The 1977 Ground Blizzard That Buried New York Without Falling Snow

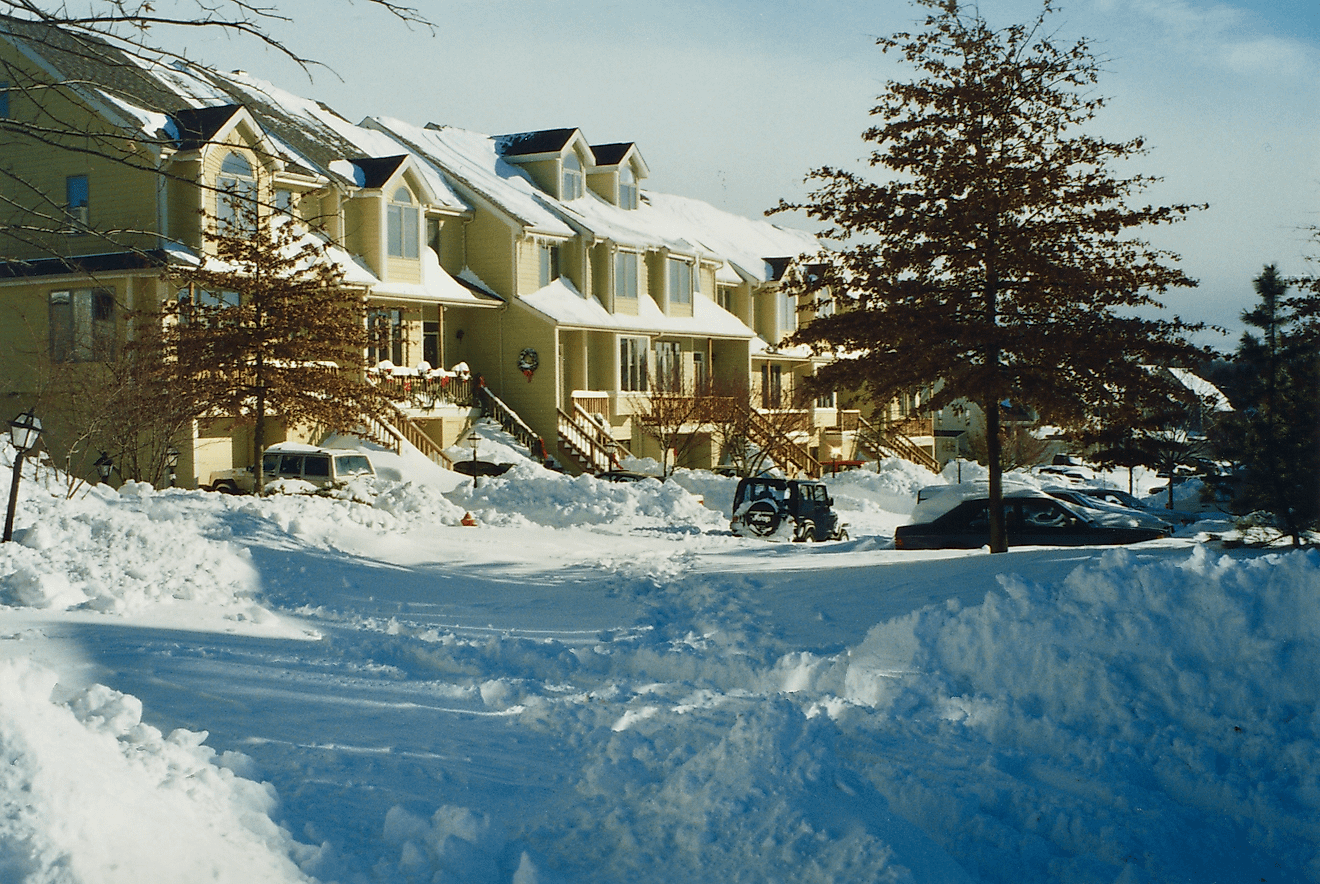

In late January 1977, New York was buried by a blizzard that barely needed fresh snowfall to become historic, and it killed at least 29 people. From January 28 to February 1, near-hurricane-strength wind gusts tore across Western, Central, and Northern New York, as well as Southern Ontario, turning the region into a frozen whiteout.

In Buffalo, the National Weather Service recorded gusts as high as 69 mph, while snow already on the ground, especially the powder sitting on frozen Lake Erie, became the real fuel for disaster. With the lake sealed over since mid-December, the usual lake-effect snowmachine shut down, but a deep layer of loose snow remained ready to be launched.

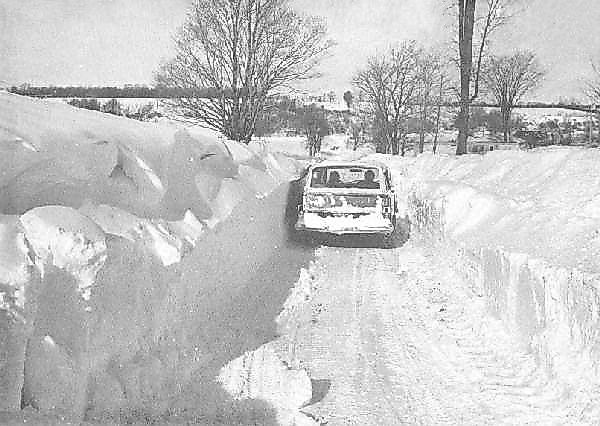

When the winds arrived, they blasted that powder across about 6,200 square miles, packing it into 20 to 40-foot drifts that swallowed roads, cars, and bus stops. Entire towns were cut off, plows became useless, and in the hardest-hit areas, snowmobiles were the only way to move. This is the story of the “ground blizzard” and how Lake Erie freezing over helped create it, and how far the chaos spread from Buffalo into Southern Ontario and Northern New York.

The Brutal Winter of 1976-77

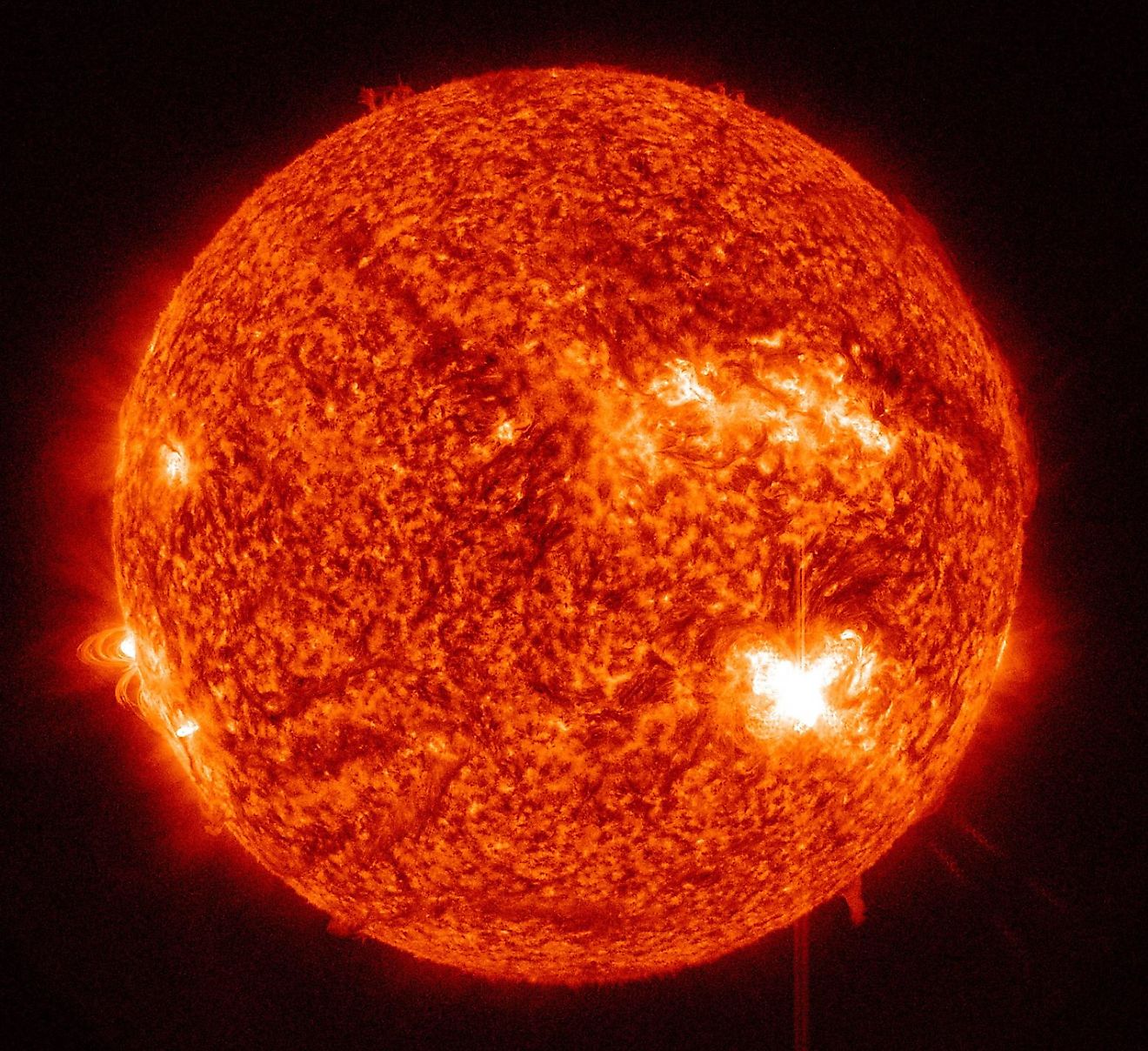

A rare and persistent atmospheric setup helped set the stage for the 1977 blizzard. From October 1976 through January 1977, a strong ridge over western North America and a deep trough over the east locked into place, creating an extreme jet stream pattern. A blocking high over the Arctic pushed the polar vortex unusually far south into Canada, sending repeated blasts of Arctic air into the central and eastern U.S. This produced record cold, with the Ohio Valley averaging more than 8°F below normal. Snow even reached Miami and the Bahamas, while Alaska was unusually warm and the Pacific Northwest suffered record drought.

Western New York

The Storm

Months of unusual weather set Buffalo up for disaster before the Blizzard of 1977 even began. Summer and early fall were wetter than average, then winter arrived early: Buffalo logged its first snow trace on October 9 and accumulating snow by October 21, with multiple lake-effect bursts piling up totals across western New York. Lake Erie was unusually cold by the end of October and, after a bitter November, the coldest in Buffalo in nearly a century, snowfall surged. Late November brought heavy dumps, and December stayed brutally cold and snowy, pushing snow depth past two feet at times. By December 14, Lake Erie had frozen over in a record-early freeze, shutting down typical lake-effect moisture but leaving vast snow cover locked in place.

January turned extreme. Buffalo recorded its coldest January on record, never reaching freezing, while snowfall continued almost daily after Christmas. By January 27, nearly 150 inches of snow had already fallen that season, leaving roughly three feet on the ground, and the city was already strained: power companies warned of snow-laden lines, energy shortages forced closures, and snowplows struggled with abandoned cars and frequent breakdowns. A "Snow Blitz" ticketing-and-towing push helped, but side streets remained nearly impassable.

Then the blizzard hit on Friday, January 28, as an Arctic front swept east. Buffalo issued its first-ever blizzard warning, and a "white wall" of snow and wind swallowed the city around midday. Visibility dropped to zero, winds gusted near 69 mph, temperatures plunged, and drifts rose to 15-25+ feet in places, much of it blown from the powdery snow sitting on frozen Lake Erie. Roads became impassable within minutes, stranded planes froze in place, and pedestrians formed human chains to reach shelter.

By Friday night, thousands were trapped downtown, emergency responders relied on snowmobiles and four-wheel drives, and looting and fires complicated rescue efforts. Over the next week, travel bans, National Guard deployments, federal emergency declarations, and "Operation Snow Go 1977" drove the cleanup. A brief improvement was followed by renewed drifting on February 3, extending closures until roads cleared and temperatures finally rose above freezing on February 9.

The Aftermath

The Blizzard of 1977 created massive, rock-hard snowdrifts, up to 30 feet high, because extreme winds packed the snow so tightly that regular plows became useless. Crews relied on heavy equipment like front-end loaders and even trenching machines to free trapped residents. Widespread travel bans were declared, and a huge response followed: the Army Corps hired private contractors, while the National Guard, Army, Marines, and Air Force supported rescues and medical transport. Relief groups fed tens of thousands using snowmobiles. Despite only about 12 inches of new snow in Buffalo, winds blew existing snow from frozen Lake Erie into deadly whiteouts. In all, at least 29 people were killed by the storm across New York and Southern Ontario, and the economic losses ran into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Southern Ontario

The Blizzard of 1977 hammered Southern Ontario's Niagara Peninsula, with the worst destruction concentrated right along the Lake Erie shoreline. Communities such as Fort Erie, Port Colborne, and Wainfleet were hit hardest, while conditions improved just a mile or two inland. Like western New York, the region already had heavy snowfall before the storm, Port Colborne and Fort Erie had accumulated more than a meter since Christmas, providing loose snow that the winds could weaponize.

Late morning on January 28, fierce winds surged to 70 km/h with gusts up to 100-120 km/h, creating whiteout visibility and piling snow into towering drifts that trapped cars, closed roads, and forced people to abandon vehicles. Hundreds were stranded in factories, and roughly 2,000 students across the Niagara region spent nights stuck in schools as drifts and stalled buses made travel impossible. In the hardest-hit lakefront areas, windows shattered, doors collapsed, and power outages lasted up to 72 hours, leaving residents burning furniture for warmth.

Drifts reached staggering heights, reported up to 45 feet, with snowmobilers unknowingly riding over buried vehicles and even rooftops. Snowbanks lingered into June in some places. Snowmobiles became essential for police, medical transport, hydro crews, and food deliveries, supported by CB radios and local stations sharing emergency requests. The Canadian Forces and militia were deployed to rescue stranded motorists and reopen key highways. Farmers dumped milk and struggled to feed animals, while some residents remained snowed in for nearly three weeks. Other Ontario cities like London, Kitchener, Toronto, and Hamilton faced high winds and blowing snow, but nowhere matched the shoreline devastation.

Northern New York

Northern New York, especially Jefferson and Lewis counties, was slammed by the Blizzard of 1977 as the cold front arrived on January 28. Watertown quickly dropped to zero visibility, with winds peaking near 49 mph, and initial snowfall of 8-12 inches. But unlike frozen Lake Erie, unfrozen Lake Ontario fueled intense lake-effect snow bands, pushing storm totals to extreme levels, around 66 inches in Watertown, 93 inches at Fort Drum, and 100+ inches in nearby areas. Drifts reached 15 to 30 feet, stranding over 1,000 motorists and trapping workers, including 150 people at a Watertown factory.

Local radio became a lifeline as stranded announcers kept broadcasts running around the clock, while CB teams, the Red Cross, snowmobiles, and four-wheel drives coordinated help. After brief lulls, heavy snow and strong winds returned through January 31, dumping more than three feet of new snow in days. Although winds were lower than in western New York, drifting remained severe.

Jefferson and Lewis were added to the federal emergency declaration on February 1 and later named major disaster areas. Cleanup relied on contractors and military support, including the National Guard, Army units from Fort Drum, and Marines using tracked vehicles. Supply shortages forced a limited lifting of travel bans so stranded travelers could leave.

Agriculture suffered heavily: about 85% of Jefferson County dairy farmers dumped milk, contributing to major losses. At least five of the storm's 29 deaths occurred in northern New York, all heart attacks. Even after the storm ended, the massive snow depth and water content raised flooding concerns.