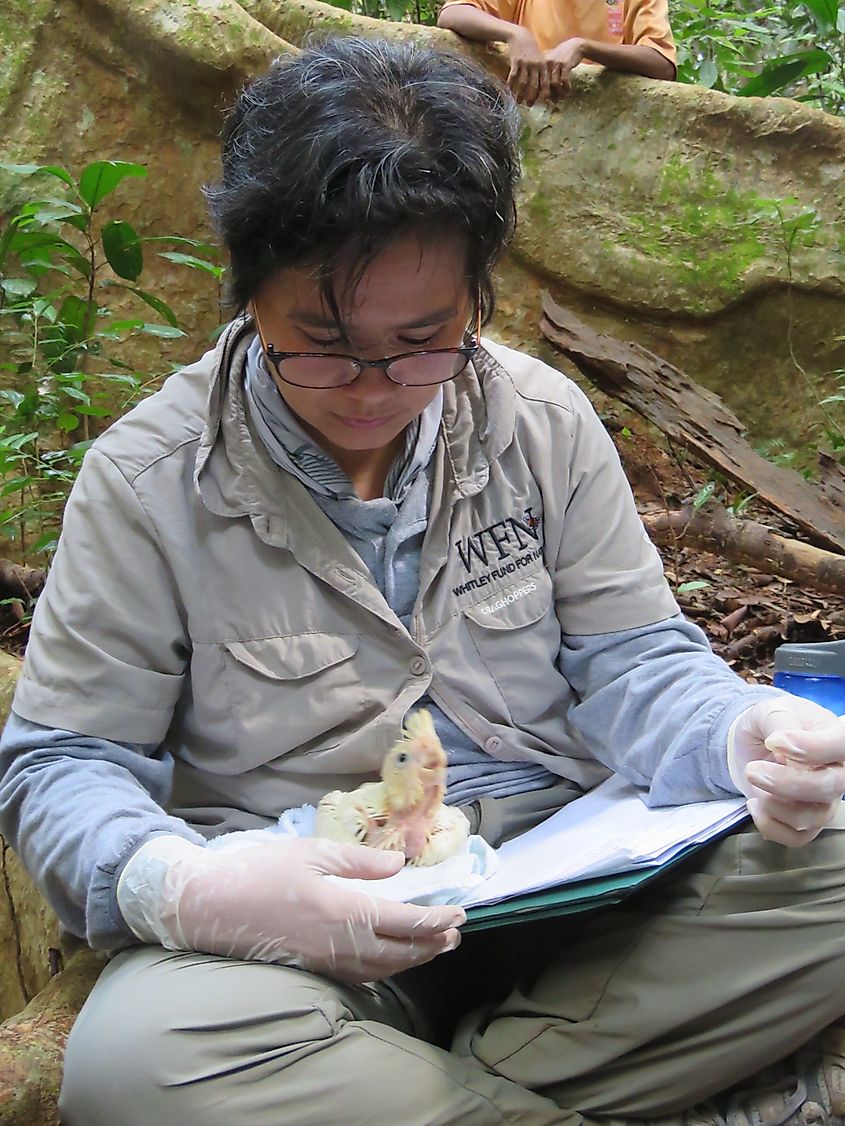

Meet The Filipino Wildlife Conservationist Who Is Saving A Fast Vanishing Cockatoo

In the remote picturesque islands of the Philippines, a very rare bird, the Philippine Cockatoo, is struggling to survive. For decades, people's desire to keep this gorgeous bird encaged in their homes has led to its rapid removal from the wilds. Today, the lowland forests in the Philippines that serve as home to these birds are also fast disappearing. Given the humongous threats looming over the species, and their critically endangered status, most would have given up hope of ever saving the bird. However, a determined wildlife conservationist Indira Dayang Lacerna-Widmann and her colleagues from the Katala Foundation (Katala is the local name for the bird) were ready to face all hurdles to keep the bird alive. Not only did they manage to give the Philippine Cockatoo a new lease of life but they also brought positive changes in the lives of prisoners and ex-poachers by giving them a chance to participate in their conservation activities. Indira's commendable work was also recognized by the Whitley Fund for Nature in 2017 when she was selected as one of the winners for the prestigious 'Green Oscars' award.

World Atlas had the opportunity of speaking to Indira and learn about her life, work, team members, and of course, the bird that she is so in love with! Read her story below:

How did you develop your passion for wildlife conservation? What/who inspired you?

I was close to nature since childhood. It was my father who introduced me to outdoor adventures. He always encouraged me to explore the world outside my home and taught me skills that I find extremely useful today. Since my early years, I would swim around in local ponds, the wharf, and against raging river currents. I would enjoy farm life, plant trees, interact with animals, play outdoor games, and even get hurt while playing. My Papa always encouraged me in my exploits. He also taught me how to interact with a variety of people. Little did I know then that the people management skills taught by him would come in extremely handy in the future. My mother too played an immense role in shaping my future. She always wanted the best for me and my three brothers and an elder sister. She coached me for literary contests during my school days. She was a determined woman and an achiever. Hence, we were all taught to aim for the highest and take interest in our studies. The values instilled by my parents during my childhood continue to aid me in my conservation work today.

Another person who had immense influence in my life and continues to inspire me to this day is my life partner, Peter, a hard-core field wildlife biologist. I met him while working on a Philippines-Germany bilateral program on Applied Tropical Ecology. He had great faith in my abilities and encouraged me to aim for higher goals. In fact, it was he who introduced me to the enchanting wild world of the Philippine cockatoos.

How did you direct your education to allow you to pursue your passion?

I completed a Mass Communication course in college, participated in the Applied Tropical Ecology Program in Leyte, and pursued a Master of Science in Environmental Studies at the University of the Philippines Los Banos. A turning point in my life was the opportunity to attend a diploma Course on Conservation Education at the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK. For this course, I was awarded a scholarship by the Critical Ecosystems Partnership Fund (CEPF) to the Rare. This NGO selected me as one of the nine people across the world and the first one in the Philippines to implement the Pride Campaign to save a species. In my case, it was the Philippine Cockatoo.

When did you start working for the conservation of the Philippine Cockatoo?

I started working on the conservation of the species with Peter in 1998 on the Rasa Island in Narra, south of the provincial capital of Palawan. His initial investigations revealed that around 23 to 25 Philippine cockatoos inhabited the small coral island. With the belief that the population could be enhanced, we started working with the community on the island to protect the birds.

What are some of the fascinating facts about the Philippine Cockatoo

When I came to work for the Philippine Cockatoo – the first sight of the bird alone left a deep imprint on my mind. Here are some of the features of this bird that I find extremely captivating:

- The beauty of the bird. The red-orange plumage on the vent lends a splash of colors to its overall fluffy white plumage and white crest. Its white plumage is extremely conspicuous in flight and the foliage cover of its habitat.

- The high level of intelligence exhibited by these cockatoos is also to be noted. It has been compared to that of primates. Possibly, these birds are more intelligent than dolphins and elephants. Very often they outsmart our field teams when we are working with them in the wild by showing up in unexpected places or exhibiting new and unusual behavior. Research on a very closely related species has shown that cockatoos are not only adept at using tools but can also produce tools, as well as solve complex problems.

- There is also some indication that these birds self-medicate and that they travel quite far to visit particular plant species with specific active components.

- Its gregarious and adaptable nature. The Philippine Cockatoo is a very social species that fly in noisy groups and forages on a variety of plant matter including crops.

- The Philippine Cockatoo breeds only once a year. They produce a clutch of 2-3 offsprings (average 1-2).

- Its popularity. The bird is called by many local names in different parts of the Philippines where a few decades ago they occurred in large numbers. It is called Katala and Kalabukay in certain parts of Palawan. It is also named Agay, Kalangay, or Abukay by the Visayans.

What is the current conservation status of the Philippine Cockatoo?

The Philippine Cockatoo is listed as 'Critically Endangered' by the IUCN and the Philippine Red-List. Our recent estimate of the global population of this bird is 830-1230 individuals. About 70-90% of this population is found in the archipelagic province of Palawan, the westernmost archipelago of the Philippines. Within this archipelago, the majority of the birds inhabit the four project sites where we work. There are remnant populations on the islands of Bohol, Samar, and Polillo. After Palawan, the second-biggest population of this species can be found in the Sulu Archipelago. Outside Palawan, the populations of the Philippine Cockatoo are very small. Also, except for Palawan and Sulu, most other regions hosting the Philippine Cockatoo do not have reproducing populations of the bird. Hence, we are concentrating our work in the Palawan province where there is still hope.

What are the major threats to the survival of the Philippine Cockatoo?

Habitat loss is currently the biggest threat to this beautiful bird. Its lowland forest habitat is subjected to several scourges including illegal tree cutting, the encroachment of human settlements, conversion to agricultural lands, road construction, and slash and burn farming practices, among others. The birds are also illegally captured for the pet trade. Many birds get killed in the process. Although the inclusion of the species in the CITES Appendix I has significantly reduced international trade in the species, local exploitation of the bird continues to this day. The ability of this intelligent bird to mimic human voices makes it an attractive pet in local households. Another cause of concern is a viral disease called the Psittacine Beak and Feather Disease (PBFD) which is affecting the pet parrot population in a big way. It also renders the wild cockatoos susceptible to the disease if they come in contact with the captive parrots. Hence, we conduct thorough checks on all our Katala hatchlings every year to ensure they are in good health. The Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and the University of the Philippines aid us in this activity.

Please brief us on the founding of the Katala Foundation.

When we started working in 1998, we had very little funding but the hard work put in by our local colleagues and community members kept us going. Just a year later, we celebrated the birth of cockatoo fledglings. In 2000, we had our big break when our work was featured on the national television in an environmental show hosted by Juan Miguel Zubiri. Later, Miguel played a prominent role in helping us to establish the Katala Foundation. In 2002, the organization was formally registered. Since then, there has been no looking back. Today, we work for the conservation of not just the Philippine Cockatoo but a host of other threatened and endemic fauna including the Palawan Hornbill, Palawan Forest Turtle, Palawan Pangolin, Calamian Deer, Balabac Mousedeer and others.

How is the Katala Foundation working to protect the Philippine Cockatoo?

We believe in adopting an ecosystemic and participatory approach to conserve a species. We conduct scientific research on the ecology and biology of the Philippine cockatoos. We involve the local communities in our fieldwork. We also strive to restore, protect, and manage the existing habitat of the bird, its nesting sites, and expand its presence to newer areas. Conservation education is also our top priority. We wish to bring behavior change among the local populace so that they start taking pride in the Philippine Cockatoo and other wildlife surrounding them.

The Katala Foundation has involved ex-poachers/illegal traffickers as wildlife wardens. How has that helped in the conservation of the birds?

As mentioned before, we believe in a participatory approach towards conservation. Hence, we have appointed ex-poachers/illegal traffickers who are all members of the local communities, as wildlife wardens in our projects. In exchange for a small but stable income, these people have stopped their illegal activities, thus eliminating a major threat to the Philippine cockatoos to a great extent. The indigenous knowledge and skills of these ex-poachers have also been useful in the implementation of our conservation activities in situ. It is also heartening to see how these people now take pride in their work as protectors of wildlife rather than destroyers. Their work has been featured in international documentaries and media channels like BBC and National Geographic motivating them further. For all this, we would like to thank the supporters of our wildlife warden scheme including the local governments, Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, private landowners, and volunteers.

Prisoners and ex-convicts also participate in saving the bird through your conservation projects. How did that become possible?

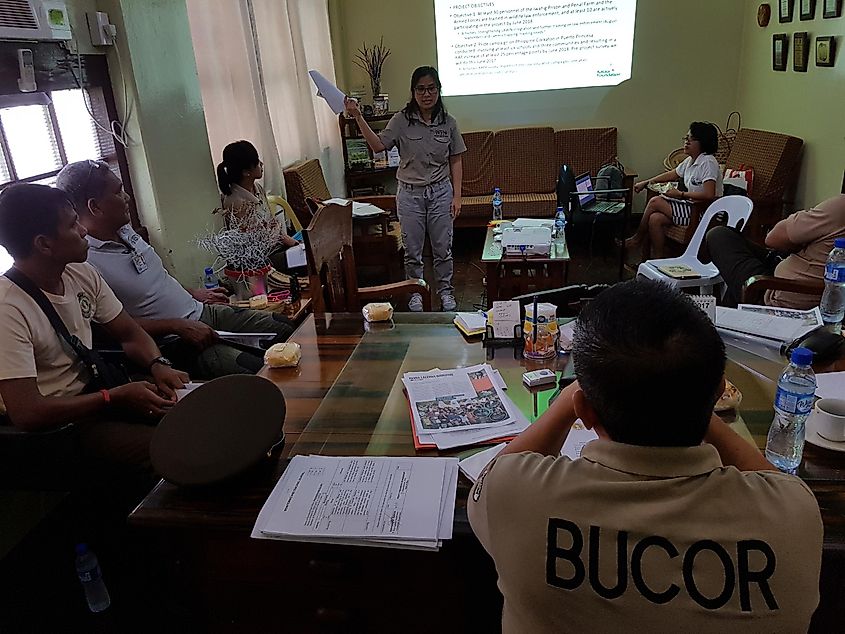

In the early years in the Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm (IPPF), persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) were allowed to roam in the lowland forests surrounding the penal colony. Many of them came to learn about the birds and their nesting sites during this time. Some also resorted to the illegal trafficking of these birds. But we saw potential in them to steer them towards positive work. With the permission of the management of the IPPF, we engaged some of the PDLs and ex-convicts in our conservation program. They were tasked with monitoring the Philippine Cockatoo populations and add their observations to our database. We also have a nursery nurturing native plants for our habitat restoration programs. The plants at this nursery are solely taken care of by the PDLs assigned by the IPPF management. We are glad that the Bureau of Corrections personnel at the IPPF are active partners of our patrol, nest checking, and habitat monitoring activities.

What are the major challenges faced by you and your colleagues in protecting the Philippine Cockatoo?

We often have to work in remote project sites where law and order situations are usually volatile. In some places, working without the aid of police or military escorts is not possible. The logistical challenges thus incurred also increase our operational costs. Another big hurdle is the fact that biodiversity conservation is not always the top priority of the region. Although local governments constantly support us in our activities, individual local officials can impede our conservation pursuits when their personal agendas clash with their public obligations. Currently, funding is also a big issue for us. The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak has created a paucity of funds as many of our donors, especially our zoo partners, have incurred significant losses themselves.

Despite the challenges, what keeps you motivated?

The look in the eyes of the rescued cockatoos gives me hope. Also, the very thought of protecting a species that numbers less than a thousand instills a sense of great responsibility in me. Even after 20 years, I feel the same excitement I felt initially when I put leg bands on the new batch of hatchlings every year! The simplicity, genuine display of gratitude, extreme honesty, and diligent work attitude of the local people including the ex-poachers and the PDLs also serve to inspire me a lot. Their trust in us makes us feel more resolved to carry on with the fight against all odds.

What are your future goals regarding the conservation of the Philippine Cockatoo?

A lot is left to be done. Recovering Philippine Cockatoo populations at all our actively managed project sites gives us hope. Now, more than ever, concerted efforts from conservationists and all stakeholders are needed. We must remember that all the existing sites of residence of the Philippine cockatoos except for two are not formally protected. Also, layers of protection need to be added to all the sites to secure them for the future survival of these birds. The biggest concern is that given the current development spree in the Philippines, the available habitat for the species is actually decreasing and not the other way round. The introduction of the species to other parts of its formal range is also one of our future goals. And to top it all, a measurable goal would be the stepwise down-listing of the species on the IUCN Red List, where it currently occupies the highest threatened category.

What is your message to the world about why it is important to save the species?

Like every other species, the Philippine Cockatoo is unique and very special. It is the pride of the Philippines, a symbol of our rich natural heritage. It also occupies a special place in the hearts of the people of the local communities that have lived with these birds for centuries. The ancestors of the Philippine Cockatoo trace their origin to Australia from where they came to the Philippines by an incredible feat of island-hopping which lasted over several millennia. Today, it serves as a flagship species whose conservation leads to the protection of many other rare and endangered flora and fauna of the country that shares its habitat. So, I would request the world to fall in love with this bird and ensure its brighter future.