8 Must-See Historic Forts In Washington

Washington once guarded Puget Sound with a “Triangle of Fire,” a trio of forts that trained on disappearing guns and watched the waterways like hawks. These eight must-see historic forts in Washington feel larger than life. One stood sentry over Admiralty Inlet, another powered a fur-trade network that reached London and China. A few have been rebuilt so you can step straight into the 1800s, where costumed interpreters hammer iron, churn butter, and share frontier stories.

Think of them as history books you don’t just read, you wander. Climb the concrete batteries at Fort Casey, step inside the rebuilt stockade at Fort Vancouver, and stand in an 1850s blockhouse at Fort Simcoe. Each place opens a different doorway into the state’s past, shaped by defense, trade, and the people who lived, worked, and traveled along these shores and rivers.

Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver anchors the region’s fur-trade story on the north bank of the Columbia River. Founded in 1824-25 in Vancouver, it quickly grew into a trading powerhouse. Beaver pelts, salmon, and lumber left by the shipload, while goods from London and China flowed in. By the 1840s, the US Army had taken over, turning the post into a supply stop for families pushing west on the Oregon Trail.

The original wooden walls went up in flames in 1866, but today you can walk through a full reconstruction that brings the place back to life. Step inside the blacksmith shop and hear the clang of iron on iron, wander through tidy gardens, or peek into officers’ quarters furnished just as they were in the 1840s. Rangers sometimes appear in period dress, hammering, cooking, or swapping stories that make it feel less like a museum and more like a living village.

Outside the stockade, there’s more to explore: the historic Vancouver Barracks, the old Post Hospital, and an orchard that still produces fruit. Archaeological digs keep turning up the everyday objects left behind by soldiers, traders, families, and Native workers. Those finds and the exhibits run by the National Park Service make it clear this was never just a fur trade outpost. It was a crossroads of cultures, where Chinook and other Native peoples shaped daily life as much as any company clerk or Army officer.

Fort Columbia

Fort Columbia guards the mouth of the Columbia River from a hillside perch above Chinook Point. Between 1896 and 1904, the Army built Fort Columbia as one of three forts that kept enemy ships from slipping inland. The soldiers here drilled with “disappearing guns,” massive weapons mounted on concrete batteries that could rise, fire, and then drop safely out of sight.

The Army remained on site until 1947, and plenty of its presence lingers. Officer houses and barracks line the grounds, while underground magazines sit carved into the hillside, the air inside cool and damp. Walk the mossy tunnels, and it’s easy to imagine the thunder of practice drills and the uneasy quiet of scanning the river for threats that never came.

Today, the park balances military history with something much older. The Fort Columbia Interpretive Center explains how the defenses worked and highlights the Chinook Nation, whose people fished and traded here for centuries before the Army built over their village. Trails thread across the slope, leading to both the remnants of gun emplacements and wide-open views of the Columbia as it rolls into the Pacific. Now part of the Washington State Park system, Fort Columbia is open year-round, waiting for anyone curious enough to wander its mix of ruins, stories, and scenery.

Fort Casey

On the west side of Whidbey Island, Fort Casey was built as part of the “Triangle of Fire,” a defensive network designed to block enemy ships from entering Puget Sound. Builders broke ground in 1897, and by 1902, the fort bristled with heavy guns, including 10-inch disappearing cannons that could rise to fire and then sink safely back behind concrete walls. Working in concert with Fort Worden and Fort Flagler, the batteries created a lethal crossfire across Admiralty Inlet.

The guns never saw combat, but the fort served as a training ground through both world wars before closing in 1953. When Washington converted it into a state park in the 1960s, crews restored several of the weapons so visitors could get a sense of how they operated. Today, it’s easy to spend an afternoon climbing the staircases of Battery Worth, listening to your footsteps echo inside the cavernous gun chambers, or stepping into the Admiralty Head Lighthouse, which still keeps watch from the bluff.

From the top, the view stretches wide: ferries and freighters cutting across the channel, sailboats catching the wind, and on a clear day, the Olympic Mountains rising sharply on the horizon. You stand there and realize it’s part fortress, part lookout point, and one of the clearest reminders of how seriously the US once guarded these waters. And if you squint just right, you can almost picture the cannons tracking a phantom ship that never came.

Fort Worden

At Point Wilson in the seaside town of Port Townsend, the Army named the fort for Admiral John L. Worden, bristled it with more than 40 heavy guns, and even fielded balloon units for aerial observation. Opened in 1902, Fort Worden quickly became the command post for Puget Sound’s defenses. For decades, soldiers drilled along the bluffs, and the installation stayed active through both world wars before finally closing in 1953.

Today the site has a new life as Fort Worden State Park, stretching across more than 400 acres. The stately homes of Officers’ Row still line the parade ground, while historic buildings now house the Coast Artillery Museum and the Commanding Officer’s Quarters, each one offering a close look at early 20th-century military life. Trails lead down to long, driftwood-strewn beaches, and the Point Wilson Lighthouse, still active and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, stands as a bright landmark at the park's edge.

Exploring further, you’ll find hidden batteries tucked into grassy bluffs, echoing concrete chambers where cannons once stood guard, and barracks now hosting everything from music festivals to writing workshops. For the Jamestown S’Klallam and Port Gamble S’Klallam peoples, though, this ground holds much deeper meaning. It is the same shoreline where they fished and camped for centuries before the first gun was mounted. At Fort Worden, layers of history overlap, military and cultural, making the landscape feel alive with stories from every era. Stick around long enough and you’ll probably hear a few of those stories shared in person.

Fort Flagler

Fort Flagler, perched on Marrowstone Island, was built in 1899 to complete the Triangle of Fire with Casey and Worden. Its 26 mounted guns once swept Admiralty Inlet, creating a deadly crossfire that made sneaking into Puget Sound nearly impossible for enemy ships. During both world wars, soldiers trained on anti-aircraft weapons here, manned the batteries, and patrolled the waters just offshore.

The Army finally shut it down in 1953, and Washington turned the grounds into a state park. Much of the old infrastructure is still in place. You can walk through Battery Wansboro, step into the officer quarters and barracks, or stand on the wide parade ground where companies of soldiers once drilled. Trails loop around the headlands, gulls wheel above, and the salt wind lashes the concrete gun pits, bringing the fort’s abandoned defenses to life differently.

Many visitors camp right on the beaches, then spend the day wandering through the tangle of concrete passages built into the hillsides. Interpretive programs and seasonal tours explain how the fort worked and why it mattered. And woven through it all is a much older story. Coast Salish tribes once foraged, fished, and gathered along these same shores. That mix of natural beauty, layered history, and cultural legacy makes Fort Flagler so memorable.

Fort Simcoe

Fort Simcoe preserves one of Washington’s clearest windows into the 1850s frontier. In 1856, during the Yakama Wars, the US Army built Fort Simcoe on Yakama tribal land at White Swan as an outpost. The Army abandoned it after only three years, but the Bureau of Indian Affairs kept the grounds active by converting them into a school for Native children.

What sets Fort Simcoe apart today is how much of it still stands. Five original buildings from the 1850s survive, officers’ quarters, a commissary, a hospital, and a blockhouse among them. These weathered wooden structures rank among the oldest Army buildings left in Washington, and walking past them feels like stepping straight onto a mid-19th-century frontier post.

Now preserved as Fort Simcoe Historical State Park, the site mixes history with open landscapes. Visitors can explore the furnished commandant’s house, cross the shaded parade ground, or wander oak groves where Lewis’s woodpeckers make their nests. Interpretive signs and programs connect the story of the Yakama Nation to the events that unfolded here, reminding you that this place was never just about military strategy. Spending an afternoon here feels less like a museum stop and more like paging through a well-worn family album, except the family story belongs to an entire valley.

Fort Nisqually

Inside Point Defiance Park in Tacoma, Fort Nisqually began in 1833 as a fur trading post built by the Hudson’s Bay Company. It later became the hub of the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, raising livestock and crops that kept the trade flowing. For a time, it was one of the most important posts in the region. Eventually, the US government ordered its closure, and modern development erased the original site.

In the 1930s, two original buildings, the Granary and the Factor’s House, were moved into the park. With help from the Works Progress Administration, stockade walls and additional structures were reconstructed, creating what is now the Fort Nisqually Living History Museum.

Step through the gates and the 1850s come alive. Costumed interpreters churn butter, hammer in the blacksmith shop, and tend gardens planted with heritage crops once grown here. Seasonal festivals like the Brigade Encampment invite visitors to try their hand at old trades and crafts. The result feels less like a static exhibit and more like walking into a working post, the kind where Coast Salish families and Hudson’s Bay clerks once haggled over furs, food, and goods. And if you hang around the interpreters long enough, you might find yourself swept into a story or even recruited for a quick chore. Few places in Washington capture the daily rhythm of frontier trade as vividly as Fort Nisqually.

Fort Okanogan

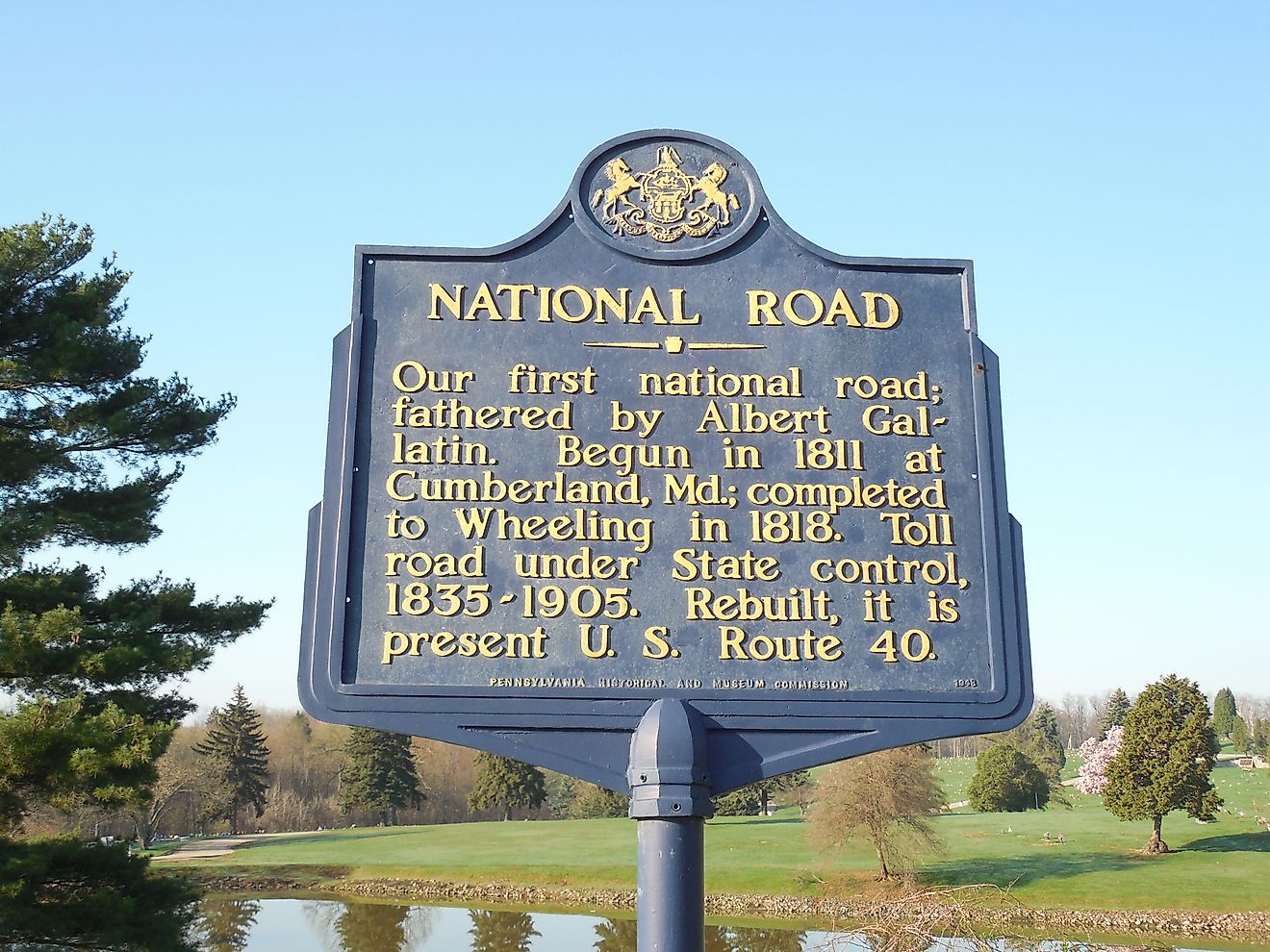

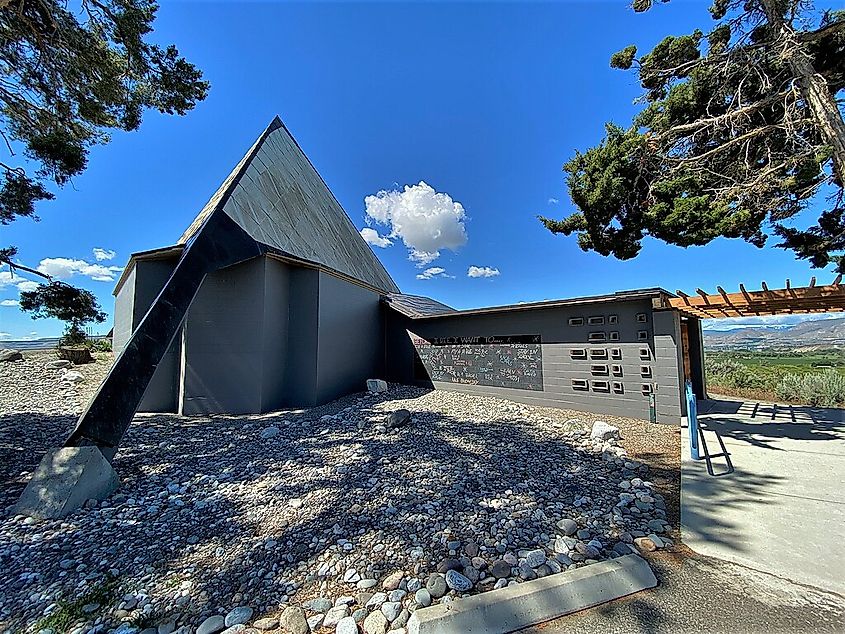

Near the town of Brewster in north-central Washington, Fort Okanogan traces its beginnings to 1811, when the Pacific Fur Company set up an outpost at the meeting of the Okanogan and Columbia rivers. It later passed to the North West Company and eventually the Hudson’s Bay Company, each using it as a foothold for trade in the interior Northwest. For decades, the fort became a gathering ground where Plateau tribes and European traders met to exchange salmon, furs, horses, and manufactured goods.

The post closed around 1860, and none of the original wooden buildings remain today. A century later, in 1960, Washington built the Fort Okanogan Interpretive Center, a distinctive triangular-roofed structure perched above the river confluence. Inside, exhibits explore fur trade life, with displays about John Jacob Astor’s Astorians and a large mural depicting how the fort once looked. Outside, trails with interpretive signs lead to viewpoints over the land where the posts originally stood.

Today, the site belongs to the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, and the story told here reflects both Native and trader perspectives. Open during the summer season, the interpretive center offers one of the few chances to step into the story of Washington’s very first fur trading post.

Where History Lives On

Washington’s forts tell the state’s story from every angle. At Fort Vancouver, the fur trade stretched this corner of the continent into a global network. Fort Simcoe’s blockhouses still stand as reminders of the 1850s frontier. The “Triangle of Fire,” made up of Casey, Worden, and Flagler, shows just how seriously the US once guarded Puget Sound. And at Fort Nisqually and Fort Okanogan, reconstructions and interpretive centers pull you straight back into the fur trade era.

Each site layers military history with Native history and community life, often in the same footprint. Walk through them today, and you’re not just touring old defenses or trading posts. You’re standing where families lived, where cultures met, and where the shape of Washington’s past was hammered out on the ground beneath your feet. And maybe that’s the best part: these forts aren’t just frozen relics, they’re places where the past still whispers if you take the time to listen.