The World's Most Extreme Desert Climates

To many, deserts are synonymous with some of the most inhospitable climates on Earth. They’re viewed as hot, sandy, barren, and void of life. And while deserts are much more diverse and vibrant than they’re given credit for, deserts are - by definition - extremely arid and prone to temperature extremes of which humans throughout history have held onto a healthy fear.

But among those deserts, which stand out as the harshest of all? Where on earth do we see the least annual precipitation and the greatest extremes in temperature? There are dozens of arid regions on our planet, but these 4 can truthfully claim to be just a little bit drier, hotter, colder, and more difficult to survive in than most.

Atacama Desert — Chile

Outside of South America, many people associate the continent with images of the lush Amazon Rainforest or the mist-shrouded peaks of the Andes — hardly the place you’d expect to find the world’s harshest desert. But in spite of all that equatorial rain, South America also boasts extremes of the rainless variety: the Atacama Desert in Chile is the driest non-polar “true desert” on earth. Less than a single millimeter of precipitation falls on this desert every year, a dearth of precipitation unequaled by any place outside of the polar regions.

That’s because of its unusual geography. Chile is a narrow country, flanked to the west by the Pacific Ocean and Coast Range, and to the east by the Andes Mountains. Off the coast, the cold Humboldt Current doesn’t provide enough moist air for precipitation to form. And air currents play a role, too, as the region is further dried by currents of cold, dry wind blowing north from Antarctica. What moisture does remain has usually evaporated by the time it crests the Coast Range to descend into the Atacama Desert, leading to extremely low rainfall.

But that’s not the end of it. This desert is also in what’s referred to as a “rain shadow”: the Andes Mountains, bordering the desert to the east, prevent humid air from the tropical regions of South America from reaching the Atacama Desert. This perfect storm of geography ensures that some parts of the Atacama Desert have not recorded a single precipitation event since measurements began; data indicates that these patterns might date back as far as 15 million years.

The same factors that make it so dry also prevent the temperature extremes we associate with deserts from occurring in the Atacama Desert. Roughly fifteen degrees Celsius separate the average temperatures in the desert’s hottest month, December, and its coldest, July, with average monthly temperatures ranging from the mid-sixties to the low fifties Fahrenheit. When disturbances do occur, they are usually of the precipitation variety: a series of unusually abundant rainfall events in the mid to late 2010s raised environmental concerns, as life in the Atacama is well-adapted for the relative absence of water and cannot tolerate wet conditions.

Unlike less-harsh deserts, the Atacama supports very little biodiversity. While a few plant and animal species have adapted to the extreme aridity of this area, they are relatively few. Many rely on the camanchaca, an unusual marine fog that provides coastal parts of the desert with much-needed moisture. Even so, it seems only fitting that this bizarre environment is commonly used and referenced in space exploration training and research.

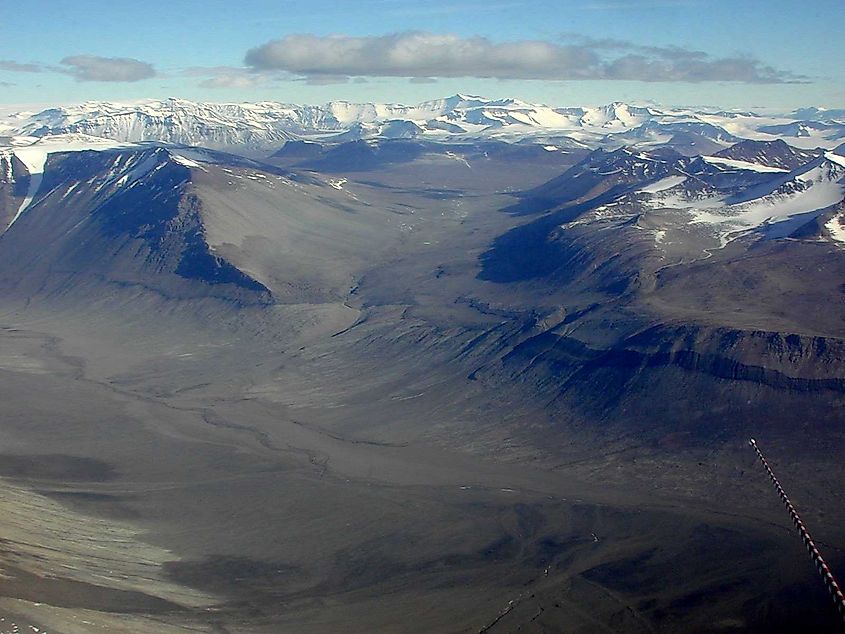

McMurdo Dry Valleys — Antarctica

Where on Earth would you expect to find a desert with near-unsurvivable temperatures, an annual average precipitation of less than six centimeters, fiercely dry winds, and some of the least hospitable conditions to life on the planet? You might put in a guess for North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, or even the Australian Outback, but you’d be dead-wrong: this is Antarctica.

The McMurdo Dry Valleys are truly as extreme as it gets. Though this is the largest expanse of ice-free land in Antarctica, the nippy annual temperature of -4° F ensures that you won’t forget you’re at the bottom of the world. In fact, the region is so inhospitable that it only began to be studied intensively in the 1990s, and scientists are still uncovering the secrets of this frozen desert as further research is carried out. So what do we know about the McMurdo Dry Valleys? Well, it helps to start with geography.

Though cold winds keep much of Antarctica extremely arid, the McMurdo Dry Valleys are located in a mountain rain shadow that amplifies those effects. The Transantarctic Mountain Range, which flanks the McMurdo Dry Valleys, blocks snowfall from reaching the valleys, and rain is rare. What snow does fall is mostly sublimated, transitioning straight from solid to gas without a liquid phase, and subsequently can’t be absorbed by the soil. Erosion and evaporation rates are startlingly low. While parts of the Atacama Desert experience less precipitation, the extreme lack of humidity in the McMurdo Dry Valleys means that many consider it to be the true driest desert on Earth.

This is not the Antarctica that March of the Penguins made famous, with its short summers and long, dark winters of fierce winds whipping up blizzards, but there is some seasonal variation to be seen in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. Summers, lasting only a few weeks, melt small amounts of glacial ice, forming temporary streams and freshwater lakes in valley bottoms. These lakes are where you’ll find the area’s microbial life.

Namib Desert — Namibia and Angola

When we picture a desert, we’re often imagining the iconic images of the Sahara that shape so many of our mental images of Africa: towering dunes traversed on camelback, or perhaps a palm-fringed oasis. But by some climatological standards, the iconic Sahara is actually not Africa’s driest desert. That title belongs to the Namib Desert, located mostly in Namibia (with parts in Angola): its driest regions receive less than 15 mm of annual precipitation. It is in some ways the prototypical sandy desert, but in others, the Namib Desert isn’t at all what one might expect.

Much like the Atacama Desert, the Namib Desert owes its aridity to the combination of air and water currents. The cold Benguela Current brings dry air to Namibia’s coast, and the region is prone to high-pressure systems that, coupled with cold ocean currents, suppress rainfall. Also, similarly to the Atacama, the Namib Desert is sustained by fog: the collision of cold seawater and warm air creates fog, which blows in off the ocean and settles over the desert.

This sea breeze also moderates temperatures in the Namib Desert, with coastal regions experiencing mild temperatures between 50° and 80° F. However, 100°-plus temperatures are sometimes recorded in areas further from the coast, or when westerly winds blow hot air across the desert. On such occasions, sandstorms can also occur, and it’s not unheard-of for the area to experience thunderstorms. The Namib Desert’s aridity is extreme, but as a general rule, its temperatures are not nearly as much so.

Far from barren, though, the hyper-arid Namib Desert is home to some of the most iconic fauna in Africa: lions, rhinoceroses, zebras, antelope, and elephants can be seen in parts of the desert, and its coasts boast abundant birdlife. Penguins are found on the southern Namib coast, and the Outer Namib is rich in smaller species. The Namib also contains six discrete plant biomes, which is part of the reason for its unusual biodiversity.

Gobi Desert — China and Mongolia

Although the Atacama Desert, Namib Desert, and McMurdo Dry Valleys are extremely different environments, they’ve had one major feature in common: a location adjacent to the seacoast. When a desert is located further inland, the lack of climate moderation by the coast often leads to the kind of temperature extremes that are popularly associated with the desert. Nowhere is that more true than in the Gobi Desert of Central Asia.

Although an annual average of under 50 millimeters of precipitation is certainly extreme, it’s the 150-degree range of average monthly temperatures in the Gobi Desert that truly makes it one of the world’s most extreme deserts. Winter temperatures on the frigid steppe can plummet to -40°, and the hottest summer months average highs of 113° F. And these extreme variations aren’t only seasonal: within a single day, temperatures can vary as much as 65° Fahrenheit.

That’s because this vast inland region of Mongolia and northern China lacks bodies of water to moderate its climate, and because winds blowing in from Siberia significantly impact the region’s temperature. As if those weren’t enough adverse weather conditions for one place, the Gobi Desert also frequently experiences sandstorms. All that amounts to a vast, rocky, high-altitude cold desert that experiences some of the most extreme temperatures of any region on the planet - an easy contender for the title of the most extreme desert climate.

The world’s most extreme desert climates aren’t only dry: some are extremely cold, others can be boiling-hot, and all are extremely dangerous to the unprepared traveler. It’s for good reason that pre-modern travelers thought of the prospect of crossing a vast desert with such trepidation, and even today, these landscapes remain some of the most inhospitable on Earth. Less than a millimeter of precipitation a year, or freezing-cold winds, baking-hot summers: for all that mankind has attempted to tame the natural world, there’s not much you can do about that. On an ever-shrinking planet, deserts stand to remind us of our place in this world.