9 Archaeological Finds Scientists Still Can't Explain

Archaeology is not defined by adventure clichés but by evidence, debate, and unanswered questions. While some discoveries, such as the tomb of Tutankhamun or the Rosetta Stone, transformed historians’ understanding of the ancient world, others continue to resist explanation. Major sites and artifacts remain only partially understood despite decades of excavation, analysis, and new technology. The location of Cleopatra’s tomb has never been confirmed, and the true purpose of Stonehenge is still debated. These unresolved discoveries highlight the limits of current knowledge and explain why certain archaeological finds continue to attract global attention long after they were unearthed.

Stonehenge

Located on Salisbury Plain, about 88 miles southwest of London, is one of the most famous landmarks on Earth. Composed of seemingly ordinary megalithic stones, Stonehenge is arguably the most architecturally sophisticated prehistoric stone circle on Earth. It has piqued the interest of historians, archaeologists, and the general public for ages. Unwilling to believe that Stonehenge could be the work of human beings in an age that lacked meaningful technological sophistication, some have hypothesized that this archaeological marvel was the work of aliens. Today, one of Stonehenge’s unresolved questions is the purpose for which it was built. Was it a healing center, as some theories have proposed? A religious site or an expression of the authority of the ruling chieftains? The jury has long been out.

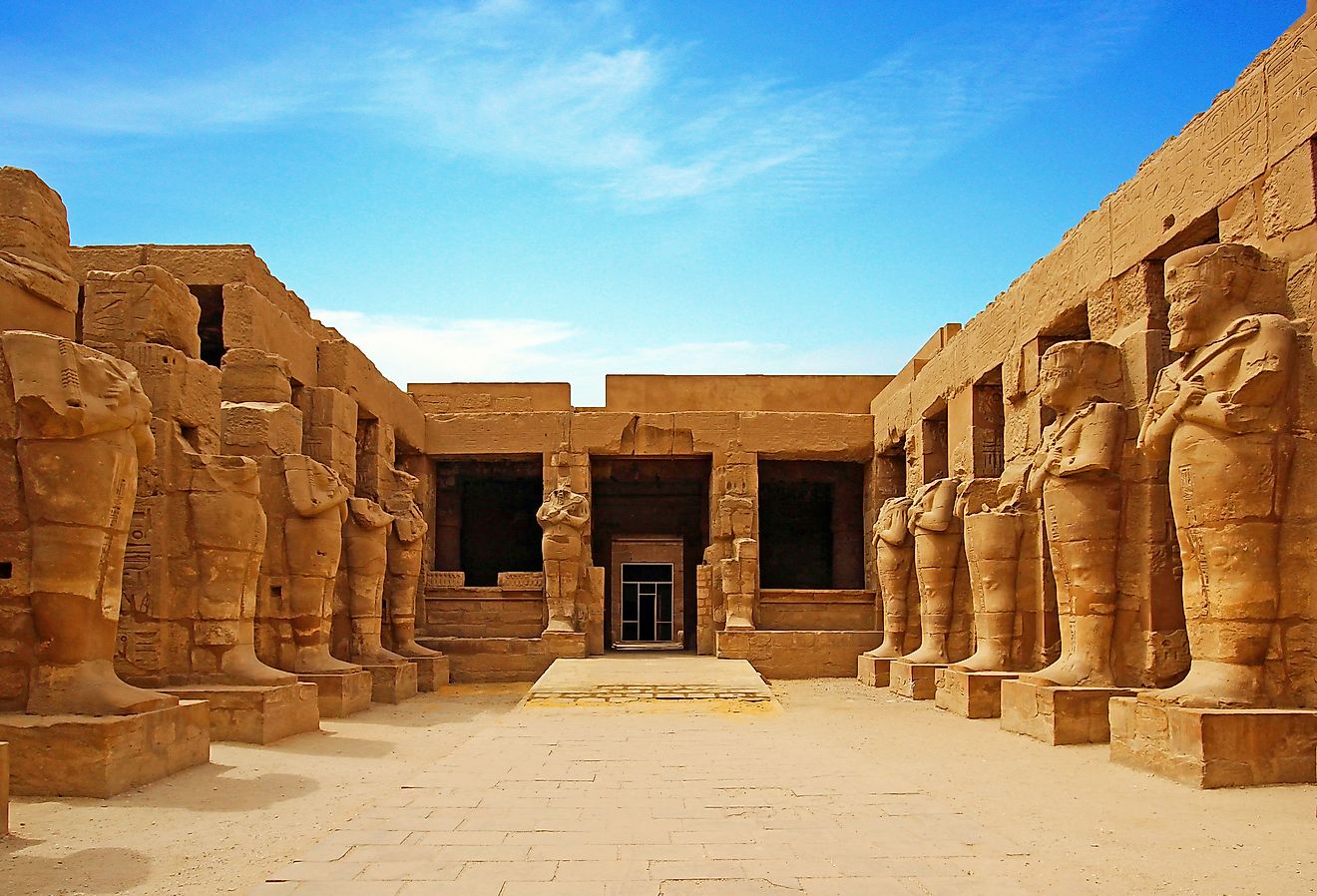

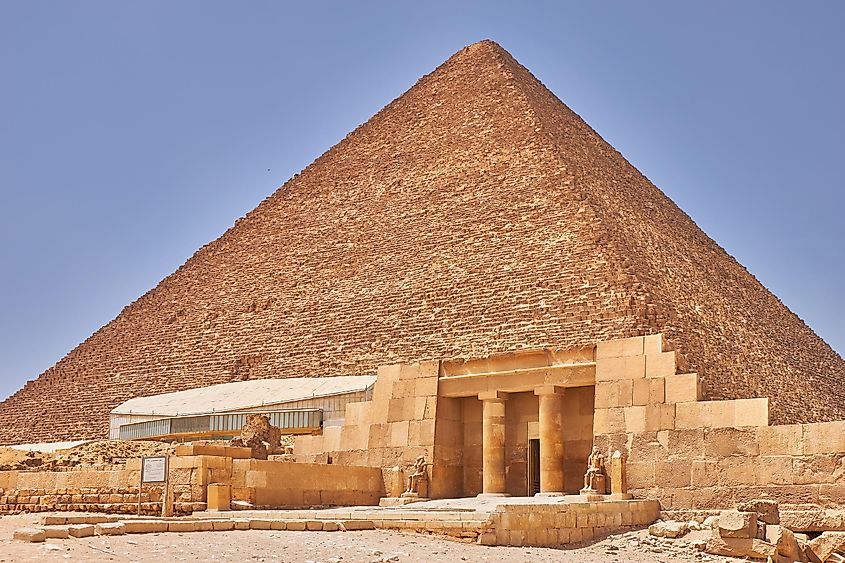

The Pyramids of Egypt

Considered by many the cradle of Western Civilization, and the intellectual fountainhead of Greece and Rome, Egypt has not ceased to fascinate mankind. Whether it is Herodotus, who wrote that Egyptians “drink from cups of bronze…wear garments of linen always newly washed” and prefer to be “clean rather than comely,” — Caeser Augustus, who relocated Egyptian obelisks to Rome after the consequential Battle of Actium, or Napoleon Bonaparte, who sent scholars to Egypt to unravel its fascinating antiquities, Egypt is an archaeological and historical treasure trove that has no peer. Yet Egypt is more associated with the pyramids than perhaps even the Nile—or any other thing. Constructed using more than 2,300,000 blocks weighing an average of 2.5 tonnes, archaeologists and historians are still scratching their heads regarding how the pyramids were built.

Gobekli Tepe

How did civilizations and cultures originate, develop, and expand? Which came first: a central place of worship, physical settlements, or farms? Traditionally, it has been widely accepted that humans first established settlements, then began farming, and eventually built places of worship such as temples or shrines. However, discoveries at Gobekli Tepe, a Neolithic archaeological site in southeastern Turkey, challenge that long-held belief. Recognized as the world's oldest temple and predating Stonehenge by around six thousand years, Gobekli Tepe’s extensive hunting-related artifacts suggest its builders may have been hunters. In many ways, Gobekli Tepe remains an intriguing mystery, highlighting the potential significance of worship sites in early civilizations.

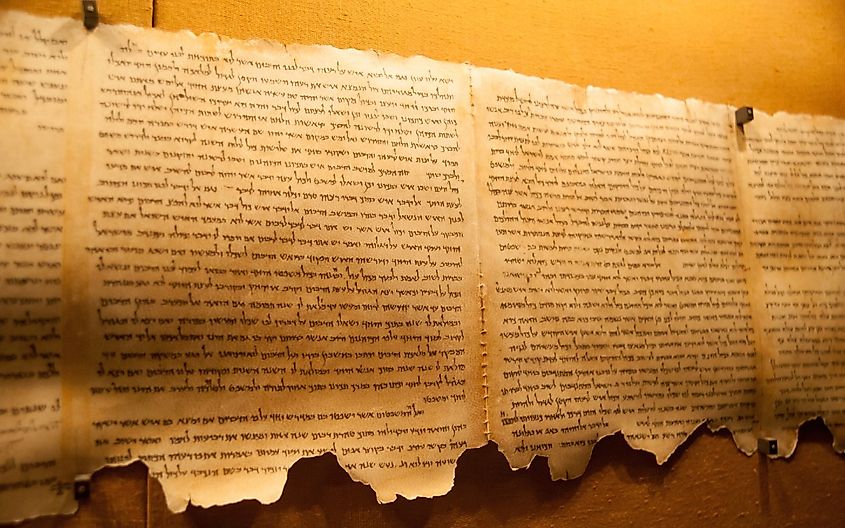

The Copper Scroll

Looking for their missing sheep, two Bedouin shepherds threw a stone into a cave, hoping that some of their flock might be trapped inside. In 1947, instead of sheep sounds, they heard the crash of broken pottery. Curious, they investigated what the stone had struck, discovering several clay jars containing old, browned scrolls. These became known as the Dead Sea Scrolls and are regarded as the most significant archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. One jar, however, held copper scrolls instead of leather or parchment scrolls. The inscriptions on the copper scrolls spoke of a hidden treasure of gold and silver worth nearly $3 billion, scattered across various parts of Israel. To this day, the exact locations of this immense treasure remain unknown, and the language used in the Copper Scroll—an ancient form of Hebrew eight centuries older than the scroll itself—remains as mysterious as the locations it references.

Pharaoh Tut

Officially known as Tutankhamun, Pharaoh Tut is the most renowned pharaoh of Egypt. However, while the boy king who died around age 19 is celebrated, his reign itself was not particularly remarkable. His contemporary fame stems from the extraordinary discoveries made by British archaeologist Howard Carter. This discovery was significant because it remains the best-preserved tomb ever found in the Valley of Kings. The world was captivated as Carter unveiled fascinating insights into how the ancient Egyptians buried their monarchs. Nonetheless, not all questions about the boy king and his tomb have been answered. For example, archaeologists have yet to determine the cause of Tut's death at such a young age. Additionally, since Tut’s tomb appears small for a pharaoh’s burial, some experts wonder whether it was truly his tomb or if it was originally meant for someone else and then repurposed for Tut.

The Hobbits

Today, the average height of an American male adult is 5 feet 9 inches. An average American female, however, stands at 5 feet 4 inches. Compare these figures to 3.5 feet, the height of humanoid fossil scientists discovered on Indonesia’s Island of Flores. Later, scientists named this unique archaeological find H.floresiensis (or Hobbits) to honor the island where they found this one-of-a-kind fossil. This could not be Homo sapiens. And because of their diminutive size, they could not also be Homo erectus. Archaeologists believed they had chanced on what could be a different human-related species. The problem, however, is the loud absence of a family tree. While several hypotheses have come forward, no theory is iron-clad.

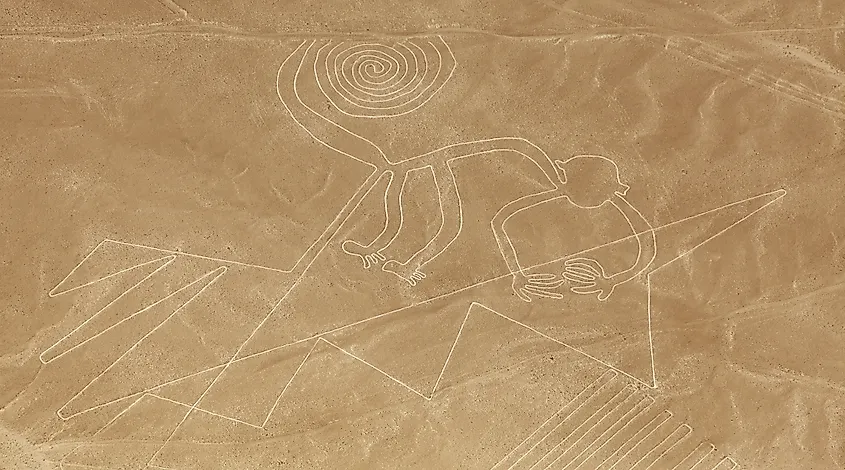

Nazca Lines

200 miles southeast of Lima, in a desiccated desert that receives less than an inch of rainfall per year, lies another archaeological mystery that still makes scientists scratch their heads. Known as the Nazca Lines, in honor of the town closest to them, these finds are a collection of unique shapes, first spotted by commercial aircraft, that continue to puzzle archaeologists. The shapes here include trapezoids, straight lines, rectangles, and swirls. When looked at closely, these shapes are outlines of animals. People have seen the outlines of a hummingbird and a monkey, among others. But some are depictions of plants. While scientists believe these are the handiwork of the pre-Inca Nazca culture, they are baffled about their purpose.

Qin Shi Huang's Tomb

Marco Polo was amazed when he traveled to China in the 13th century. He later admired China’s intricate social hierarchy and its vast wealth. The widespread use of paper money also played a role. In 1974, Chinese farmers discovered what is considered one of the most significant archaeological finds of the last century—the full-sized terracotta army of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, the founder of the Qin dynasty and China’s first emperor. Scientists have long known that this clay army was meant to guard Qin Shi Huang’s tomb. However, while archaeologists have identified the site of the tomb, they have yet to find a way to excavate it because it is surrounded by a subterranean moat filled with poisonous mercury. Will future science manage to overcome this formidable obstacle?

The Sanxingdui

"We can make our lives sublime," wrote Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, "And, departing, leave behind us — footprints on the sands of time." Yet the mystery of the Sanxingdui civilization, a culture whose curtain fell about 3,000 years ago, is that it left no footprints on the sands of time. In the year the stock market crashed in the US, setting off the worst economic downturn in the history of the industrialized world, a Chinese man repairing a sewage ditch stumbled upon a treasure trove of jade. Because of this find, archaeologists later discovered two more pits full of Bronze Age treasures, including jade. While scientists have attributed these incredible treasures to the Sanxingdui civilization, they have yet to determine why members of this ancient civilization buried so many artifacts in pits — before disappearing without a trace.

Archaeology is not for the faint of heart. It involves working long and hard—and in conditions that test the limits of human patience. Regardless, their finds are incredibly important. They shed the spotlight on ancient cultures and ancient figures we currently know little about. In other instances, however, their discoveries only give us half answers—or elicit more questions — instead of iron-clad answers. Such is the story of Stonehenge, Pharaoh Tut, and Peru’s Nazca Lines. And while these fascinating questions can be frustrating, they are often part of the excitement: The thrill in the chase.