The Soviet Era: Ukraine's Path within the USSR

It can be hard to fathom the immense changes that happened during the 20th century. There were incredible technological advancements and huge medical discoveries. On the other hand, there were devasting conflicts that left millions dead. Ukraine and Russia experienced momentous, significant incidents in the 1920s due to World War I and the Russian Revolution.

Ukraine, historically split between empires, began to shape its national identity following the conclusion of World War I. As the sun rose on a new decade in the 1920s, most Ukrainian territories evolved into part of the Soviet Union under what came to be recognized as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

As the Soviet Union accelerated its industrial and centralization agendas, Ukraine experienced profound, and at times destructive, influences. So, Ukraine became its own country, but it existed under the control of a greater Russian power, leading to tensions in their relationship that still exist today.

Habsburg Collapse and Russian Revolution

The background of the Great War is complicated, nuanced, and a bit out of scope for this article, but as one of the most important events of the 20th century, it is important to explain. For years, tensions in Europe had been red hot. It didn’t matter if it was competing interests or long-standing rivalries, there was an atmosphere of aggression.

Occasionally in history, seemingly smaller incidents can have colossal consequences. For instance, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the successor to the Austrian-Hungarian Empire throne, was assassinated in 1914. What followed was a chain reaction that started a horrific conflict that spread over the world. A complicated network of alliances, especially among European countries, was a key factor in the conflict escalating so quickly in 1914.

In the beginning, Ukrainians were split between the empires of Russia and Austria-Hungary, making their role complicated. The Eastern Front during The Great War was a hotbed of skirmishes with the Central Powers and Russia. While the war was being waged between European countries, a different kind of war was brewing inside Russia. In 1917, the Russian Revolution started, but dissatisfaction had been brewing for a while.

Back in 1905, widespread strikes and protests had surged against Tsar Nicholas II's rule scattered throughout the nation. When January was on the horizon, peaceful demonstrators gathered at Winter Palace in St. Petersburg with the intention of presenting a petition aimed at bettering work conditions and urging political transformation. The Imperial Guard fired upon the unarmed protesters, resulting in hundreds of deaths.

The strikes ended when Nicholas II issued the October Manifesto, promising civil liberties, including the establishment of a legislative body (called the Duma), and granted fundamental rights such as freedom of speech and assembly. Despite these concessions, Russian society's underlying issues and discontent continued to simmer. Come 1917, Russia teetered on the knife edge of collapse. This was fueled by unresolved domestic pressures and further complicated as a result of its participation in World War I - which weighed heavy upon its resources and citizens.

It wasn’t just one thing. The war was making economic hardships worse. It was making food shortages worse, and it was creating discontent among both civilians and the military. In February, mass protests in Petrograd broke out, and when the Tsar's forces could not suppress the uprising, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated, ending centuries of Romanov rule. A provisional government assumed control and was immediately faced with challenges in resolving the nation's many issues. In this period of turbulence, a faction known as Bolsheviks emerged under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin. Making full use of prevailing dissatisfaction among the masses, they masterfully carried out a change in government through force in October 1917.

Key locations in Petrograd were seized, the interim administration was dismantled, and Soviet rule was ushered in, setting the stage for a Bolshevik-dominated Russia. After getting power, how to proceed with the Great War confronted the Bolsheviks. They pledged to end the war and go into talks with Germany, along with Austria-Hungary, aiming at peace. March 3, 1918, marked the day when the Central Powers and Soviet Russia concluded their negotiation. They agreed on the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The accord was pretty harsh for the Russians; hefty territorial concessions were to be made by the Bolshevik administration towards the Central Powers.

At the same time, severe issues were hitting the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Owing to numerous setbacks and insufficient resources, their ability to keep fighting was steadily weakened. When the Armistice was signed on November 3, Austria-Hungary ended its involvement in World War I. Pacts like The Treaty of Saint-Germain involving Austria and the Trianon Agreement for Hungary led to major losses in territory. The disintegration of the Habsburg Empire led to the formation of new nations from its old territories. The agreements focused on radically restructuring Europe's borders and dealing with the fallout from various imperial collapses subsequent to World War I.

Ukraine's Incorporation into the USSR

In 1917, as the Russian Empire crumbled, Ukrainians finally saw their chance for independence. The Central Rada was formed in Kyiv as a central body of the Ukrainian People's Republic during the disintegration of the Russian Empire. When the Central Rada was established in Kyiv, Soviet forces moved into the city, quickly ending Ukraine's hopes for autonomy. Around this time, it seemed the war was nearing its conclusion. Germany had entered Ukrainian lands and installed a puppet government, but after their surrender in October, they quickly left. The Rada in Kyiv made one last declaration of independence, but that did not last long either.

Following the Bolshevik Revolution, a civil war erupted between the Soviet Red Army and the White Army of anti-Bolshevik forces. With World War I and now the revolution, Ukraine had been the scene of untold bloody conflict. In only three years, countless battles were fought back and forth where modern-day Ukraine now stands. It continued when Kyiv was taken by the Red Army in 1919. By the summer of 1920, the White Army gained ground in Siberia and southern Russia. Yet, the Red Army successfully repelled the White Army into Crimea, and by December 1922, they officially put an end to the Russian Civil War, and their dominance was established. This marked the birth of the Soviet Union.

After they gained control, all of Russia's problems were now theirs to solve. According to Serhii Plokhy, who wrote The Lost Kingdom, the ‘Ukraine question’ was one of the most important questions facing the Soviet Union. As Ploky explains, it was a question Lenin would often think about.

In December of 1919, Lenin wrote, "It is therefore self-evident and generally recognized that only the Ukrainian workers and peasants themselves can and will decide . . . whether the Ukraine shall amalgamate with Russia, or whether she shall remain a separate and independent republic."

So, Lenin presented one view of what to do with Ukraine and other republics. He agreed with the demands of these republics to make a union of nations. The other side of the coin was represented by Joseph Stalin. He and others did not want a union. He wanted the republics to be under the direct control of Moscow. As one can imagine, republics like Ukraine were not too keen on the idea.

As the Ukraine question became a major focus for the Russians, Lenin and Stalin were not seeing eye-to-eye. Lenin still wanted there to be a Soviet Union with free republics in a greater union. To Lenin, the Russians faced a dilemma, having recently overthrown their imperial rulers. If they were to impose their own rule over other republics, it would contradict the very principles they had just fought for.

By late December 1922, Lenin’s wishes were finally agreed upon. On December 30, 1922, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, along with the Russian, Belarusian, and Transcaucasian SSRs, formed the initial federative entities of the newly created Soviet Union. Although Lenin envisioned a union based on greater equality, the reality was different. In practice, while the republics had autonomy in domestic matters and the right to secede, the central authority in Moscow retained control over key areas, including foreign relations and military affairs. The Communist Party in Moscow held control over the government, military, and the secret police.

The next step of the Ukraine-Russia relationship was about to take hold.

Ukrainization

Despite their differences, Lenin and Stalin both acknowledged that no matter how hard a state might fight against it, nationalism would inevitably grow. The Soviets wanted to come up with ways to deal with it before it happened.

Even after the Soviet Union was born, the problem of nationalism remained. At the time, Ukrainians were the largest non-Russian people in the union. Before his death, Lenin thought the counter to the inevitable rise of nationalism with a Soviet-identity building program, which in theory, would convince non-Russians of their true nationhood, one of a communist in the union of nations.

In 1923, the Soviets formalized a process called indigenization in an attempt to ease tensions inside their newly multi-ethnic nation. At its base, it looked to promote non-Russians into positions of power and promote local cultures through local languages or the arts. Nowhere was this more important than in Ukraine, where the process was called “Ukrainization.”

Before Lenin died in 1924, Ukrainization had begun to make significant inroads, with increased use of the Ukrainian language in official capacities and greater representation of Ukrainians in local governance. However, the full realization of these policies and their long-term impact was still unfolding. The implementation of Ukrainization continued and expanded, with increased use of the Ukrainian language in government, education, and media.

By 1928, Stalin had secured power in the party after the ouster of some of his rivals, like Leon Trotsky and Lev Kamenev, two prominent figures of the Bolshevik Revolution, paving the way for his unchallenged leadership. For years after Lenin had died, he had maintained the status quo. Now, with this newfound grip on power, Stalin saw less reason to pander to the other republics of the Soviet Union. He started to see the Ukrainian cultural revival as a threat. In 1929, leaders of the Ukrainization process were systematically removed from power.

They made a big show of it, accusing 474 members of belonging to something called the "Union for the Liberation of Ukraine" and were accused of trying to liberate Ukraine from the Soviet Union. At the same time, Stalin started to introduce the Five-Year Plan, the collectivization of heavy industry and agriculture, which would have a devasting effect on Ukrainians.

Holodomor

90 years later, the scars of the Holodomor remain on the national consciousness of the Ukrainians. The Holodomor was a man-made famine that happened between 1932 to 1933 under Stalin's rule. The term comes from the Ukrainian words meaning "death by hunger," reflecting the devastating impact of the famine on the Ukrainian population. It also helped create another divide between the Ukrainian and Russian people that has still not been bridged.

Estimates suggest that the fatalities ranged from 4 to 7 million. This leads us to wonder; what started this horror, and how did it unfold? Stalin was worried about the Ukrainian response to the forceful actions of the Soviets at the beginning of the Five-Year Plan. He was also worried about their reaction to the political crackdown on Ukrainian intellectuals and politicians during the end of the Ukrainization period. Collectivization handed control of farms and grains to the Soviets. Many Ukrainians opposed these actions as they were forced to give up land and property. After that, they would be forced to work on government-run farms.

Well-off farmers called "kulaks’" were one of the groups the Soviets fiercely targeted. According to a summary of the Holodomor by the University of Minnesota, kulaks were "declared enemies of the state, to be eliminated as a class." It was considered a vital part of the process since they owned farms and production the government wanted. By 1932 these government actions had decimated people in all of the Soviet Union, but especially Ukraine.

Hungry and famine were rampant. In August of 1932, a law was passed called the "Five Stalks of Grain." It said that any person caught taking any food or grains from a field would be either killed or sent to prison. It kept getting worse. In 1932, the Soviet Politburo forbade entire communities from leaving their towns to get food. It got so bad that many villages had troops surrounding the area to make sure no one left, effectively signing the villagers’ death warrants.

As people starved and started to die, the situation got more desperate. Reports of people eating cats, dogs, grass, and even other people were not uncommon. People were starving, dying, and decaying, but no aid was coming. Export requirements were being increased. And still, no aid from the Soviets was coming.

The immense number of deaths formed enduring imprints on the country's shared recollections. The starvation event is broadly acknowledged as a calculated act of extermination targeted at Ukrainians, designed to quash their national identity and opposition to Soviet control.

Lately, in 2018, the US Commission on Famine in Ukraine stated, "Stalin and his entourage committed genocide against Ukrainians in 1932-33." Outside the sheer immeasurable amount of human suffering, a wound was opened in the Ukrainian consciousness, an avoidable wound that has never healed. The relationship between Ukraine and Russia would never be the same as long as that unhealable wound remained.

World War II

It is almost unbelievable to consider the bloodshed seen in Ukraine and Russia in the 20th century. First, World War I and the Russian Revolution. Then, the brutal collectivism that led to the Holodomor. Next came the horrors of World War II. Like World War I, the massive and complex nature of the war is outside this article's scope, but it is still important to detail how Russia and Ukraine were affected.

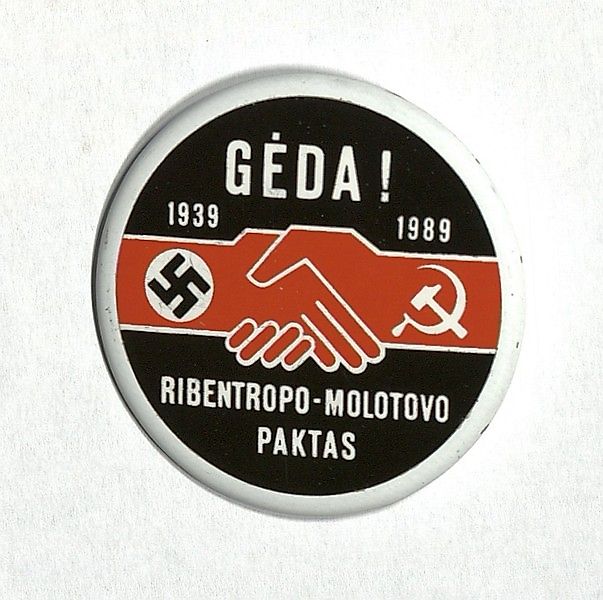

In 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany agreed in secret to a deal that would carve up Europe between the two. The deal, called the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, did not have explicit border changes but instead had spheres of influence that would fall to each nation. Barely two weeks after the pact’s approval, Poland vanished from the landscape as Germany invaded from the west and Russia came from the east. Galicia, full of Ukrainians, found itself under Soviet Union dominion. While there was some initial excitement at their liberation from the Poles, the reality was not the same as the dream. In 1940 terror and fear were imposed as sweeping arrests were made against anyone who resisted collectivism

According to David R. Maples in his book Ukraine: Stalinism in Ukraine in the 1940s, between 800,000 and a staggering 1.6 million individuals from Western Ukraine were deported; this included about 200,000 Ukrainians. The tenuous truce between Russia and Germany met its end just the next year – in 1941 when Russia was invaded by Nazi Germany. The Germans quickly advanced, and Kyiv was occupied by September.

After the horrors of the Holodomor and the reality of day-to-day life under the Stalin-led Soviets, there was some initial hopefulness. Some looked at the German soldiers as liberators. It would not take long for them to witness new horrors and new madness as the Nazis rolled through the countryside. The German occupation led to mass executions and persecution of various ethnic and social groups, particularly Jews.

One of the most well-known of these mass executions happened in a ravine of Babi Yar near Kyiv. Here the Nazis conducted a series of mass killings. Babi Yar was not only a brutal end for countless Jews but also became the execution ground for Roma people, captured Soviet soldiers, and others. This site witnessed the horrific deaths of several tens of thousands.

As the weeks and months dragged on, allegiances in Ukraine were complicated. Some Ukrainians collaborated with the Germans, some simply out of anti-Soviet sentiment. However, there existed opposition groups, such as the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), battling both Nazis and Soviet troops. With the war's momentum shifting against the Axis country, the Red Army initiated successful assaults, paving the way to free Ukrainian lands. Kyiv was re-conquered in November of 1943.

Following the end of the war in 1945, alterations happened to Ukraine's boundaries. Under prior Polish governance, the westward region was now a Soviet Union's holding. This shift meant that many Ukrainians, who had lived and been born and raised under Polish rule before the war, were now together with their fellow Ukrainians under Soviet rule.

Post-War

In the aftermath of World War II, Stalin's rule of fear and intimidation remained the same. Once again, the brutal agricultural demands of the Soviets killed scores of people. Between 1946 and 1947, famine hit the Soviet Union again, and once again, Ukrainian lands were one of the hardest hit areas. Despite pleas from the people, the Soviet government, rigid on delivery quotas, made the crisis worse by demanding more and more grains. During those two years, between 200,000 and 1,000,000 people all over the Soviet Union died because of the famine. The newly annexed Western Ukraine escaped the famine because collectivism had not been implemented yet.

Since Western Ukraine had more food, people tried to migrate to the area, but Soviet authorities attempted to halt this mass migration. They tried things like blockades and checkpoints and even arrests and deportations. During the new Five-Year Plan, the focus on heavy industry led to surpassing prewar industrial output by 1950, but agricultural recovery lagged until the 1960s.

After the war, totalitarian control was reinstated, accompanied by purges targeting perceived disloyalty. Ukrainian writers, artists, and scholars were allowed to promote patriotic themes during wartime. Now, they were accused of Ukrainian nationalism and faced persecution and repression. While Western Ukraine was initially spared the pains of collectivism, it gradually was introduced into Soviet collectivism.

The entire Soviet Union saw a giant shift after Stalin died in 1953. Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin's successor, implemented significant changes marked by de-Stalinization. This involved denouncing Stalin's cult of personality and revealing atrocities under Stalin's rule. Stalin's name was removed from public spaces, and political prisoners were rehabilitated. Khrushchev's leadership was starting to bring a moderate thaw in cultural and intellectual life, and more artistic freedoms were allowed compared to Stalin’s rule.

Some previously banned works were reintroduced. Administrative changes were introduced, such as replacing the Politburo with the Presidium of the Central Committee, aiming to reduce power concentration. The government initiated economic reforms aimed at boosting agricultural production, such as the Virgin Lands Campaign, which included a particular emphasis on increasing corn cultivation.

Russia Gives Crimea to Ukraine

In 1954, the Soviet Union decided to hand ownership of Crimea to Ukraine, changing the course of Russia's and Ukraine's history. It was more of a symbolic and administrative decision, part of Khrushchev's plan to strengthen bonds between Soviet republics and create a sense of unity. Partly it was an act of friendship to celebrate 300 years since the Pereiaslav Agreement, when Cossacks and the Russian Empire were “reunited.”

In retrospect, it might seem strange for Russia to give Ukraine this giant piece of land, but that is looking at it with a modern framework. Instead, look at it back then. At the time, it was not gifting land from one country to another. It was transferring land from one province to another. No one in the Soviet leadership could imagine that in 35 years, the entire USSR would come crumbling down.

Crimea's economic and strategic importance did not leave the Soviet Union, so at the time, it was not the momentous issue it is today. After the Soviet Union's breakup, Crimea merged with an autonomous Ukraine. This union caused serious friction and eventually led to Russia annexing Crimea in 2014.

Key Takeaways

Ukraine's turbulent journey from the Habsburg Collapse to the Soviet Union changed a lot about Ukraine and its people. The Holodomor, World War II, and Soviet rule changed Ukraine's trajectory but left lasting wounds on the national psyche. Fast-forward to current times, the aftermath looms large over the persisting conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

The passage of Crimea from Russia to Ukraine symbolized an attempted bond between friends of their union. Decades later, it has morphed into a point of contention and, gradually, war. As Ukraine and Russia grapple with their past, the Russia-Ukraine war continues to wage, a consequence of these historical choices. One action, one war, always seems to affect something else down the road.

These roots of conflict, deeply ingrained, illuminate the challenges facing the region today. Understanding this tumultuous history is essential for deciphering the complexities of war.

Works Cited:

Applebaum, Anne. Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine. Signal / Penguin Random House, 2017.

Charques, R.D. Between East and West: The Origins of Modern Russia: 862 - 1953. Pegasus Books, 1956.

Gaidar, Yegor. Collapse Of An Empire: Lessons For Modern Russia. Translated by Antonina W. Bouis, 1st ed., Brookings Institution Press, 2007.

Hosking, Geoffrey. Russian History: A Very Short Introduction. 1st ed., Oxford University Press, 2012.

Kaiser, Robert J. "Political Indigenization and Homeland-Making in Russia's Republics." University of Pittsburgh, 10 Mar. 2000, www.ucis.pitt.edu/nceeer/2000-813-18g-3-Kaiser.pdf.

Lenin, Vladimir I. "Letter to the Workers and Peasants of the Ukraine Apropos of the Victories Over Denikin." Marxists Internet Archive, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1919/dec/28.htm.

Liber, George. "Korenizatsiia: Restructuring Soviet Nationality Policy in the 1920s." Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, 1991, pp. 15-23. Taylor & Francis Online, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.1991.9993696.

Mace, James. "Ukrainization." Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 5, 1993, https://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CU%5CK%5CUkrainization.htm.

Marples, D.R. (1992). World War II and Ukraine. In: Stalinism in Ukraine in the 1940s. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230376076_3

Plokhy, Serhii. The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. 2nd ed., Basic Books, 2022.

Plokhy, Serhii. Lost Kingdom: The Question For Empire and the Making of the Russian Nation. 1st ed., Basic Books, 2017.

Reid, Anna . Borderland : A Journey Through the History of Ukraine. 2nd ed., Basic Books: Member of The Perseus Book Group, 2014.

Schlögel, Karl. Ukraine: A Nation On The Borderland. Translated by Gerrit Jackson, 2nd ed., Reaktion Books, 2022.

"Soviet Ukraine in the Postwar Period." Encyclopaedia Britannica, edited by John-Paul Himka, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/place/Ukraine/Soviet-Ukraine-in-the-postwar-period

"Ukraine in the Interwar Period." Encyclopaedia Britannica, edited by John-Paul Himka, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/place/Ukraine/Ukraine-in-the-interwar-period.

"Ukraine in the World War II (1939 – 1945)." Embassy of Ukraine to the Hellenic Republic, 8 May 2014, greece.mfa.gov.ua/en/news/22578-pres-reliz-ukrajina-u-drugij-svitovij-vijni-1939-1945-roku#:~:text=In%20general%20during%20the%20World,were%20burned%20to%20the%20ground.

University of Chicago Library. "Soviet Policy on Nationalities, 1920s-1930s." Adventures in the Soviet Imaginary: Children's Books and Graphic Art, The University of Chicago Library, https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/collex/exhibits/soviet-imaginary/socialism-nations/soviet-policy-nationalities-1920s-1930s/

Wilson, Andrew. The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation. 4th ed., Yale University Press, 2015.

Yekelchyk, Serhy. Ukraine: What Everyone Needs To Know. 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 2020.