The sanctuary guards also count the crocodiles every quarter. Many people say there is less erosion and cleaner water and more fish as a result of the sanctuaries. Many also enjoy the sight of wild crocodiles and are not afraid of them anymore.

The Philippine Government protects the Philippine crocodile and other threatened species through the Republic Act 9147 (Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act of 2001). The Wildlife Act prohibits the collecting, wounding, and killing of all wildlife species including the Philippine crocodile. In southern Philippines, another NGO is also working to protect the remaining crocodiles of Mindanao.

What are some of the major achievements of the conservation work done by you and your team members?

The Philippine crocodile was already considered extremely rare, and extinct on Luzon Island, in the early 1980’s when the first national survey was conducted. After the surprising rediscovery of the species in Isabela Province, we immediately started working for the conservation of this species in 1999 with less than 20 individuals in the wild in 3 distinct areas in the municipality of San Mariano. With our intensive communication campaigns and by assisting communities to protect their wetlands, the Philippine crocodile population in San Mariano slowly started increasing. We now have almost a hundred Philippine crocodiles in the wild in five areas. The killing of crocodiles has nearly stopped. The local government even declared the Philippine crocodile their flagship species, a brave step indeed as crocodiles here are associated with corrupt politicians!

What are your future goals regarding the conservation of the Philippine crocodile?

Our goal in the foundation is to continue working with communities for the protection and conservation of the Philippine crocodile so we can delist it from its current status. We would also like to ensure that communities and indigenous people benefit from protecting this species and its wetland habitat through earnings from eco-tourism, practicing green livelihoods such as agroforestry in crocodile sanctuary buffer-zones, enjoying higher fish catch, and cleaner and abundant water for daily use and irrigation.

What would be your message to the world about why it is important to save the species?

The Philippine crocodile, just like other threatened species, urgently need much greater attention for its successful conservation. These reptiles are still at the brink. It would be such a pity if these remarkable animals vanish from our planet and remain confined to the pages of a book or in photographs.

The Philippine crocodile poses a challenge to the entire world. If it can be saved, it will prove that nothing is impossible. With our will and determination we can undo our past wrongdoings, fight climate change, and save any other species that is threatened with extinction.

I am confident that everyone would soon realize the significance and magnificence of the Philippine crocodile. Once the masses are aware and take an active role in its conservation, the Philippine crocodile would survive and thrive and serve as a symbol of a bright future for our coming generations.