Do Spiders Sleep?

There are approximately 50,000 species of spiders crawling about this planet. They all have eight legs. Most of them have eight eyes. And many of them haunt the dreams of arachnophobes (despite being predominantly harmless and undeniably beneficial for humanity). Speaking of dreams, can invertebrates with brains the size of a poppyseed (or smaller) possibly experience such imaginary scenes? Do they even sleep in the first place? Researchers have long known about the "stupor" state that arachnids and insects enter to save energy during dormant periods. Spiders also seem to follow a circadian rhythm (i.e., an internal clock that dictates their habits). But neither of these facts quite answers the question. However, recent findings suggest that some spiders (specifically, jumping spiders) do, in fact, sleep, and strange as it sounds, they may even dream while doing so. How on earth did anyone figure this out? Let's clear away the cobwebs and get to the bottom of this issue.

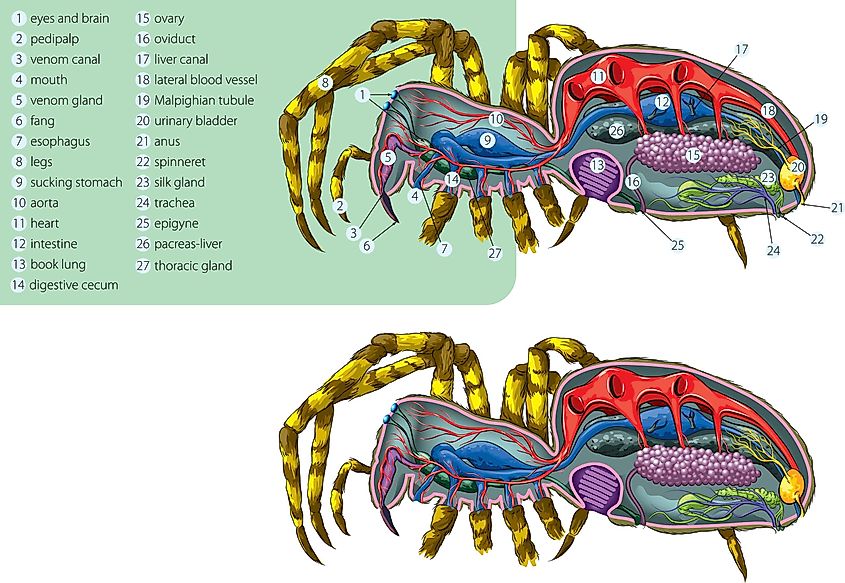

Understanding Spider Biology

Spiders are part of the class Arachnida, to which scorpions, ticks, and mites belong. They have two main body parts: an abdomen, from which the silk and spinnerets are produced, and a cephalothorax, which houses the entirety of the nervous system, and into which the legs (always eight) and fangs attach. The number of eyes does vary slightly amongst different species, but in general, spiders have eight eyes, and in all cases, they lack eyelids (the first major point of differentiation between their sleep habits and our own). Most spiders are also unable to move their eyes, either while awake or (ostensibly) while sleeping, which makes defining the rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleep (i.e., the state associated with dreaming) a little trickier.

Many spiders are nocturnal. This serves two beneficial functions. First, bugs are much more prevalent in the evening, and birds and other potential predators tend to exhibit diurnal patterns. Also, despite their many eyes, spiders don't tend to have strong vision. Therefore, the lack of light does not pose an added detriment. Instead, they rely on proprioception to sense when the prey has wandered into their web, which they spend their waking hours building and fortifying. With that said, certain species, such as jumping spiders, possess excellent eyesight and actively hunt prey during the day. In either case, spiders have a circadian rhythm regulating their active and corresponding rest periods. Spiders may rest/sleep in their webs, in a presumed same spot (such as within plants or under foliage), or, to draw on the jumping spider example once again, dangling from a silk line. Regardless of the position, it is common for spiders to tuck their legs close to their body. This helps to preserve energy and maintain warmth and may, perhaps, indicate the muscle paralysis portion of REM sleep.

The Concept of Sleep in Spiders

Sleep is defined as "a natural periodic state of rest for the mind and body, in which the eyes usually close and consciousness is completely or partially lost so that there is a decrease in bodily movement and responsiveness to external stimuli." Given the inability of spiders (and other insects) to close their eyes, and because it is so difficult to study, let alone comprehend the consciousness (or lack thereof) of such small creatures, scientists have been cautious about using the term sleep in such contexts. It is unambiguous that spiders retreat into a restful state in which their metabolic rate is lowered to conserve energy – a phenomenon known as a "stupor." The Museum of New Zealand likens this to a computer's screen-saver mode. Though seemingly powered off, the simple push of a key will immediately reawaken the machine to peak capacity. Similarly, Australian redback spiders can go as long as six months without feeding (thanks to a hibernation-like extension of the stupor state) and yet can literally leap into action when prey comes within reach. This mirrors the behavior of many other species, especially nocturnal spiders, who may sit perfectly still in their web until a trip-wire alerts them of an opportunity.

Rapid eye movement sleep, which is sometimes referred to as paradoxical sleep (i.e., a state in which the muscles are paralyzed but the brain is quite active) is well-understood in humans and has thus far been observed in many other species. Studies have demonstrated REM sleep in many mammals and birds, as well as two species of reptile, zebrafish (to a degree), cuttlefish, and octopus. However, minimal evidence has been published to support such a process amongst insects and arachnids. That is, until last year.

Research and Discoveries

While studying dozens of jumping spiders in her home, behavioral ecologist Daniela C. Rößler observed and recorded several behaviors that suggested her subjects were sleeping. In the wild, jumping spiders hunt during the day and then rest in dens or amongst dead leaves at night. Given the artificial confines arranged by the University of Konstanz researcher, they demonstrated an alternative sleeping position: hanging from the lids of the plastic boxes on silk lines.

The plot only thickened from there. After reviewing footage from her basic night-vision cameras, Rößler noted abdominal twitching and leg curling/flinching that looked uncannily similar to what we see when humans and other animals dream. But what about the rapid eye movement? As previously mentioned, most spiders are not able to move their eyes. Jumping spiders are exceptional in this regard. Long ocular tubes are able to shift their retinas. And as if gifted by the science gods, these tubes are visible during the first several days of a jumping spider's life – when its exoskeleton is translucent. Sure enough, during certain periods of the night, while otherwise hanging motionless, the ocular tubes could be seen shifting around in the spiders' heads. Though further testing is needed to determine if the spiders are less responsive to external stimuli during this unique phase, peers in the field of animal sleep have expressed excitement regarding Rößler's video evidence.

Some Ideas to Sleep On

It can be hard to relate to beings that look vastly different from us. Many animals have cute faces or demonstrate remarkable intelligence, thereby giving us points of connection and fostering a sense of responsibility to protect them. Spiders are not so lucky. Even though they keep insect populations in check and serve as a vital food source for many beloved creatures higher up the food chain, they tend to invoke aversion or outright fear. But the simple finding that spiders appear to sleep, and perhaps even dream, might inspire a gentler approach when cleaning up the attic or sweeping out the garage. More research is needed to understand invertebrate cycles and brain activity better, but where there is a will, there is always a way. Keep studying, webslinger, and you may be the one to crack the case.