Did Emperor Nero Really Kill His Mother?

According to numerous historians and scholars, Nero, the last of the Julio-Claudian emperors, led a reign of terror and unparalleled debauchery. Of all his terrible acts, one stands out above the rest for its depravity and heinousness: the killing of his mother, Agrippina. This incident and others have been scrutinized in academic circles for possibly being a fabrication devised to denigrate this dynastic line. Some posthumous works paint Nero in an even more illuminating light.

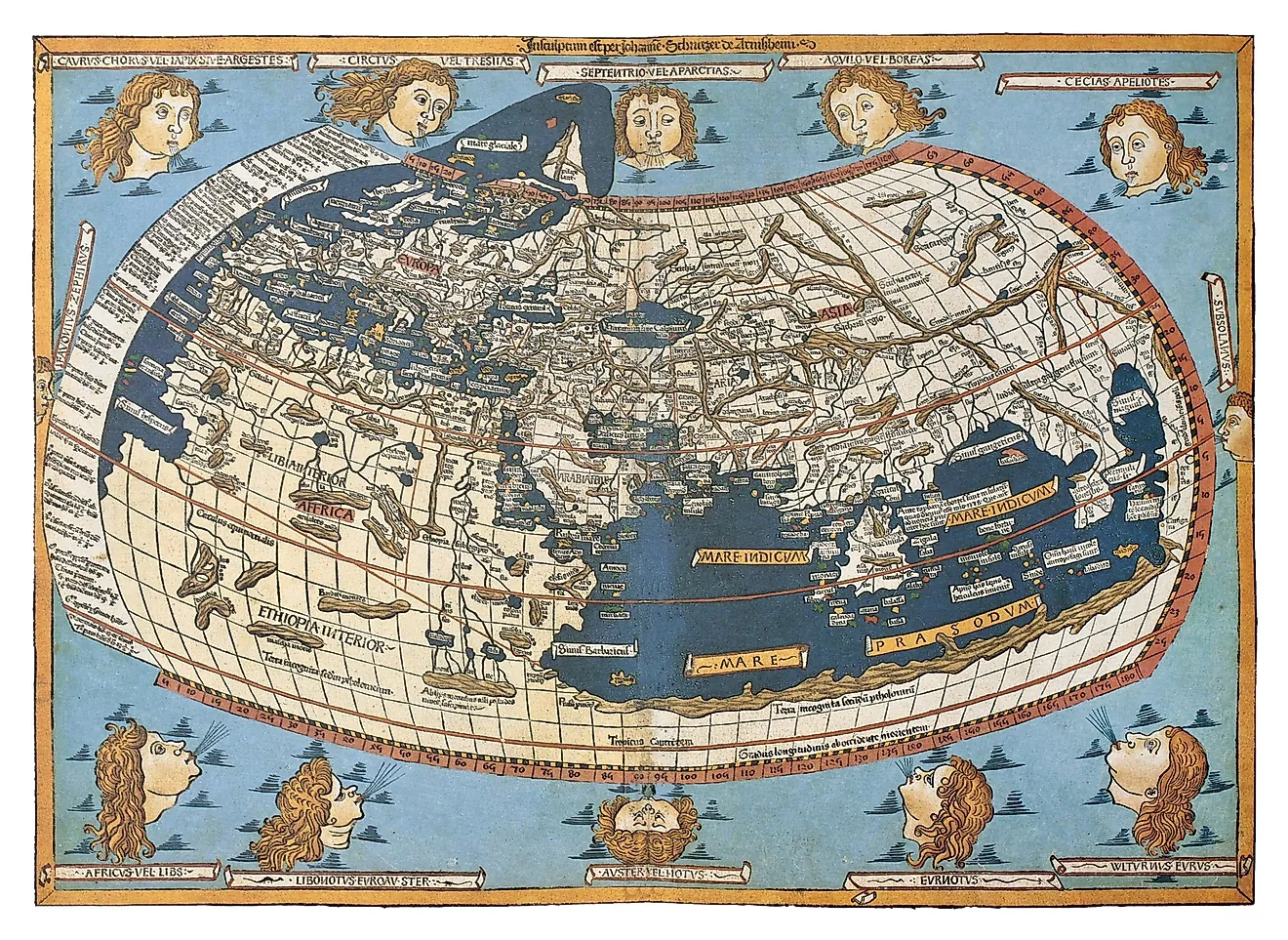

The early 15th-century Boucicaut Master of Manuscript Illumination in Paris depicts the young Emperor, who, after several failed attempts at murdering Agrippina, orders a soldier to kill her. Showing no signs of remorse, Nero examined and caressed his mother's lifeless body, and then, while others wept, he asked for a glass of wine. But are these tropes based on fact or biased? Some have argued that many stories involving Nero are false, such as when he "fiddled while Rome burned" because fiddles did not exist until the sixteenth century.

The Road to Becoming an Emperor

Nero, born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, reigned from AD 54 to AD 68. He was the fifth Roman emperor and the last from the Julio-Claudian line. Nero's father died when he was three, and his mother, Julia Agrippina the Younger, married her uncle, Emperor Claudius, when Nero was only 11. Agrippina convinced Claudius to adopt Nero for succession to power over his biological son, Britannicus. Claudius died in AD 54 amid rumors that Agrippina poisoned him, and Nero took the reins of the Roman Empire at 17.

Nero started his reign as a respected and fair ruler who disliked signing death sentences, starkly contrasting with his predecessor's iron fist. Most biographers attribute positive aspects, such as clemency, to the young ruler's reign until AD 59. However, it is commonly accepted that this is the year that his 35-month reign of terror began, beginning with his mother's reign. He would do the same to his wife, Ottavia, in AD 62.

Nero's Profligacy

Megalomaniacal acts and artistic delusions define Nero's reign after AD 59. He fancied himself a poet, ascetic, and actor at different times. Nero is also viewed as one who does not take responsibility for his gruesome acts, including the killing of his mother, which he blamed on suicide, and the burning of Rome in AD 64. Nero's role in the Great Fire of Rome is debated because he was in his Antium villa 35 miles away when the conflagration started. However, Romans believed Nero started the fire to propagate his aesthetic tastes. He passed the blame to the Christians, which inadvertently initiated the Roman practice of persecuting them.

Possibly Biased Oral Histories About Agrippa's Death

Even if Nero was not responsible for some of his heinous acts, he did not deny them, which could have been for political gain. This theory is underscored by the Roman courtroom rhetorical tradition of vituperation, which meant a political opponent could say anything they wanted about a rival, and the court would acknowledge it. Most of what is known about Nero was passed down by three historians: Tacitus, who considered him excessive; Cassius Dio, describing Nero as a womanizer and murderer; and Suetonius, who focused on the Emperor's many vices.

Modern scholars theorize that many of these accounts heed a literary style taught in Roman rhetorical schools. Tacitus' and Dio's versions of the Great Fire detail citizens wailing and mothers running with babies in arms, reminiscent of the city of Troy and other great ransacked cities. As with many ancient histories, tales about Nero were colored by personal and political biases, mainly when they could shed a cynical light on the Roman Empire.

Agrippina's Death

There is little doubt that Agrippina had political ambitions and an unquenchable thirst for power. Her web of influence spread large and far and led to the death of her son, who wanted to flee from her ambition and influence. Her opposition to Nero's courtship with Poppaea Sabina was the final catalyst. The empress was married to Otho, the future Emperor, when she and Nero started their affair. She would go on to be Nero's second wife and an opponent of Agrippina. Agrippina viewed Poppaea as a threat to her influence and a rival for Nero's affections.

Murdering Agrippina needed to be done covertly because she was the daughter of the notable General Germanicus. No loyal soldier would entertain dispatching a respected general's daughter. However, Agrippina had left many enemies in her wake, many of them with murderous intent toward her, and Nero used this fact to his advantage, one of his signature trademarks.

Failed Attempts

The stories about Agrippina's death are well-known, but some of the accounts border on farcical. Suetonius said Nero tried three times to poison his mother but abandoned the plan when he discovered Agrippina had protected herself by taking antidotes.

According to Tacitus, his second attempt at her life was his most creative and included the prefect of the imperial fleet at Misenum. Nero devised an imaginative idea to set his mother off in a self-destructing boat that would eject her into the water. Dio concurred that this plot was dreamed up by Nero and Seneca, who wanted to divert attention from their critics. His subterfuge went so far as to invite his mother to Quinquatrus for the festival of Minerva to draw her away from Rome.

Agrippina arrived and was taken by Nero to a villa. Rumor has it that she became suspicious and traveled to the villa by land. However, she calmed her nerves because Nero convinced her to embark on the rigged boat to the Bay of Naples. During the voyage, the canopy above Agrippina collapsed, but it failed to kill her. The ship also failed to disintegrate. A woman named Acerronia convinced the crew that she was Agrippina, and they beat her to death while Agrippina swam for shore. However, she came to her demise in AD 59 at the orders of Nero, who blamed her death on suicide. This account follows Nero's narrative of blaming someone or something else for his evil deeds.

Biased Histories

Many scholars point to the fact that Tacitus and Suetonius were senators opposed to the imperial system that Nero represented. Although a senator, Cassius was more conservative than the other historians and often criticized Nero's practices. For instance, Tacitus describes Nero killing his pregnant wife, Poppaea, by kicking her in the stomach. He also accused a young Nero of poisoning Britanicus when he was 13 by adding an odorless, colorless poison to a jug of water, which had a deadly effect within seconds of ingestion.

Tacitus was also the driving force behind the story of Nero burning Rome. Meanwhile, Suetonius frequently referenced Nero's flamboyancy and detailed accounts about him wandering the Roman streets in disguise, stabbing people, and throwing their bodies into the sewers. He also claims that Nero loved his audience and made at least 5,000 Romans applaud while he performed.

Contrary to these accounts, modern archaeological evidence from Pompeii suggests Nero was popular among ordinary people. It is reasonable to assume that some of the stories about Nero are false, but this fact does not reduce his role in other heinous acts.

Nero's atrocities are widely known, but his oral history is attributed to historians who had an agenda. This does not imply that Nero was not violent or even a megalomaniac. Still, when studying the atrocious events linked to him, they should be reviewed in the context of his environment.