Scientists Identify More Reliable Metrics To Protect Endangered Wild Tigers In Asia

Currently, tiger conservation successes or failures across tiger conservation landscapes in Asia are determined on the basis of changes in tiger abundance/density through periodic surveys. However, a study recently published in the journal Biological Conservation has identified more reliable and robust metrics to qualify recovery of tiger populations and achievements of tiger conservation efforts. The 13-year study (2004 to 2017) was conducted in northern India’s Rajaji National Park by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) and Panthera, the global wildcat conservation organization. It suggested that the survival rate of tigers and female tenure are more credible benchmarks for certifying long-term tiger population recovery and success.

Panthera Chief Scientist and Tiger Program Senior Director, Dr. John Goodrich, stated, “This study identifies critical metrics, right under our nose, that can help improve how we monitor tigers and ultimately implement conservation initiatives carried out on the species’ behalf across Asia.”

The Study

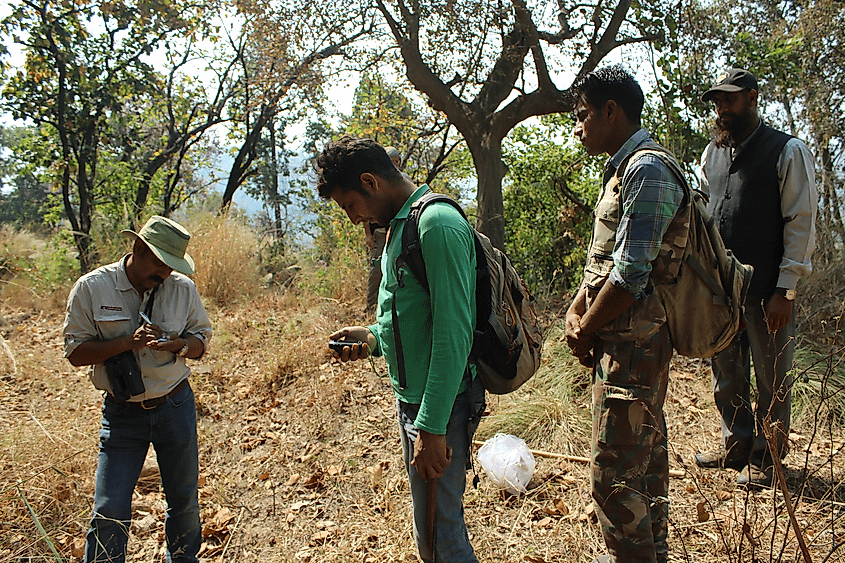

Tigers inhabiting three different habitats in Rajaji National Park were monitored for the study. The survival rate of tigers and how long females remain in a habitat and have litters were studied in the three zones.

- Zone 1: Connected to a source population of tigers in the protected Corbett Tiger Reserve. People and livestock were absent in this habitat, leading to an increase in prey like spotted deer.

- Zone 2: The second habitat was connected to the source population in Corbett Tiger Reserve and contiguous with the first one. However, it still housed families with livestock.

- Zone 3: Was not connected to tiger population in zones 1 and 2 or source. Did not have any human settlements.

The Results

- Zone 1: Tiger population density tripled to ~7 tigers/100km2 within the study period. The result was similar to estimates known from other well-protected source sites across the range. Female tigers maintained their ranges in the habitat for an average of 4 years, during which they produced 13 litters.

- Zone 2: Tiger density increased, but the survival rate was lower. Females remained for an average of only one year, with just one female producing a litter.

- Zone 3: Only two female tigers remained, making its population functionally extinct.

The Significance Of The Study

"Tiger populations across their range countries are currently being monitored using changes in abundance/density through periodic surveys. While informative, based on our study, we argue that these metrics are not adequate in many scenarios to ascertain if populations are stable, increasing or are being gradually wiped out," Dr. Abishek Harihar, Tiger Program Deputy Director for Panthera and lead scientist of the study, informed World Atlas.

"For instance, tiger numbers can show an increase in disturbed ‘sink’ habitats, particularly those adjacent to high-density source populations (zone 2 in our study), where immigration keeps compensating for the loss of individuals to poaching/conflict. But careful examination shows that individuals dispersing into such habitats usually fail to establish territory and breed. However, metrics such as annual survival and female tenure could distinguish between the protected site where females survived, established territories and bred (zone 1) and the disturbed site where a large number of surplus individuals leaving zone 1 ended up but failed to last for more than a year on average (zone 2)," Dr. Harihar explained further.

"In such cases, it is difficult to assess if conservation actions (e.g., protection, prey augmentation, compensation schemes, livelihood programs) are working well since immigration from source can continue to mask declines even if our actions fail and poaching/conflict continue. Hence, we suggest that the success of conservation efforts to secure and recover tiger populations should be evaluated using long-term demographic metrics such as survival and female tenure," he continued.

The Future Of Tiger Conservation - The Way Forward

After suffering a drastic decline in the 20th century due to indiscriminate hunting and habitat loss, wild tiger numbers are gradually rising in the present times due to concerted conservation efforts made to save the species. Today, an estimated 3,900 tigers remain in the wild with over 70% of the population confined to India.

According to Dr. Harihar, the future for tigers in Asia, in general, looks optimistic. He believes that tiger conservation has received considerable conservation attention in the recent past and will continue to do so as more range countries commit to secure populations. However, he believes that long term monitoring that assesses the health of tiger populations (and not just sizes) is critical if we understand how populations will persist across Asia.

"Currently, only about 6% of tiger range supports over 70% of known populations – known as source sites; these populations present the best hope for tiger conservation. By closely monitoring these populations' health using the metrics we propose will greatly help us understand how these sites are performing and likely contributing to repopulating the TCL’s within which they are embedded," said Dr. Harihar.

"These metrics also highlight if the conservation actions aimed to secure and recover tiger populations are having their desired impacts. We believe that the way forward is to move away from counting “all tigers” across entire countries. The focus of monitoring exercises has to be on estimating population trends and other vital parameters like survival, female tenure and reproduction. Conservation success should be measured by changes in tiger numbers, and this can be accomplished by regularly sampling select representative sites across the tiger range. Only such studies will clearly link conservation efforts to population recoveries. These can let us know if we are doing the right things for the species," he mentioned.

According to Dr. John Goodrich, the study’s findings reveal the incredible resiliency of the tiger.

"Given the right circumstances, including abundant prey, threats kept in check and connections to other tiger populations, the species can and will return from the brink," he stated.