What Was The Crisis Of The Third Century?

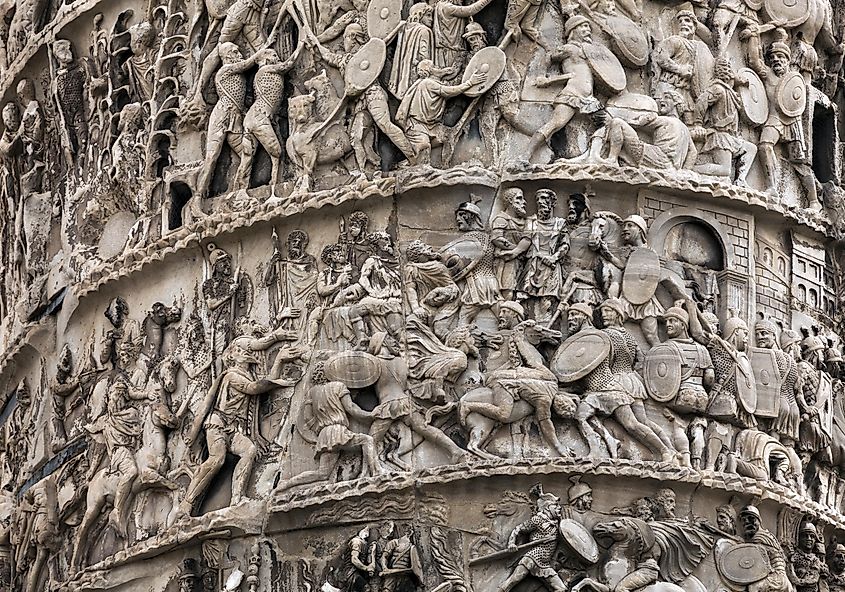

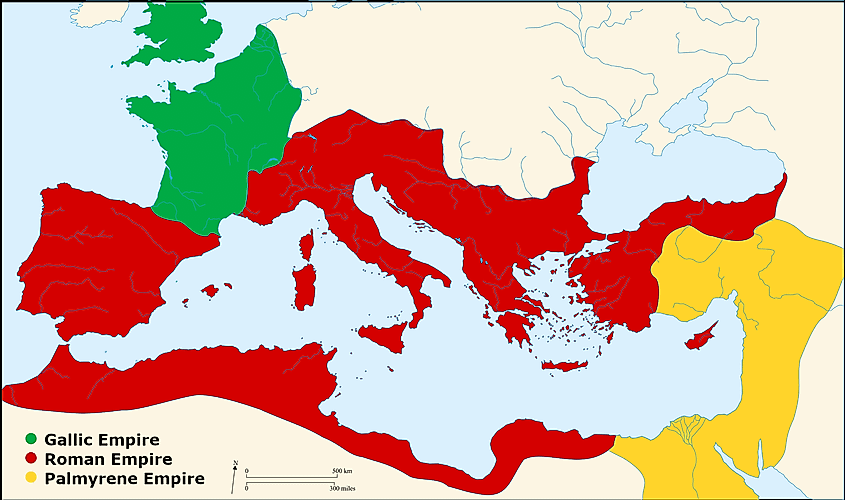

The Crisis of the Third Century resulted in the near collapse of the Roman Empire. During these 49 years (also commonly referred to as the Imperial Crisis, 235-284 AD), the Roman Empire saw more than 25 emperors, and it temporarily split into three political states: the original Roman Empire, the Gallic Empire, and the Palmyrene Empire.

Without the unity of centralized power, chaos broke out throughout the Empire— military coups became a tradition, plagues ravaged the population, and invasion and civil war caused destruction in major cities. Discover here how, after nearly half a century, the Empire managed to salvage its fate.

Causes of the Crisis of the Third Century

Although many factors led up to the Crisis of the Third Century, inflation, political turmoil, and lack of respect for Emperor Alexander Serverous are arguably the most prominent. The inflationary problems experienced during this period trace back to Emperor Septimus Severus (193-211 AD), who attempted to buy loyalty from the military by raising wages. This decision, however, required Septimus to devalue the Empire's coinage to increase coin production, resulting in inflation that citizens particularly felt during the reign of Alexander in later years.

On top of this inflationary turmoil, the Roman Empire's territory had spread too far and thin, and it could not manage its provinces effectively. Under this overextension, existing provinces continued subdividing, causing rising bureaucratic costs and taxes. Tax collection became ever more difficult due to failing administrative structures and corruption. Complemented by fears of the plague, these factors caused the Roman Empire to dive into a period of political, social, and economic uncertainty.

When Alexander Severus came to power, he implemented policies generally viewed as initially promising, such as seeking a higher degree of participation from the senate and receiving council from experienced administrators. However, it was well known that Alexander was under the control of his mother, whom the Roman public shared no fondness for, resulting in the military losing respect for him. Germanic tribes threatened the Roman Empire during this time, and in 234 AD, Alexander took his mother's advice by planning to buy off the aggressors to avoid engaging in battle. This decision was met with extreme disdain and disapproval by his troops, who then decided to assassinate both him and his mother. The Empire soldiers then selected Maximinus Thrax, a low-level career soldier, to become the new Emperor. This military coup effectively enflamed the Crisis of the Third Century.

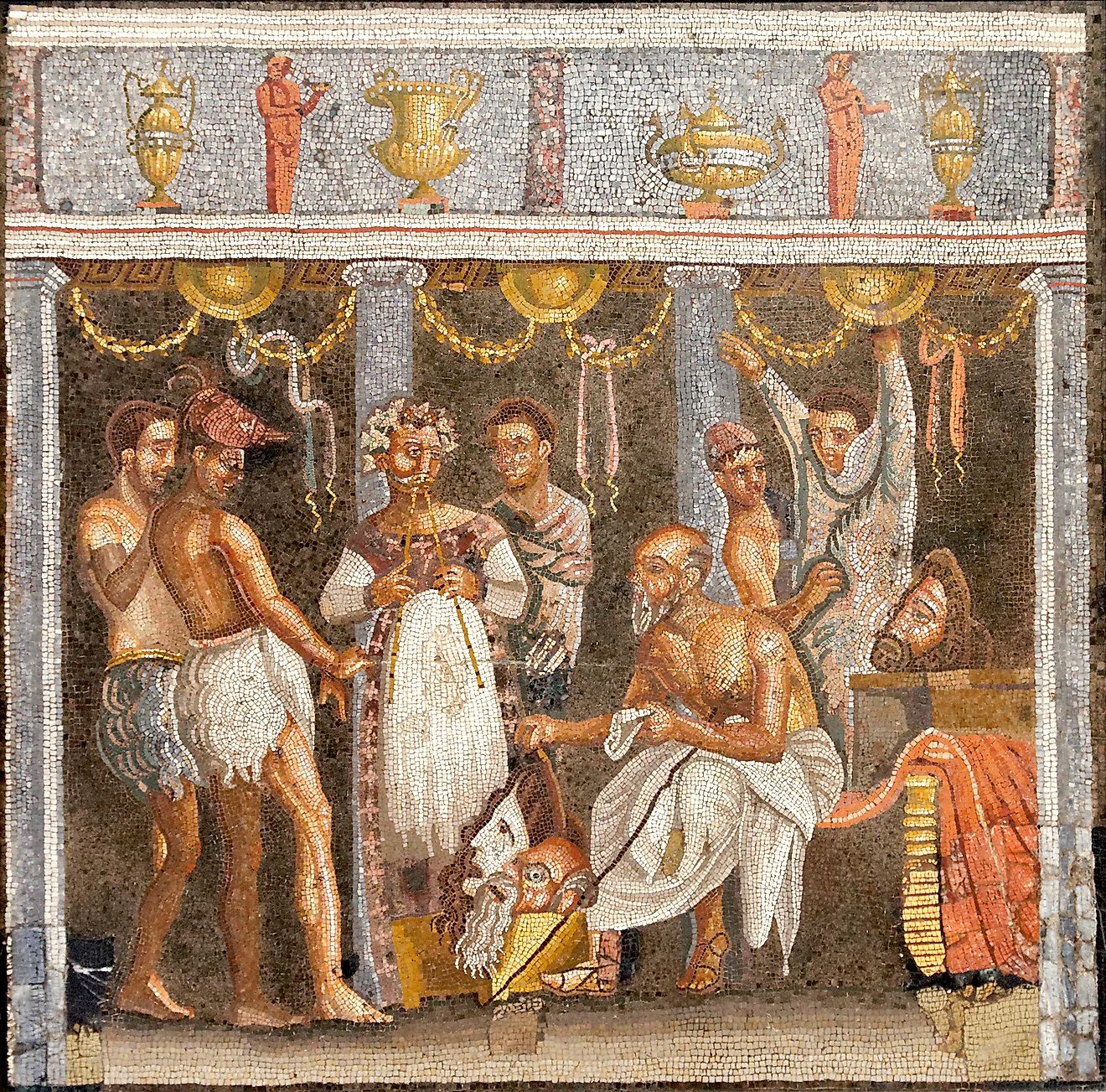

The Period of the Barracks Emperors

The military election of Maximinus Thrax as Emperor signaled the beginning of the period of the "Barracks Emperors," which refers to the more than 20 emperors elected by the army. These emperors often served short terms, frequently ending with their assassinations by their troops, who would later become unhappy with their rulings. Maximus Thrax served only three years (235-238 AD) when his troops killed him after tiring of constant bloodshed and warfare.

Following Thrax, some of the notable emperors during this period include: Decius (249-251 AD), who was known for his aggressive persecution against Christians; Gallienus (253-268 AD), who was a productive leader due to the reforms he enacted in the military; and lastly Aurelian (270-275 AD), who reunified the Roman Empire.

The Gallic Empire (260-274 AD)

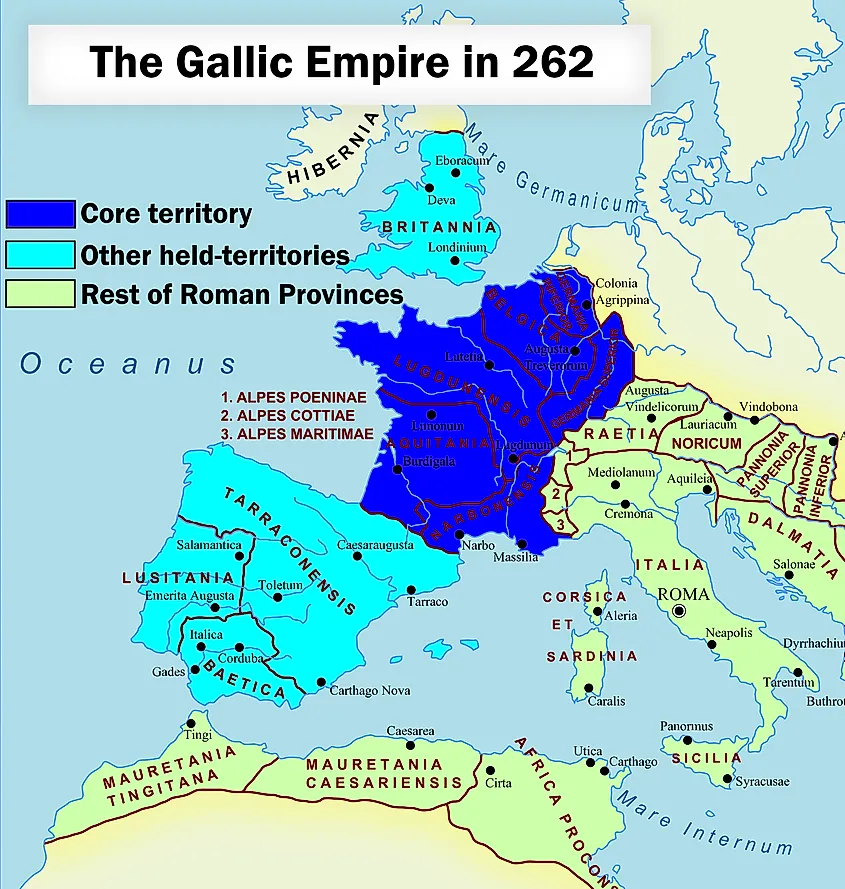

In 260 AD, Regional Governer Postumus split off to create the Gallic Empire, composed of Britania, Hispania, Gual, & Germania. Postumus founded the Empire to protect the region from external threats, as a catastrophe in the years prior caused the foreign Sassanian Army to nearly take control. Gallenius, the reigning Roman Emperor at the time, considered Postumus to be usurping territory from the Roman Empire and thus declared war.

However, with the simultaneous creation of the Palmyrene Empire and other ongoing crises, Gallenius was forced to treat the Gallic Empire as legitimate. It is important to note that Postumus never intended to be an enemy of the Roman Empire. Although Postumus did create a separate senate and government system, he attempted to maintain diplomatic relations with the Roman Empire while making policies. Postumus was assassinated in 269 AD by his troops, and Tetricus I would become the second reigning leader.

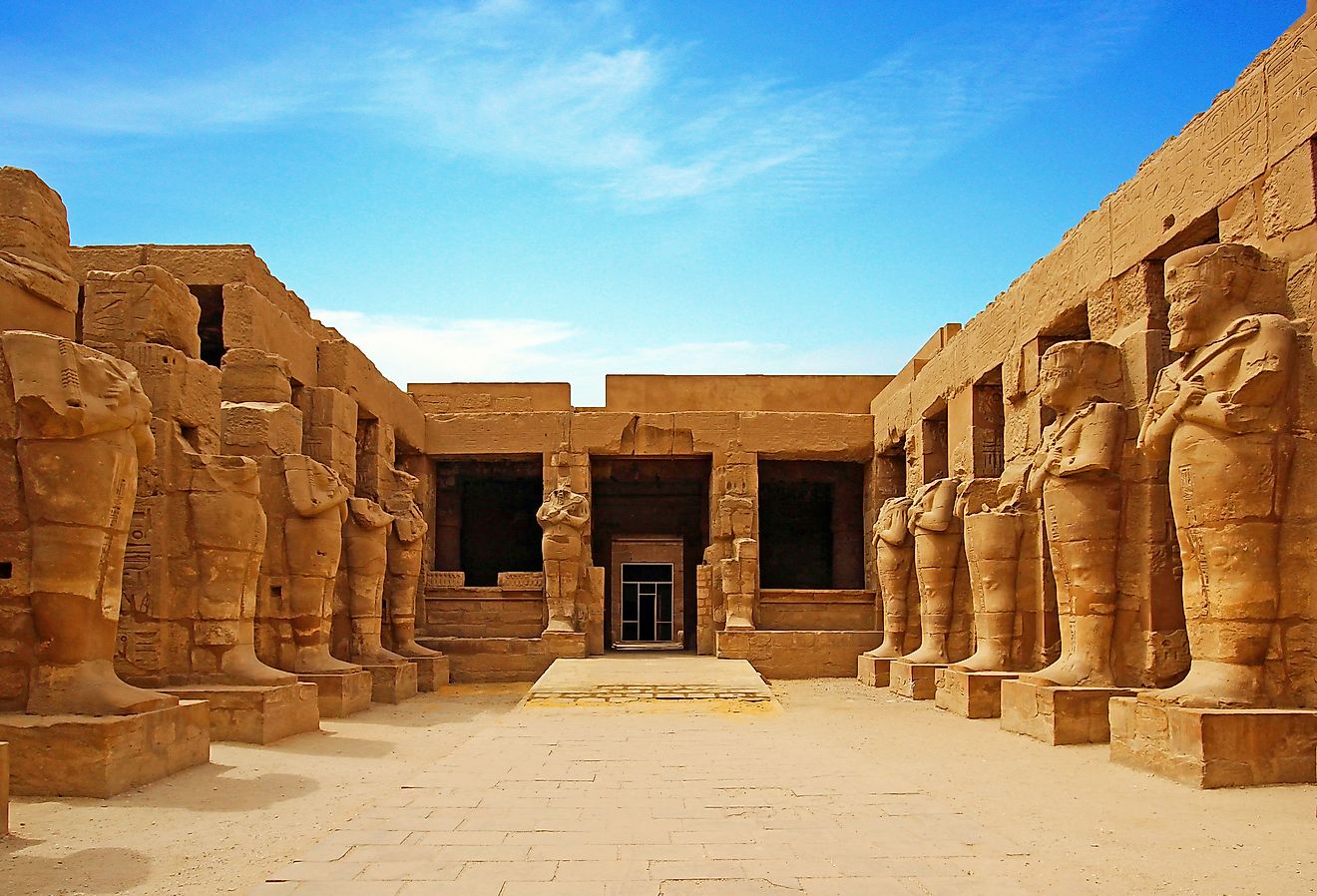

The Palmyrene Empire (267-272 AD)

Queen Zenobia of Palmyra created the Palmyrene Empire in 267 AD, which was composed of Syria, Palaestina, Arabia Patraea, Egypt, and parts of Asia Minor. Similarly to Postumus, Zenobia appeared to have intentions of maintaining amicable relationships with the Roman Empire. Queen Zenobia even had coinage made with the face of the current Roman Emperor Aurelian printed on it. However, Aurelian was not interested in conceding territory despite these gestures and began planning to retake both empires.

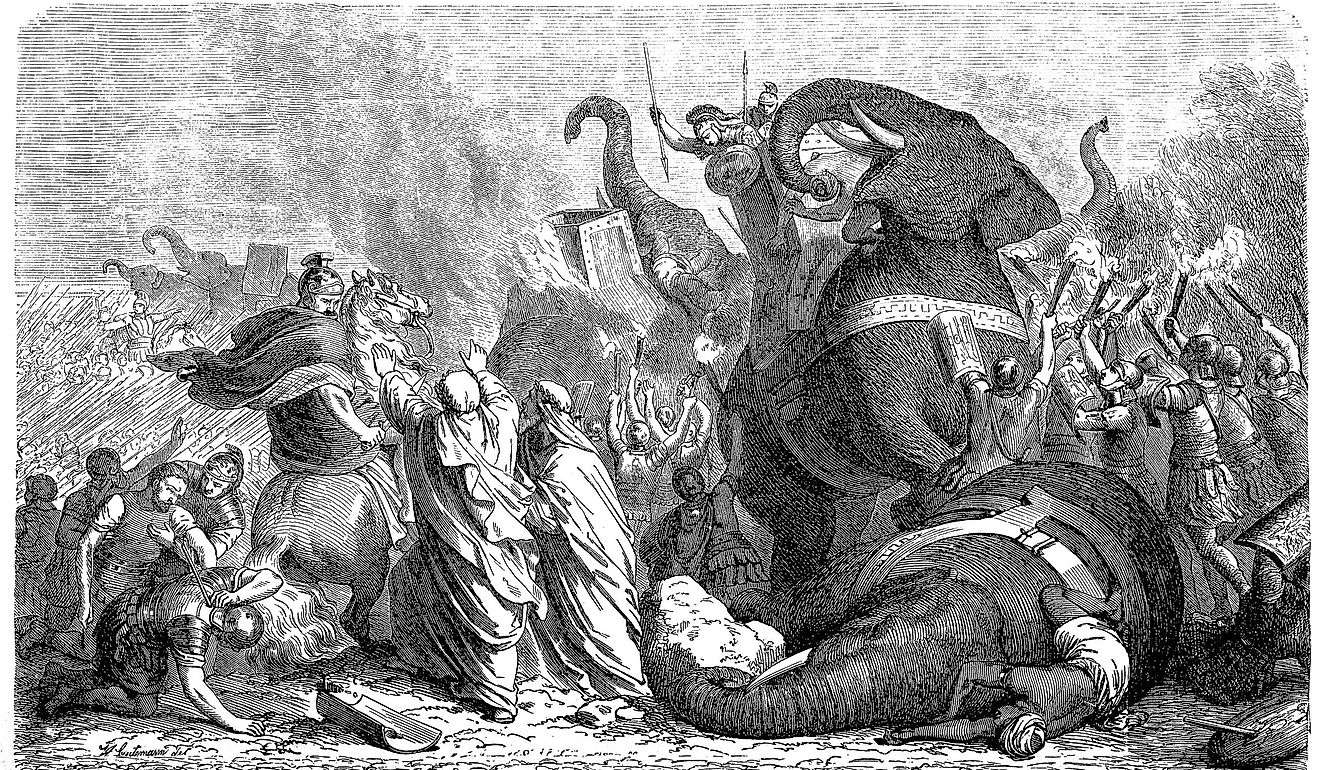

Reunification of the Roman Empire

In 272 AD, Emperor Aurelian (270-275 AD) initiated a number of battles against the Palmyrene Empire, eventually leading to the capture of Queen Zenobia and the reacquisition of the territory. Shortly after, Aurelian and his army would turn towards the Gallic Empire and defeat the Gallic Army in a battle known as the Battle of Chalons. Tetricus I and his son surrendered to Aurelian, causing the Gallic Empire to be officially reabsorbed by the Roman Empire. After having reunified the empires, Aurelian was assassinated in 275 AD by a group of his officers who, as one account suggests, had been misled to believe that Aurelian was planning to execute them.

Diocletian's Reform

While there were several more Barracks Emperors after Aurelian, the end of the Crisis of the Third Century finally arrived when Diocletian was named Emperor. During Diocletian's reign (284-305 AD), he reinstated an era of stability by decreasing the power of the military, stabilizing the currency to cut inflation, and implementing a new state of government known as the tetrarchy. The tetrarchy divided the Empire under the control of two separate senior rulers (Augusti), assisted by junior rulers (Ceasars) who would be the future successors, limiting possibilities of civil war and anarchy. Under Diocletian's system, the Empire was also divided into the Eastern and Western Roman Empires, making for more effective administration across the entire realm.

Final Thoughts

While Diocletian's Tetrarchy system ultimately did not last, it played a pivotal role in ending the Crisis of the Third Century. His contributions, accompanied by Aurelian's earlier actions to reunify the Roman Empire into one, allowed the Empire to enter into a period of political and economic relief and stability. Thanks to this restabilization, the Roman Empire was able to march on for another two centuries.