Virginia City, A Living Ghost Town

Clinging to the eastern slopes of Mount Davidson at more than 6,000 feet, Virginia City, Nevada, rose almost overnight on a streak of silver and legend. Born of the 1859 discovery of the Comstock Lode, the first great silver strike in the United States, it became a boomtown whose fame, fortunes, and fiery setbacks still echo through its boardwalks. Today, fewer than a thousand people call it home, yet its streets, saloons, and mines feel charged with the afterimage of 25,000 souls. That tension, between bustling past and quiet present, makes Virginia City one of the West’s quintessential “living” ghost towns.

The origin story is pure frontier: prospectors Peter O’Riley and Patrick McLaughlin hit pay dirt; the name Comstock attached itself via the opportunistic Henry T. P. Comstock; and folklore credits a miner nicknamed Old Virginny Finney with christening the town after breaking a bottle at a saloon door. Whatever the precise mix of happenstance and hype, news of the strike flashed across the West and beyond. Camps and claims spread up the hillside; shafts plunged down beneath them; money and people poured in.

By 1863, the mining camp had swollen from a few thousand to well over 15,000 residents, on its way to a mid-1870s peak of roughly 25,000. Unlike many rough-and-tumble camps, Virginia City quickly acquired big-city amenities: gas and sewer lines, brick commercial blocks, the hundred-room International Hotel (with an elevator), multiple theaters and churches, and three daily newspapers. It was a full industrial city balanced, sometimes precariously, on a mountain.

Ingenuity, Wealth, and Social Fabric

That industrial leap required inventiveness. The fabulously rich but unstable ore bodies forced engineers to rethink underground work. Philip Deidesheimer’s “square-set” timbering made huge chambers safe enough to mine; Washoe pan amalgamation mills processed the ore; Cornish pumps fought groundwater; machine drills and stronger hoisting gear pushed shafts ever deeper. Even the ambitious Sutro Tunnel, draining scalding waters from the mines, spoke to a place determined to out-engineer geology itself. Conditions below ground were brutal; men snowshoed to work in winter, then descended into suffocating heat, a hardship that earned Comstock miners the grim nickname “Hot Water Plugs.”

Silver, and the gold braided through it, reshaped far more than Storey County. By the mid-1870s, Nevada supplied more than half of the nation’s precious metals. Comstock wealth buoyed the Union during the Civil War, flooded world bullion markets, and underwrote a building boom in San Francisco’s financial district via the Bank of California. Two rival power blocs came to personify the Comstock’s high drama: the “Bank Crowd,” anchored by William Sharon and William Ralston, and the Irish “Bonanza Kings”, John Mackay, James Fair, James Flood, and William O’Brien, whose Consolidated Virginia strike in 1873 became the legendary “Big Bonanza.”

The city’s social fabric was as layered as its geology. Cornish and Irish miners brought hard-rock experience and community networks; Chinese residents, about 7.6% of the population in 1870, filled essential roles as cooks, launderers, and laborers, even as they faced discrimination. Virginia City was both frontier and fashionable, equal parts saloon and salon, where Piper’s Opera House hosted touring stars while miners swapped shifts beneath their feet.

Fire and Decline

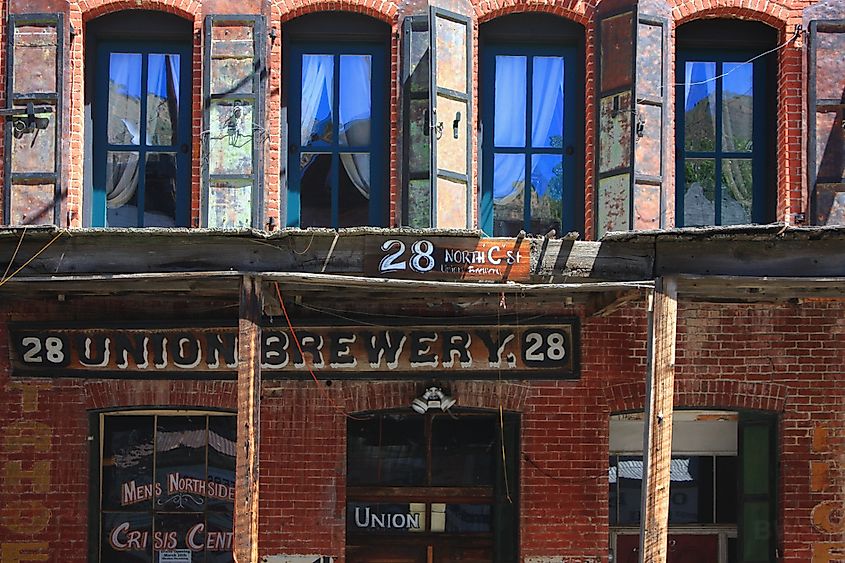

Calamity, too, left its mark. On October 26, 1875, the Great Fire roared across the hillside, reducing brick blocks “like paper boxes,” melting iron, and leaving thousands homeless. The city rebuilt with stubborn speed, but the bonanza years were already ebbing. By 1879, the richest ore bodies were fading, the mines deepened past Sutro’s relief, and the census figures began a long slide. Over the twentieth century, Virginia City dwindled from tens of thousands to hundreds.

Yet the town’s cultural imprint endured, thanks in no small part to a young reporter named Samuel Clemens. It was in Virginia City, writing for the Territorial Enterprise, that he first signed “Mark Twain” in February 1863. His Nevada sketches, later folded into Roughing It, fixed the Comstock in American letters with a mix of mischief, satire, and awe.

Living Heritage, Haunted Allure

What remains today is remarkably intact. Designated a National Historic Landmark district in 1961, Virginia City preserves long runs of false-fronted buildings and brick blocks, wooden sidewalks, and sweeping views east across the Great Basin. Museums stitch the story together: the four-story, all-wood Fourth Ward School (the last of its kind in the U.S.); the artifact-packed Way It Was Museum; the Liberty Engine Company No. 1 firehouse; and the hilltop Silver Terrace Cemetery, where elaborate Victorian monuments gaze over town. St. Mary in the Mountains Catholic Church, rebuilt after the fire, anchors the skyline as it has since the 1870s.

The mines are not just exhibits; they’re experiences. Short underground tours at the Ponderosa and Chollar mines reveal square-set timbering, ore veins, and antique machinery. Above ground, the revived Virginia & Truckee Railroad clatters past tailings and headframes on scenic excursions to neighboring Gold Hill, a moving reminder that this was once among the busiest short lines in America.

Ghosts, literal and figurative, are part of the draw. The Washoe Club & Haunted Museum and the Silver Queen Hotel, famous for its portrait dress made of silver dollars, anchor a lively paranormal circuit, from “Bats in the Belfry” night walks to quiet daylight strolls among weathered gravestones. Whether you come for chills or history, the stories are thick in the air.

Virginia City also has a taste for spectacle that would have pleased its boomtown forebears. The annual Virginia City Hillclimb sends performance cars twisting up 21 corners of the mountain grade; the International Camel & Ostrich Races and the World Championship Outhouse Races prove the local sense of humor survived the 19th century just fine; the Virginia City Grand Prix brings roaring motorcycles right down C Street. Between times, classic saloons, Bucket of Blood, Delta, Bonanza, and the Red Dog, where San Francisco rockers once cut their teeth, keep the doors swinging.

Call it a ghost town if you mean a place animated by memory. The mines have quieted; the census is small. But the past here is not past. In the creak of the plank sidewalks, the clang of a V&T bell, the glow of stained glass in St. Mary’s, and the cool hush of a timbered drift, Virginia City offers a rare thing: a chance to step back in time without leaving the world. Go softly, look closely, and you’ll hear the bonanza whisper.