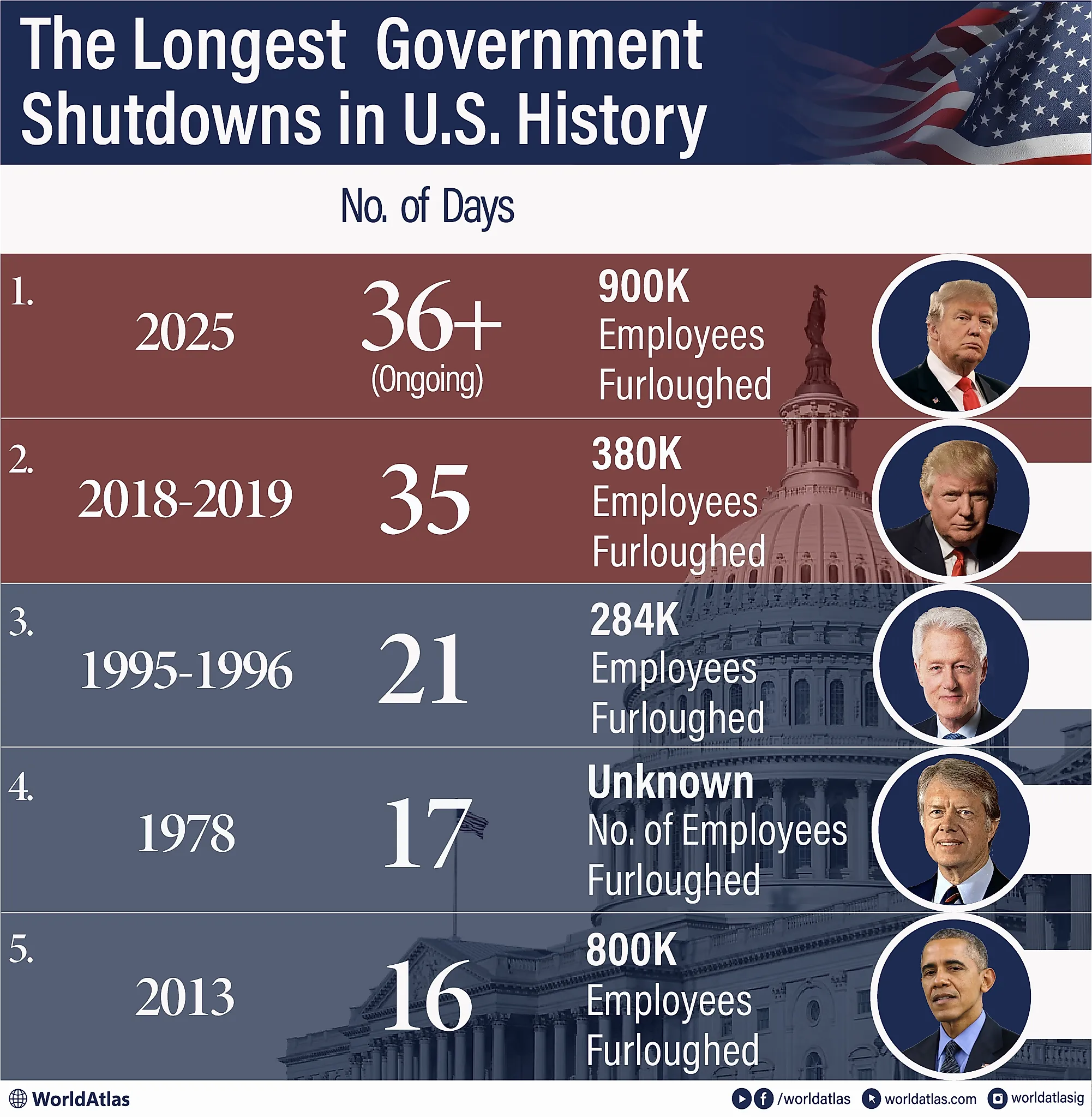

The Longest Government Shutdowns In US History

What happens when the world’s largest government hits the pause button? Paychecks stop or arrive late. Court dockets stall. National parks lock their gates. Airports snarl. Families ask how to buy groceries if SNAP benefits lapse. And all of it turns on a handful of votes and a signature. Why do shutdowns recur in the U.S.? Do they save money, or waste it? Since a 1980 Justice Department interpretation of the Antideficiency Act made funding lapses bite, shutdowns have become a recurring stress test of America’s separation of powers. Below are the five longest, what sparked them, and what they cost.

Long-Story Short

An American government shutdown happens when the federal government’s funding doesn’t become law by the deadline. The House and Senate must pass the same budget (or temporary fix), and the President must sign it. If either chamber can’t agree or the President vetoes the bill, agencies lose authority to obligate or spend money. Under the Antideficiency Act that came into effect in 1980, most operations must pause, except those protecting life or property, until new funding is enacted. In short, any one of the three, the House, the Senate, or the President, can block funding and trigger a shutdown. Read more about the current shutdown here.

A shutdown ends when Congress passes and the President signs full-year appropriations or a temporary continuing resolution. Alternatively, Congress overrides a veto with a two-thirds majority. Agencies then restart operations, pay back wages, and resume obligations under restored legal spending authority.

Do shutdowns save money? No. They typically cost more: back pay, lost fees and tax compliance, contractor premiums, economic drag, and lost productivity, while rarely resolving the disputes that created them.

The 5 Longest Government Shutdowns in US History

| Rank | Year | No. of Days | President |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2025 | 37 (ongoing) | Donald Trump |

| 2 | 2018-2019 | 35 | Donald Trump |

| 3 | 1995-1996 | 21 | Bill Clinton |

| 4 | 1978 | 17 | Jimmy Carter |

| 5 | 2013 | 16 | Barrack Obama |

1. 2025, 37 days (ongoing)

- President Donald Trump

- Senate/House: Republican.

The fiscal-year 2026 funding lapse began on October 1 after Congress failed to pass a bill both parties would accept. At the core is whether to extend enhanced Affordable Care Act subsidies; Democrats insist on including them, while Republicans and the White House push a "clean" stopgap first. On November 5, it became the longest shutdown in U.S. history. Aviation authorities ordered flight reductions as unpaid controllers and TSA agents strained operations, and courts prompted partial, delayed SNAP payouts during the lapse. Republicans control both chambers but lack 60 Senate votes to beat a filibuster, so House-passed measures have stalled. Talks continue, with GOP leaders rejecting calls to scrap the filibuster.

2. 2018-2019, 35 days

- President Donald Trump

- Senate/House: Republican.

This partial shutdown began on December 22, 2018, when the president demanded $5.7 billion for new barriers on the U.S.-Mexico border, and Democrats refused. About 380,000 federal employees were furloughed, and 420,000 worked without pay across unfunded agencies. Nine executive departments were affected, closing parks, delaying immigration hearings, and slowing approvals. The CBO estimated an $11 billion economic hit, including $3 billion permanently lost. After weeks of stalemate, widespread air-traffic controller absences triggered major delays, and leaders agreed to a three-week reopening on January 25, 2019, to negotiate without wall funding. Congress later provided limited fencing funds; broader demands shifted to other legal channels. Many contractors never received back pay nationwide either.

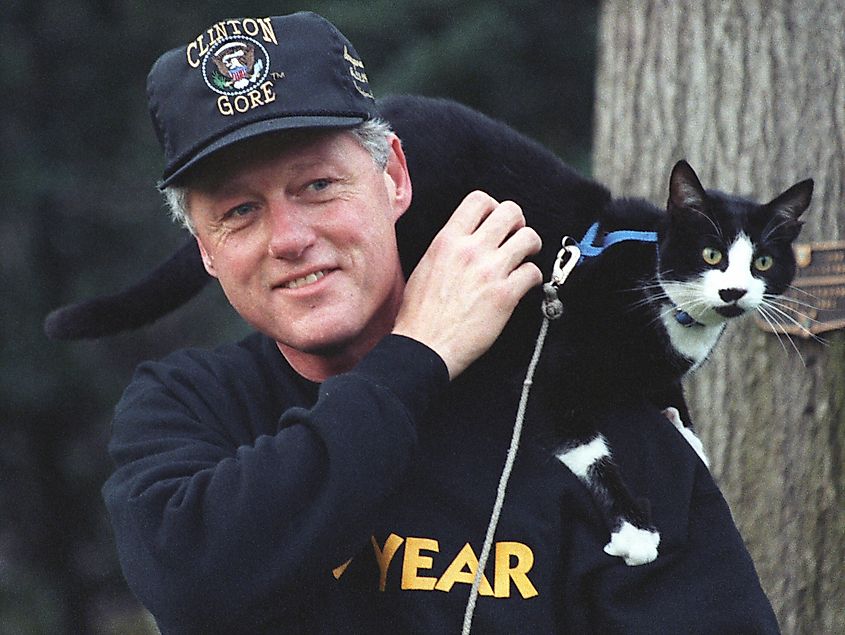

3. 1995-1996, 21 days

- President Bill Clinton

- Senate/House: Republican.

After a five-day lapse in November, a deeper fight followed over GOP plans to cut spending and reshape Medicare, education, and environmental programs. Clinton vetoed bills he said cut too far; Republicans threatened the debt ceiling. About 284,000 workers were furloughed; parks closed, research and toxic-waste cleanups halted, and passport and visa processing slowed. Arizona briefly reopened Grand Canyon using state resources to protect tourism. Polling largely blamed congressional Republicans, boosting Clinton before 1996. A January 6 compromise reopened government with modest restraint but without sweeping GOP cuts, and the showdown became the template for later shutdown brinkmanship. It also clarified shutdown playbooks across agencies for years.

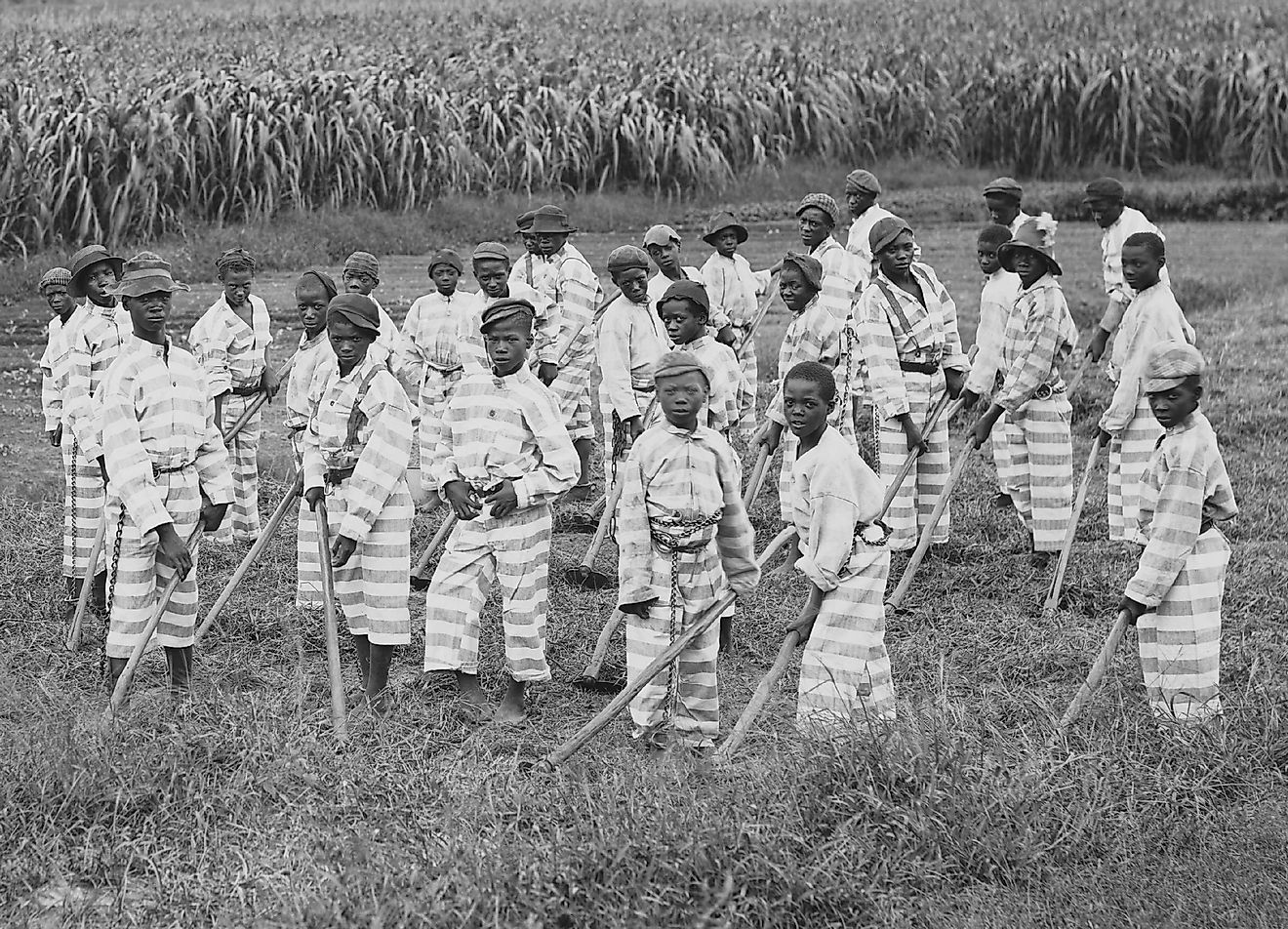

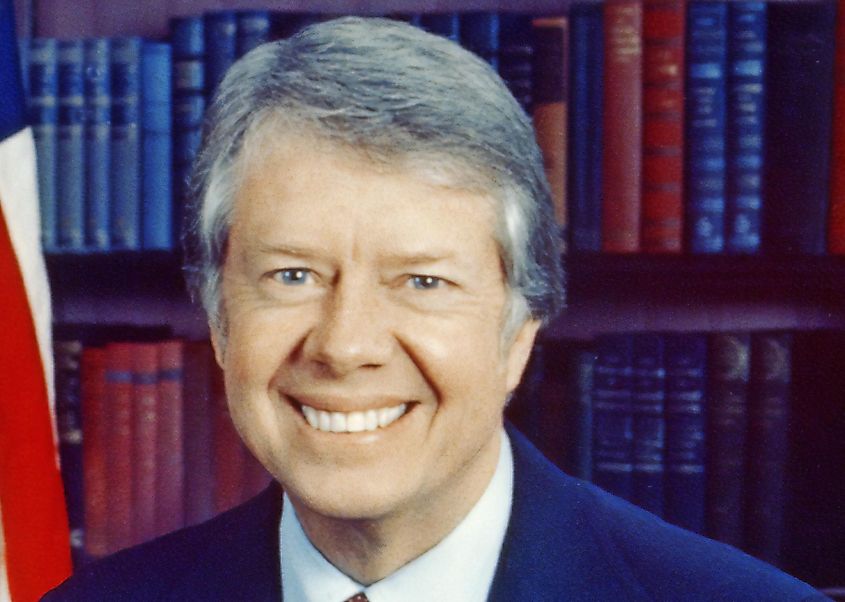

4. 1978, 17 days

- President Jimmy Carter

- Senate/House: Democratic.

Before 1980-81, opinions by Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti, agencies often continued operating during lapses. In 1978, negotiations over appropriations stalled for 17 days, but broad furloughs and closures typical after 1980 generally did not occur. Agencies minimized new obligations while keeping most functions running until Congress enacted new funding. The episode illustrates how pre-1980 funding gaps were long but less disruptive, and why the later legal guidance transformed lapses into true shutdowns. CRS notes several of the lengthiest gaps, eight to seventeen days, occurred in 1977-1980 before shutdown procedures were consistently followed nationwide. Both chambers were Democratic, and disputes centered on appropriations timing rather than policy changes.

5. 2013, 16 days

- President Barack Obama

- Senate: Democratic; House: Republican.

The lapse began on October 1, 2013, when House Republicans tied funding to delaying or defunding the Affordable Care Act; the Senate and Obama refused. Roughly 800,000 workers were furloughed, while 1.3 million worked without timely pay. National parks and museums closed; immigration and civil-rights cases slowed. Standard & Poor’s estimated about $24 billion in lost output. The shutdown ended on October 17 when Congress passed the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2014, reopening the government and suspending the debt ceiling temporarily. The episode foreshadowed later fights over healthcare and proved that shutdowns raise costs without resolving core disputes. Polls showed Republicans bore more blame, shaping leadership choices in subsequent budget standoffs and negotiations.

Why Shutdowns Persist

Congress controls the purse; presidents can veto; and neither side is obliged to fold. Since Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti’s 1980-81 opinions, agencies must halt most work when appropriations lapse, with narrow "life and property" exceptions. That clarity has raised the stakes of budget brinkmanship. The lessons from the longest episodes are consistent. First, the economic math is perverse: shutdowns cost more than keeping government open, once you count contingency plans, lost user fees, and guaranteed back pay. Second, the public’s patience is finite, and blame is rarely distributed evenly. Third, while shutdowns can extract concessions, they seldom settle the underlying policy disputes, which return in the next appropriation cycle.

So the real question isn’t whether shutdowns "work." It’s whether a system that periodically withholds basic public goods to resolve high-stakes policy disputes is one Americans are still willing to tolerate, and if not, which reform (automatic continuing resolutions, stricter debt-limit rules, or something else) they’ll demand next.