Fanny Bullock Workman - Famous Explorers of the World

5. Early Life

Seemingly born with an avid interest in adventure and travel, Fanny Bullock, the youngest of three children, arrived in the world on January 8th, 1859. Her family, one firmly rooted in the early beginnings of America, was descended from early Pilgrim settlers. Fanny's parents were wealthy and considered part of Massachusetts's aristocratic class. Her father was a businessman who later would become the Governor of Massachusetts. Primarily educated by private governesses, Fanny also attended a finishing school in New York City and, after completing her term there, she traveled to Paris, France and then Dresden, Germany, and the European jaunts greatly stoked her interests in travel and adventure. Returning home in 1879, she met a wealthy, Yale-educated man named William Hunter Workman, who was 12 years her senior. Marrying in 1882, they had a daughter named Rachel the following year. Rachel, along with a brother named Siegfried (who was born in Dresden and died in 1893 of pneumonia), were largely raised by nurses and nannies while their parents were off on their many foreign adventures. Fanny's husband introduced to her mountain climbing early on in their relationship. Fanny not only quickly developed proficient climbing skills in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, but she enthusiastically took to the image of a climber, being promoted at the time as one of the 'new American women,' denoting females who were both athletically and domestically capable. Although Fanny never quite accomplished the domestic part of the equation, as she was never much of a homemaker, she was a doubtlessly a fiercely competitive athlete.

4. Career

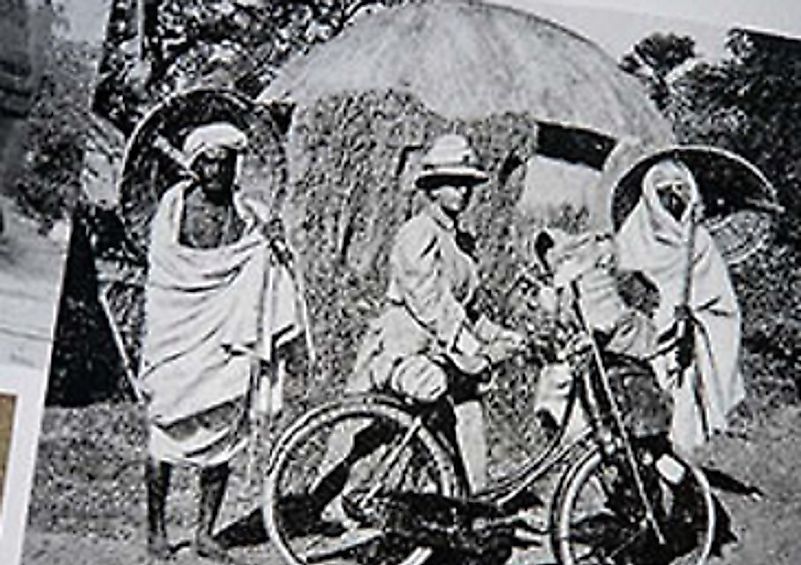

Both Fanny and her husband William seemed to have adventure flowing through their veins, and became disenchanted with the quiet and orderly style of life that they led in Worcester, Massachusetts. Longing for adventure, William retired from his job as a physician and they moved to Europe in 1889. Money to fund their adventures was not a problem, as both Fanny and William had each inherited enormous estates after the deaths of their respective fathers. Leaving their daughter Rachel and son Siegfried in the care of hired nurses and nannies, they began the adventures that kept them occupied for most of their lives. Pursuing a life beyond the dullness of domesticity seemed to be an innate ambition for Fanny, and she fashioned her unorthodox career from adventuring and subsequently writing about her adventures. In fact, the Workmans missed Rachel’s wedding in 1912 because they were exploring Karakoram Pass in the Himalayan Mountains. Their many bicycle trips took them over thousands of miles through Europe, North Africa, and the Indian subcontinent, where they traveled between 45 and 80 miles each day. Two epic trips to the Himalayas helped Fanny earn the world record for the highest climb for a female (23,263 feet on India's Pinnacle Peak), a record that remained on the books for 28 years thereafter.

3. Major Contributions

Their initial bicycle travels took the Workmans across the Alps and the countries of Switzerland, France, and Italy, and they co-wrote eight travel books along the way. In areas with more dense populations, they wrote about the people, art ,and architecture that they encountered, though the commentary regarding the remote areas turned to descriptions of sunsets and detailed geographical information. To insure their status and legitimacy in the climbing and scientific communities, Fanny and William wrote detailed scientific narratives about their mountaineering expeditions. Initially, the scientific narratives centered on the scientific equipment that they used in their climbs, however these narratives gradually evolved into providing information about the technical aspects of ‘glaciation.’ Although she was a proficient climber, Fanny discovered that her deliberately paced and naturally steady climbing pace helped her in the long run, especially in extremely high altitudes. As such, she never suffered from altitude sickness, and equated that to the slow pace and the number of overnight camps she set up to rest and recover during an extended climb, which helped her avoid altitude sickness. This approach remains to be a basic principle of high altitude climbing to this very day.

2. Challenges

Being a woman in a male dominant climbing world presented plenty of challenges. Fanny’s ambition, daring, and fiercely competitive nature, however, proved time and again to be on her side. Having to prove herself in a man’s world was not an easy task, but one she made part of each and every adventure. Indeed, in a day and age when even riding a bicycle was considered unladylike by many, Fanny was covering thousands of miles propelled by her self-generated pedal power.

1. Death and Legacy

Fanny Bullock Workman died after a prolonged bout of illness in Cannes, France in 1925. In her will, Fanny left money to four colleges, and one endowment continues, namely the Fanny Bullock Workman Traveling Fellowship. This fellowship is for a Ph.D. candidate in Architecture or Art History at Bryn Mawr College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Beyond her will, however, is the fact that Fanny left a legacy as an incredible female endurance athlete, who in her lifetime conquered more than extreme heights. The exploration and mapping of the 45-mile-long Siachen Glacier, the longest in the Karakoran Pass, is not an insignificant accomplishment. Added to that, Fanny was one of the first females to climb Mont Blanc, Jungfrau, and the Matterhorn in the European Alps. Fanny earned high honors from ten leading European geographical societies, and was one of the first in a group of women to be given a membership to the prestigious Royal Geological Society. In addition to her triumphs as a climber, she was the first American woman to lecture at the Sorbonne College in what was then the University of Paris. That she accomplished what she set out to accomplish, that is living an adventurous life, was in itself a success, and empowering to herself and future generations of women to come.