By Hugging Trees, Communities In India Teach That Real Power Lies With The People

Scientists estimate that for the last 25 years, our planet has been losing forest land equivalent to the size of 1,000 football fields per hour! If deforestation continues at this rate, the entire world would be in serious trouble in no time. And the effects are already visible - extreme climate, vanishing of species, the spread of zoonotic diseases, the overall degradation in quality of life, and loss of ecosystem services obtained from forests. Afforestation or tree planting programs do help restore the number of trees in deforested patches, but the lost biodiversity that took millions of years to evolve can never be brought back to life. Hence, the only way to save our future is to arrest the wanton destruction of our existing forests. But how? Two movements that took place centuries apart in India prove how local communities can bring about change by unitedly protesting against activities that result in environmental degradation. Here are the two stories:

Learning A Lesson From The Bishnois Of India

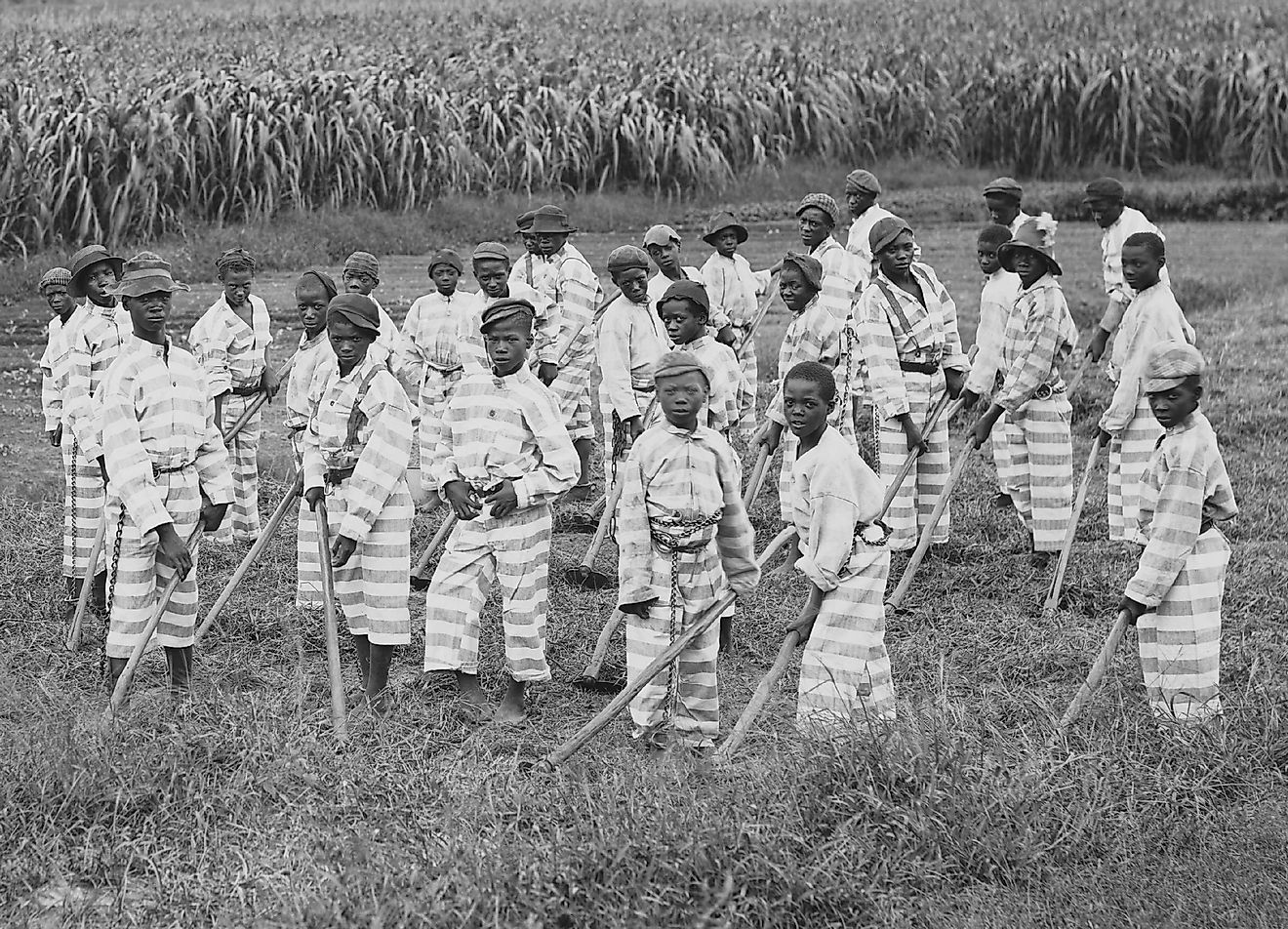

In the 18th century, India was yet to take its present shape as a country, and the land was divided into numerous kingdoms ruled by rajas and maharajas. Forests covered vast stretches of the land, and predators like tigers, lions, and leopards roamed wild and free. Deforestation was, however, still an issue at such times. But there were also people ready to lay down their lives to save a tree - the Bishnoi people of India.

The Bishnoi community traces its origin to 1542 AD when the founder of the Bishnoi sect, Guru Jammeshwarji Maharaj, laid down the 29 principles to be followed by the community. He was a man with great foresight whose teachings focussed on environmental preservation. He taught his followers to make extreme sacrifices when needed to protect animals and plants. And his followers never failed him.

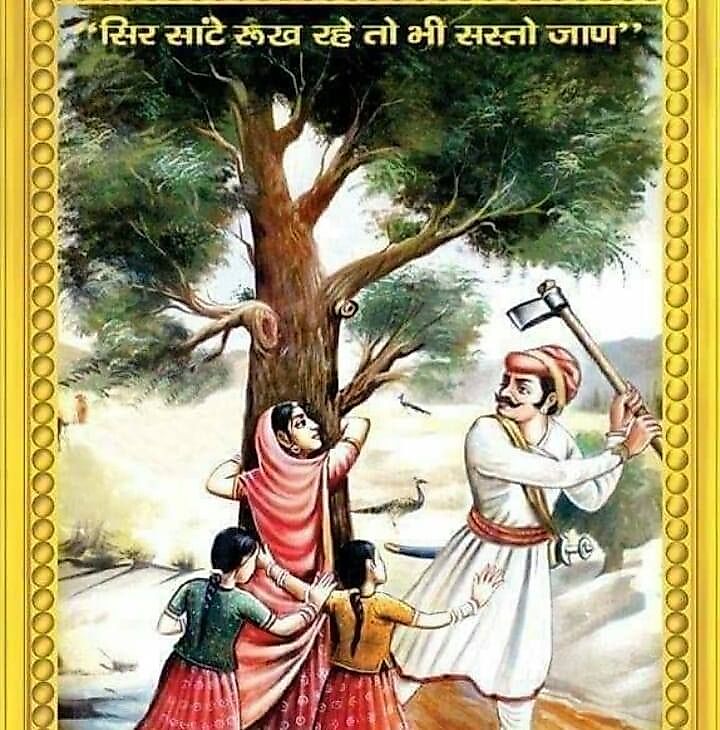

In 1787 (according to some accounts 1730), Maharaja Abhay Singh, the king of Jodhpur (Marwar) in the present-day Rajasthan state of India, ordered his men to collect wood needed to build a fort. Led by his minister Girdhar Das, the team arrived at a Bishnoi village named Khejarali where trees were found in plenty. At that time, a village woman named Amrita Beniwal was busy preparing curd in her home. On hearing the sound of the trees being axed, she came out to confront the king's men.

She begged of them to stop, but her pleas fell on deaf ears. Desperate to save the trees, she clung to them. Soon, her three brave daughters also came out in her support and followed suit. But the trees were shown no mercy, and neither were they. In an extreme act of cruelty, the king's men chopped off the trees along with the women as a punishment for not heeding the king's orders. More Bishnois from the same and surrounding villages joined the protest only to meet the same fate. 363 Bishnois including 69 women lost their lives on that fateful day trying to prevent the felling of trees. The king was not aware of the massacre as it unfolded but was deeply saddened when he received the news. He promised the Bishnois that he would never allow his men to cut green trees again.

This 18th-century event continues to inspire the Bishnois in 21st century India who fiercely protect the plants and animals living in and around their villages, towns, and cities.

"Guru Jammeshwarji Maharaj had taught us that we must plant trees whenever and wherever possible and never cut down green trees. When needed, we must also not step back from sacrificing our own lives to save a tree. He was a visionary who understood that plants are vital to our survival," said Rajbala Bishnoi, a member of the Bishnoi community in Rajasthan and a school teacher by profession.

"We believe in the principle - Sir Saante Rukh Rahe To Bhi Sasto Jaan. It means that even if we lose our life to save a single tree, we are paying only a small price for it," said Shankar Lal Bishnoi, a retired employee of the state's forest department and a Bishnoi community leader.

"A unique thing about the Bishnois is that women have always been at the forefront when leading protests and campaigns to save wildlife. Even in the 18th-century, Bishnoi women were far ahead of their times. That is truly inspiring," stated Lt. Col. (Retd.) Shakti Ranjan Banerjee, Hon. Director of the Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI)and former West Bengal State Director of WWF-India who had worked closely with the Bishnoi communities of Rajasthan to ensure the protection of wildlife in the 1980s to 90s.

The Chipko Movement - Harnessing The Power Of The Masses

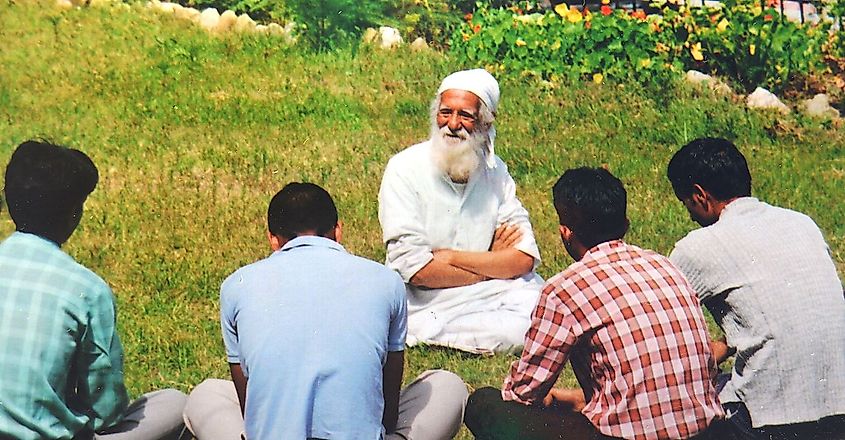

Recently, India mourned the loss of Sundarlal Bahuguna to Covid-19. Like Amrita Devi, Bahuguna is also remembered for his commitment to saving trees from being cut down. He pioneered the famous Chipko Movement (chipko means cling on to) to protect the felling of trees in the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand in India in the 1970s. The movement involved thousands of people across the Himalayan region protesting against large-scale commercial logging activities. In many cases, the people won, and the government had to yield to their demands.

It all started in 1973 when the state government of Uttarakhand planned to auction around 2,500 trees near the village of Raini. When loggers arrived in Raini to cut the trees, the local people including many women vehemently protested by hugging the trees. Their movement continued for days till the government was forced to step back. Named the Chipko Andolan, the opposition by the locals was now no longer confined to Raini. Bahuguna and Chandi Prasad Bhatt became the face of the movement and started inspiring people elsewhere in the Himalayas to adopt the same strategy to protect the trees. The successes of the Chipko Movement strengthened the resolve of local communities and soon similar protests erupted throughout the Himalayan region. In many cases, the authorities were forced to allow the people to have their way.

The above movements in 18th and 20th century India show how people at the grassroots level can prevent the disruption of ecosystems if they unite against a common threat. In both cases, the people put up a fight against those at power and yet managed to save trees from being cut down. Thus, it becomes evident that the real power lies with the people.