Biodiversity Of The Carpathians

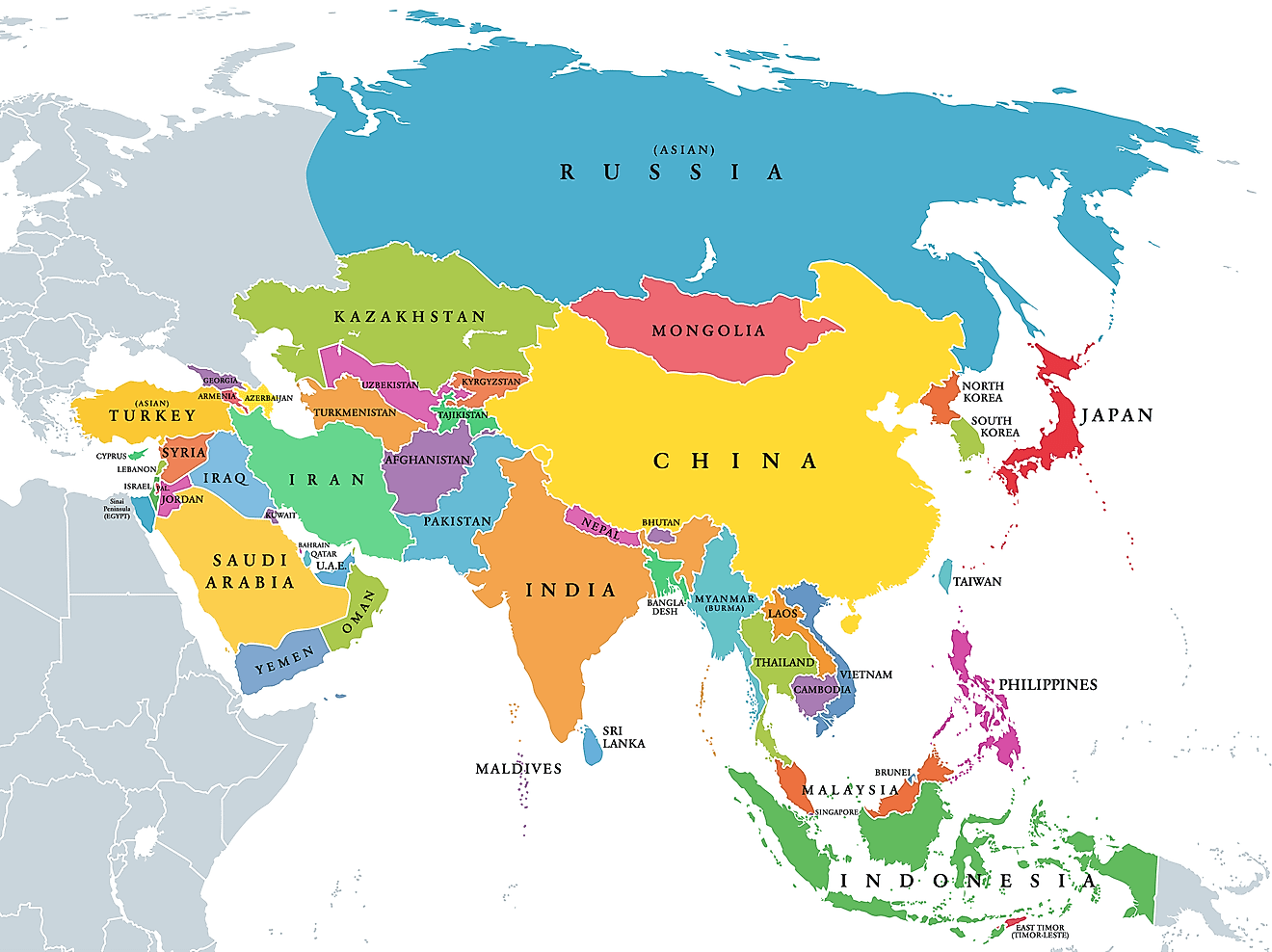

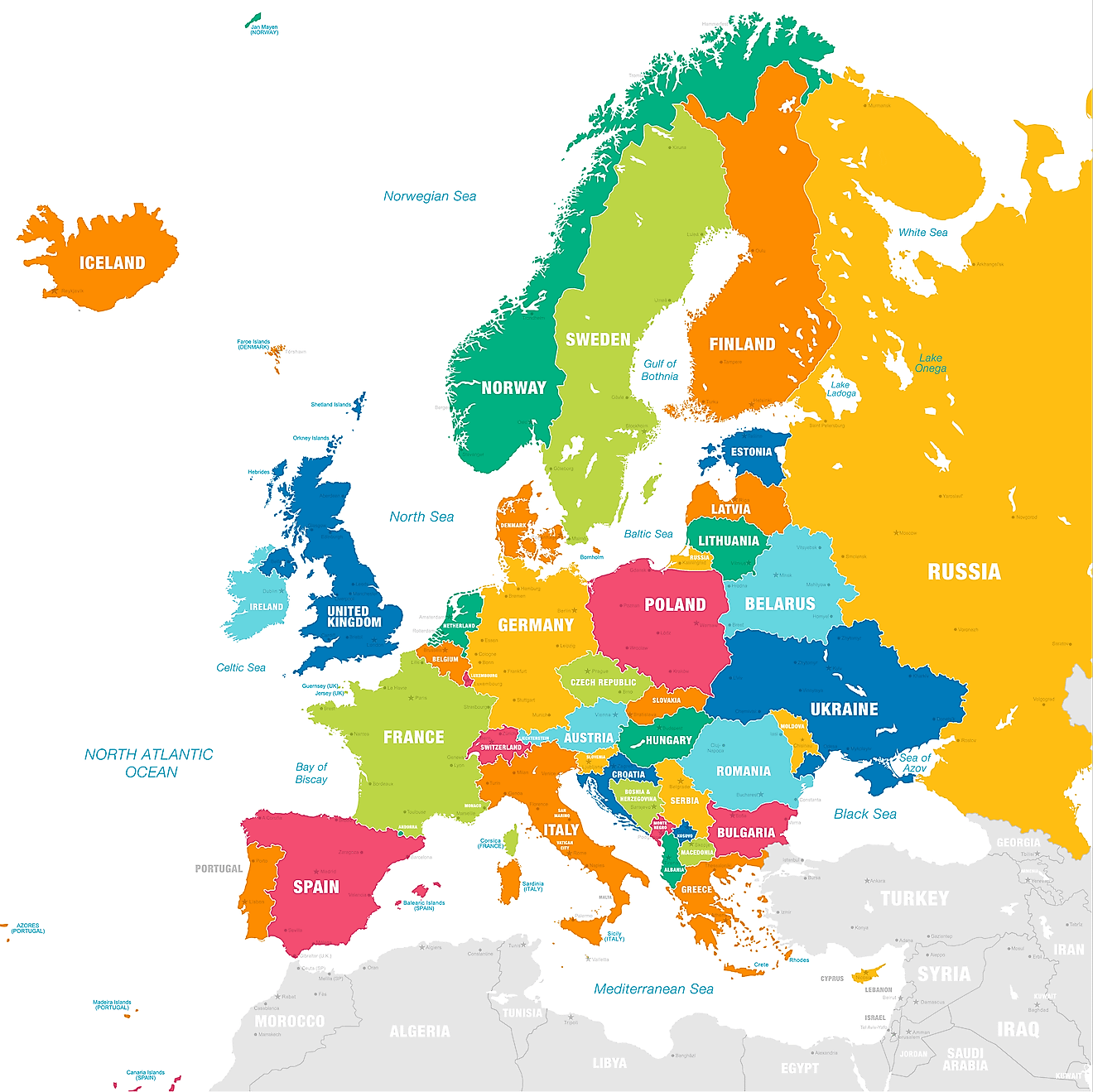

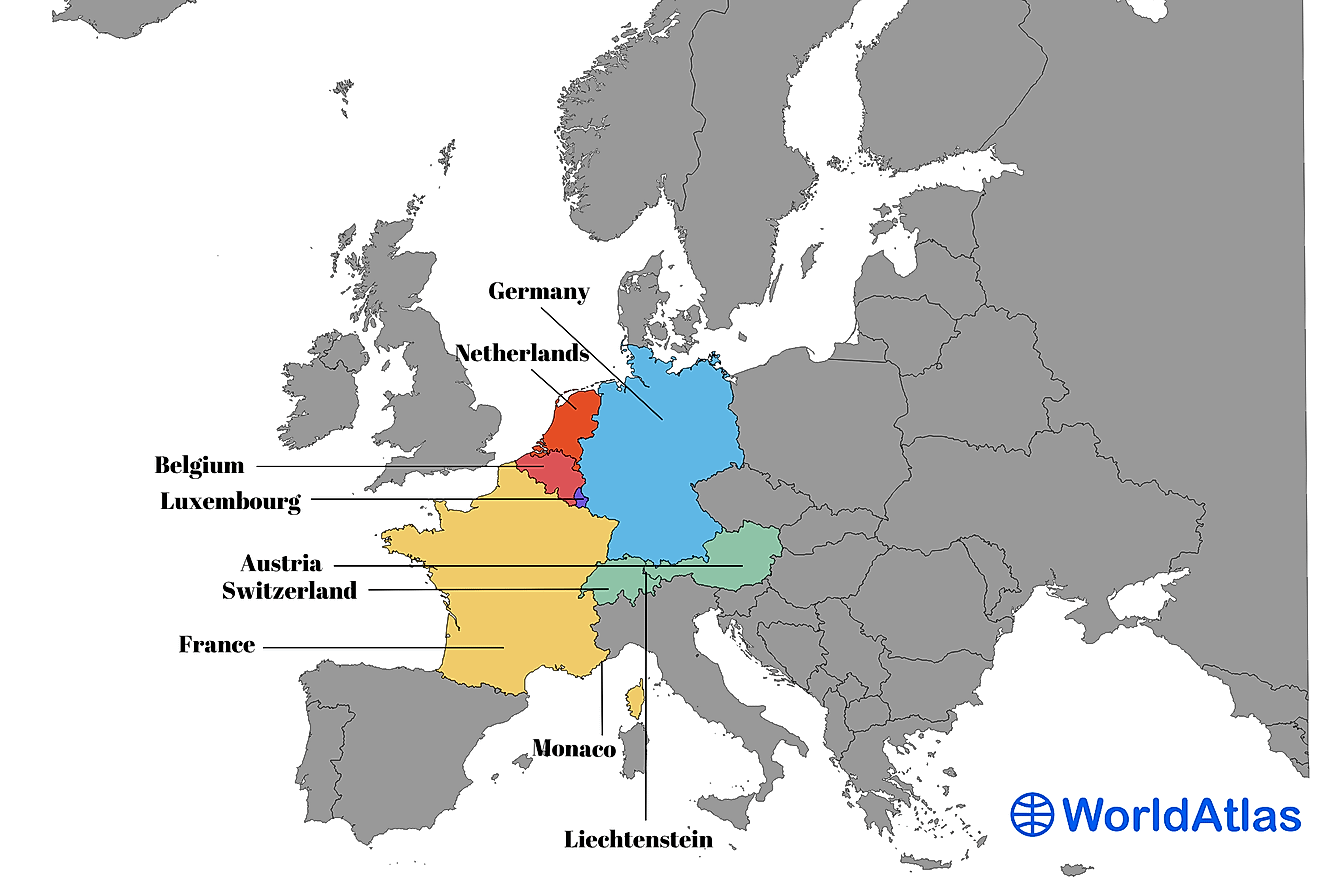

Known as the region with "exceptional levels of biodiversity, such as high species richness or endemism, or those with unusual ecological or evolutionary phenomena" (CCIBIS, June 2014), the Carpathian range is roughly 1400 km long by 100-200 km wide, spreading from the western border of the Czech Republic to the Danube river’s Iron Gate between Romania and Yugoslavia. Bordering Poland and Slovakia, the Tatras is the highest range of the Carpathians, exceeding 2,600 meters at its top peaks.

Forming an arc across Central and Eastern Europe, the Carpathians embrace the countries of Slovakia, Romania, Poland, and Ukraine, in various landscape formations and biological ecosystems. The moderately cool and humid climate supports an array of life in the Carpathians. The Carpathian Biosphere Reserve (CBR) protects nearly 64 mammals, 173 bird species, 9 reptiles, 13 amphibians, 23 fish, and over 10,000 invertebrates, as well as 64 plant and 72 animal species on the UN Red List of endangered species.

Fauna

Mammals

The Carpathians are home to the most carnivores in all of Europe, and 10 to 20 times more than in the Alps. Despite having found this paradise where they are valued and protected, over 40% of the mammals are still under threat of extinction.

Brown bears (Ursus arctors), the most widespread of the ursus, compose their largest population found in Europe, at 8,000, in the Carpathian countries. Weighing up to 400 kg, they feed on roots, insects, mammals, reptiles, and honey. They prefer to roam, feed, and procreate in large natural areas, where they their prosperity is indicative of the health of the region. Five parallel scratches on tree trunks mark their presence in the area.

It is most common to encounter a Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) during their peak hours of activity, early in the morning, or late at night, resting on the rocks and cliffs at altitudes of and above 1,000 m. They neither attack people, nor eat their livestock, but feed on hares, birds, wildcats, chamois, deer, boar, and sometimes, stray dogs. In the Carpathian countries, their population is also the densest in Europe, at 2,500 individuals.

Canis lupus or the wolf also thrives in the region, with over 4,000 individuals roaming the forests of the Carpathians, making up nearly half of its total population in Europe. With a wide distribution coverage and adaptive to various habitats, these rather shy animals are rarely encountered. The likelihood of meeting their prey in the area such as the red deer and the wild boar, indicate the health of the wolf population. Their highest density is in the Romanian Carpathians, at 3,000 individuals.

The Carpathian wisenet (Bison bonasus hungarorum) is the possible interbreeding result of the European bison with the exterminated Auroch, which was wild cattle specie. Smaller than their successors, they too went completely extinct in the 18th century.

The European bison (Bison bonasus) dates back to pre-historic times of mammoths and cave bears, when their ancestors, the great Long-horned bison roamed the lands in large groups. Since then, their numbers have been tragically dwindling, with excessive hunting activities leaving behind 30 mere populations in the world, or 1 % of their previous total. In the Polish Bieszczady Mountains, the western and eastern herds compose fewer than 300 individuals together; there is also one herd of nine in Slovakia, as well as three herds or 80 animals in Ukraine.

In December 2004, five more were introduced to the Bukovské Vrchy (Beech hills) in Slovakia, three transported from the Zoo in Prague in the following two years, and more from Germany in 2008. Extreme measures of conservation of their habitats also protect other animals that live there. Today, they can only be seen in Romania in captivity in three bison breeding reserves under National Forest Administration authority, while the protected natural parks of the Carpathians appear to be the most appropriate future habitat for their wild-roaming needs.

Other mammals inhabiting the Carpathians include the Carpathian stag (Cervus elaphus), a deer-family member that can weigh up to 300 kg, the snow vole (Chionomys nivalis) who is endemic to the rocky mountain environment, the adorable otter (Lutrinae), the curious stoat (Mustela erminea) who’s soft brown coat turns white in winter, and eight rare bat species, including the greater (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) and lesser (Rhinolophus hipposideros) horseshoes, Schreiber’s bat (Miniopterus schreibersii), and Geoffroy’s bat (Myotis emarginatus).

Birds

A heaven for birdwatchers, more than 300 different species of birds nest, migrate and winter in the Carpathians in a span of a year. One of the largest birds is the graceful black stork (Ciconia nigra) with ashen-colored back and long bright orange legs and beak. The endemic peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) can only be found on the Kuzii Massif of the CBR. Smaller mountain species include the Water pipit (Anthus spinoletta) and the Alpine accentor (Prunella collaris).

Twenty percent of the Ural owls (Strix uralensis) found in Europe occupy and thrive in the deciduous and mixed forests of the Carpathians with their numbers stable and growing at 8-10 individuals per sq. km. Preferring moist habitats, this top predator whose territory often covers 2 sq. km, feeds on other birds and animals who also detest dryer environments, such as rodents. The Tengmalm's owl (Aegolius funereus) is another common dweller of the night in the Carpathian forests.

The 200 out of the 5,000 European Golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) have chosen the Carpathians of the Central and Eastern Europe as their primary habitat and path of flight. Often sighted soaring over the ranges by avid mountain hikers, they are also a favorite subject in falconry, which is a considerable bird crime in the area. Also endangered are the fierce Lesser spotted eagle (Clanga pomarina), and the cocky-looking globally threatened Imperial eagle (Aquila heliaca).

Perhaps one of the most curious birds traversing the grasslands of the Carpathians is the concrake (crex crex), who’s bodies smoothly turn into elongated necks. Although slightly smaller and thinner than hens, concrakes bear a resemblance to poultry in the way they carry themselves, their coloring, and their distinctively rasp double-call.

The branch-hoppers include the Red–breasted Rock-thrush (Monticola), the red-winged Wall creeper (Tichodroma muraria), the delicate pale-bellied whinchat (Saxicola rubetra) of the thrush family with a distinctive white marking above its brow, and the white-chested ring ouzel (Turdus torquatus) with an air of confidence in its streamlined black body. Perhaps their opposites are the cute flycatcher (Ficedula parva), the stocky sedge warbler (Acrocephalus schoenobaenus), and the even stockier goldcrest (Regulus regulus) with humorous black and yellow mohawk on top of its head.

The woodpecker species include the spotted White-backed woodpecker (Dendrocopos leucotos), the Grey–headed woodpecker (Picus canus), the Black woodpecker (Dryocopus martius), and the Three–toed woodpecker (Picoides tridactylus).

Reptiles and Amphibians

The reptiles prefer the lower-altitude foothills of the southern regions, with semi-open vegetation which allows for an easy access to the sun and various insects to feed on. The Amphibians are more common to the moist forested regions, breeding and developing near the streams and lakes.

The spotted salamander is perhaps the most common lizard to come across when hiking over the rocky spots of the Carpathian mountain ranges. Basking in the sun, they are curious to meet people, although their backs produce a poisonous substance, which can extensively burn one’s skin, and especially the eyes.

Harbouring in the beech forests, the newt (Triturus montandoni) are protected as an endangered species of the Carpathians. The two endemic newt variations found in the region are the Carpathian newt (Triturus montandoni) and the Alpine newt (Triturus alpestris). Newts keep to themselves under stones, fallen branches and leaves on the shady slopes of the humid deciduous forests, reproducing near small water systems.

Adder (Vipera berus) comes in three variations recognized by their black, brown or grey coloring with a zigzag dorsal pattern. They spend most of their time seeking peace in the sun, or hibernating, but can be encountered suddenly in various types of terrain. Although poisonous, upon encounter, they tend to shy away from the path first. On the other hand, the long, bronzy and slick-looking Aesculapian snake, may appear dangerous, but is non-venomous.

Invertebrates

The Carpathian invertebrates, numbering at 35,000 – 40,000 different species, contribute enormously to the biodiversity of the area, with an estimated 200 unique insect species found in the small range of the Polish Carpathians alone. They are extremely sensitive to environmental changes, as seen by the dropping numbers of the 15-38mm long Rosalia longicorn (Rosalia alpine) due to deforestation of the virgin forests, in the decaying trees of which they are born and develop.

The Apollo butterfly (Parnassius Apollo) is another diminishing in numbers specie of the region, but can still found in the meadows and slopes of the Carpathians. There are ongoing efforts in the Pieniny Mountains of Poland to restore the population of this beautiful butterfly.

The endemic invertebrates of the region include the Carabus transsylvanicus and Duvalius ruthenus that can only be found on the Chornohora Massif in Ukraine. Duvalius transcarpathicus, also endemic, hide in the Uholka karst caves.

Freshwater Fish

Although not a port-bound region, fishing is extremely widespread in the Carpathians, despite lacking the abundance of fish left in the area and certain fishing laws. For the poorer households it is a means to feed the family, while recreational finishing where one can prepare their own catch is part of the Carpathian tourism. Considered a delicacy caught and prepared with love, the restaurant prices for fish can be two to three times the cost of other meats.

The fish start spawning in April and until mid-June, growing to become adults by early fall. Out of the 23 different species of fish found in the Carpathian rivers and reserves, the carp, the huchen, the madder, and the stream trout are among the top catches, while the starlet is in the Red Book of Ukraine. Other fish species include the pickerel, tench, bream, madder, perch, roach, loach, sander, bream, silver carp, as well as the larger wedge, sheat-fish, Amazonian buffalo, and pike.

Flora

With 3,988 species and subspecies in 131 families and 710 genera, the native Carpathian flora is considered among the richest in Europe, making up 30% of the continent’s 12,500 total. 383 species on top of the 99 micro species of genera Alchemilla, Rubus, Sorbus and Hieracium are endemic. Endemism of the region dates back to the species of the Atlantic, Central, Northern and Eastern European locations meeting in the Carpathians.

The largest concentrations of endemic plant species are in the Tatras, one of the most protected areas of the Carpathians. Endemic Saxifraga wahlenbergii, Delphinium oxysepalum, Dianthus, Soldanella carpatica, Festuca tatrae, Cerastium tatrae, and Dianthus praecox grow here.

With relatively little human access, the Carpathians are known for their naturally rugged environment, with many natural and semi-natural forests protected under conservation laws in the Western Carpathians through nature reserves and national parks. The rare and protected tree species include the stone pine (Pinus cembra), mountain pine (Pinus mugo), and the European yew (Taxus baccata).

The basic categorization of the Carpathian vegetation can be done by zoning depending on elevation. The foothills are bountiful with mixed deciduous forests of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur), lime (Tilia cordata) and hornbean (Carpinus betulus) in the north, and oak species such as the Quercus sessilis, Q. cerris, Q. pubescens, Q. frainetto, in the south.

The montane zone, between 600 and 1,100 m in the north and 650 to 1,450 m in the south, is almost purely dominated by beech forests, including the European beech (Fagus sylvatica) and the silver fir (Abies alba), with intermixed Norway spruce (Picea abies) and sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus). Purely coniferous forests of silver fir and Norway spruce forests are also common to certain areas.

Norway spruce forests with a small mixture of rowan (Sorbus aucuparia) dominate over the next 500 m of elevation, known as the subalpine zone. The Stone pine (Pinus cembra) feels comfortable at the highest border of the subalpine zone, also known as the alpine timberline, occurring throughout the ranges of Tatras, Czornohora, Marmures, Fagaras, Retezat.

The krummholz zone, at 1,400 m in the north-western Carpathians to 1,900 m in the south, is densely covered by mountain pine (Pinus mugo), dwarf juniper (Juniperus communis), and green alder (Alnus viridis). With the exception of the sparsely covered by alpine vegetation, high rocky peaks of the Tatras, Fagaras, Parâng, and Retezat, lush meadows spread out for the sun in the alpine zone.

The Red Book of Ukraine contains plants on the verge of extinction, such as the sparse Luzula spicata (Juncaceae) at the summit of Mt. Pip Ivan, one of the higher peaks in the Chornohora Massif at 1,990 m, in Ukraine. The most frequently traversed by hikers, the Chornohora Massif is mainly covered with fir, spruce, mixed beech and spruce forests, and topped with subalpine and alpine meadows. Other plants that grow on its slopes are the white marguerite, great yellow gentian, and the Deyl’s bluegrass in the alpine zone.

More than 400 plant species are preserved on the famous 257 ha Narcissus Valley Massif in the eastern part of the Maramureş Basin near Khust, including the rare spurred fragrant orchid, the Siberian iris, and the white cinquefoil. At the elevations of 180 to 200 m, this botanical ecosystem located on the floodplains of the Tysa River’s ancient terrace is Europe’s largest protected area, where the narrow-leaved narcissus has survived since the post-glacial period.