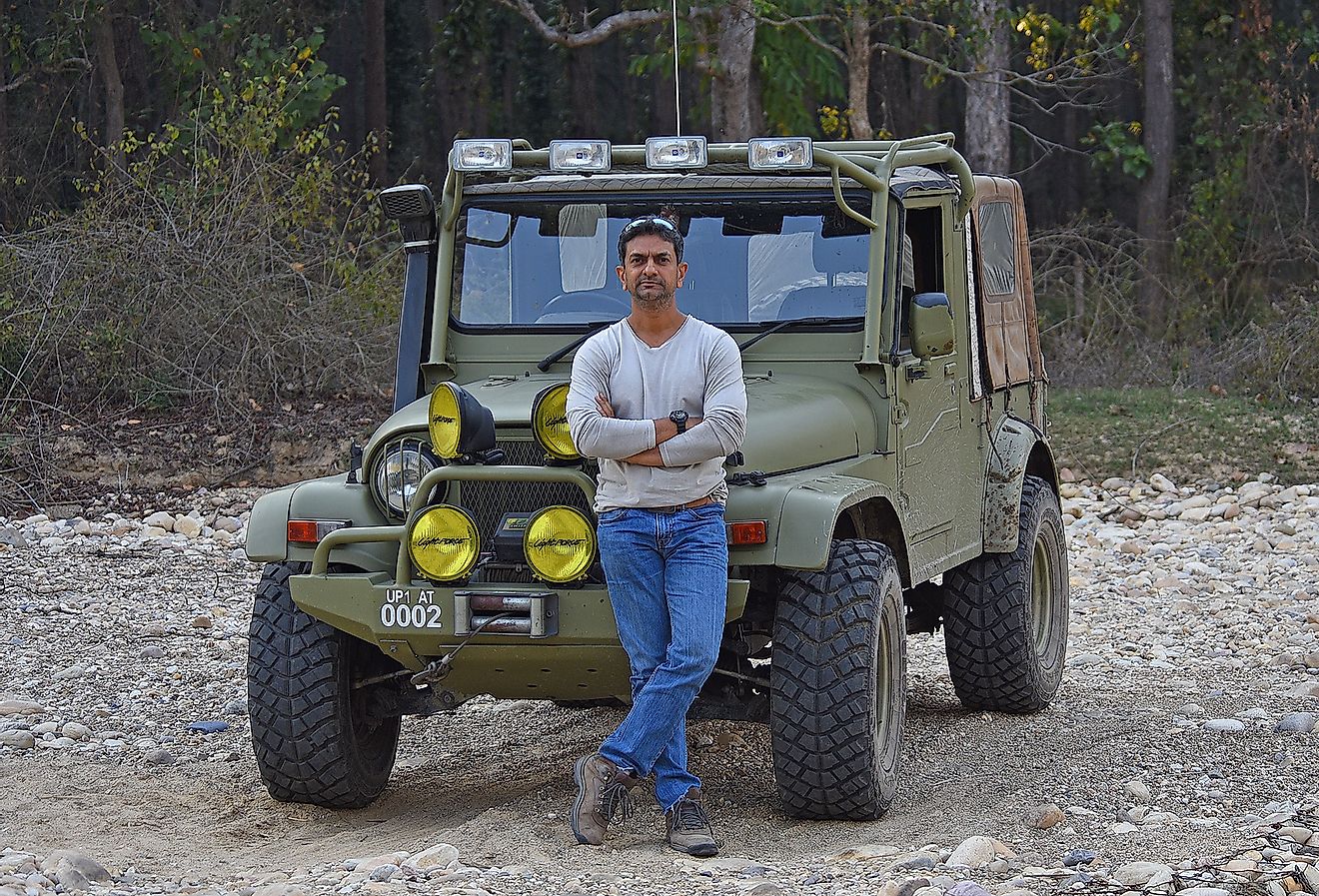

An Interview With India's Leading Wildlife Conservationist Dr. Anish Andheria

India is a land endowed with incredible biodiversity. 25% of the world's carnivore species occur in India. It is one of the world's 17 megadiverse nations. 13% of Earth's bird species, 7% of mammals, 5% of reptiles, and 4% of amphibians, are found in the country. Although India is home to an exploding population of over 1.3 billion, it has managed to conserve its biodiversity relatively well into the 21st century. Lions, tigers, elephants, rhinos, and other species that are suffering population declines in other parts of their range have stable or increasing populations in the country. India's good reputation in wildlife conservation can be accredited to the country's traditional culture and belief system and the perseverance of the wildlife conservationists working passionately for a brighter future of India's wildlife. In this article, we explore the life and work of one of India's leading conservationists, Dr. Anish Andheria. He also expresses his opinion on significant questions related to wildlife conservation and has important messages for the youth.

Dr. Andheria has many feathers to his cap. A Carl Zeiss Conservation Awardee, he is currently the President of the Wildlife Conservation Trust, one of the leading NGOs working in the field of wildlife conservation in India. He is a large carnivore biologist with field expertise in predator-prey relationships. He is also a proficient wildlife photographer. He has contributed to several national and international publications and co-authored two books on Indian wildlife. He played a focal role in establishing the Kids For Tigers initiative that has reached out to millions of school children across India, the largest of its kind in the world. He is also a member of the steering committee of two of India's state wildlife boards, and is one of India’s leading motivational speakers. He has introduced thousands of people to the joys of nature and the rationale for nature conservation.

The Making Of A Passionate Conservationist

Who or what first sparked the love for nature/wildlife in you?

Photo: An Asiatic lioness with her cubs at the Gir National Park and Sanctuary. Photo credit: Dr. Anish Andheria.

Well, now that I retrospect, I would say there was no trigger as such. My passion for the wild world was born with me and intensified with time. I would always grasp an opportunity to get up close and personal with nature. Even as a toddler, I would make every endeavor to persuade my parents to take me to the forests. Unlike today, vacationing in jungles and experiencing the thrill of wildlife safaris was quite unheard of during my childhood years. Yet, my parents ceded to my demands and took me to Gir in Gujarat to observe the Asiatic lions in their natural habitat when I was all of 5 years! At other times, the orchard behind my house served as my playground, where I would climb trees and spend long hours observing animals and birds. The Internet didn't exist yet, and unlike children today, for whom Google is their window to the world, I relied on field observations and books to enhance my knowledge of wildlife. Few places in India had libraries that served to satiate the needs of a wildlife lover. Mumbai’s Bombay Natural History Society’s (BNHS) library was one such haven. I was a routine visitor to this library, where I would spend hours reading books and research journals to have my queries on the natural world answered.

What were your earliest interactions with wild species?

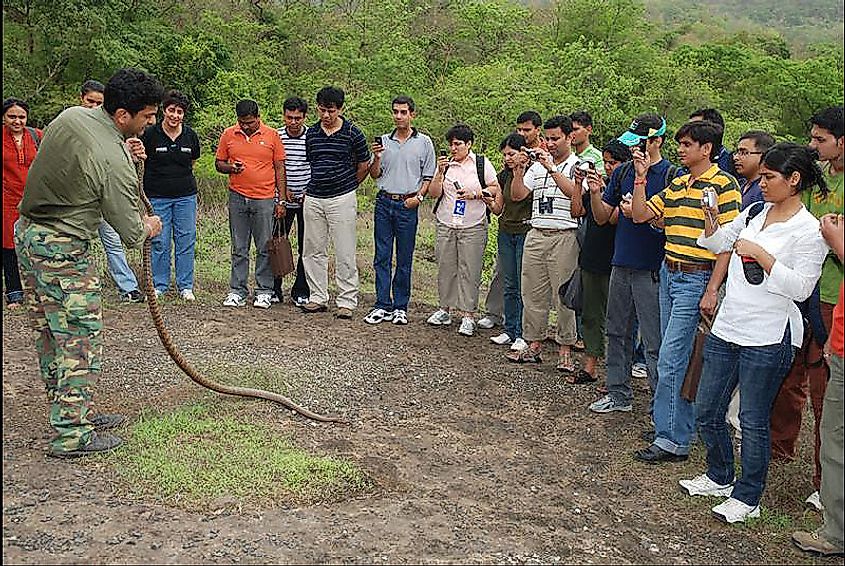

Seeing animals in trouble, always swerved me into action to save them. In my 8th standard, I rescued the first snake. It was a rat snake that was being chased by some older boys who would have clobbered it to death if I did not stop them in time. I rescued and rehabilitated many hundred snakes, several species of birds including eagles and owls, jackals, squirrels, scorpions, and also engaged in leopard rescues during my college days.

Photo: Dr. Andheria clearing the myths before releasing a rescued snake.

Even today, I continue to get rescue calls to save snakes when in Mumbai. I always believe in releasing the rescued animals in their known territory as it saves them from the trauma of adjusting to a new place.

Fortunately for me, I also had an extensive biodiverse forest, the Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP), right in the heart of my hometown Mumbai, India’s financial capital. Even the rest of the city was high on species biodiversity in the 80s and 90s. So, I developed a habit of documenting wildlife that I observed around my house and on my way to school. I would make sketches of the same and then travel to the BNHS library to identify the species.

As you explore the wild world and rescued wildlife, how did your parents respond to your interests?

Like most parents, they were quite worried. Initially, I kept my animal rescues a secret from them, but eventually, they found out about it. Knowledge about snakes was limited, and these creatures have always been associated with venom and death. Thus, despite my attempts at assuring my mother, worry never left her. Eventually, she started handling injured, non-venomous snakes to feed them water when I would be traveling. There were also times when my quest to explore the outdoors made me lose track of time. In a world without cell phones, my parents had no way of contacting me. Once, they even filed a missing person police report as they thought I was lost. However, although I was the odd one out in my family, they, especially my father, encouraged my passion by buying me books and VHS cassettes on wildlife, narrating stories of Tarzan, and in other subtle ways.

Children are often asked what they want to be when they grow up. What was your answer?

When I grew up, children were not subjected to as much pressure as the present times. Today, the world has metamorphosed into a money-churning machine. I remember that my parents never put any performance pressure on me, but I was also never getting bad marks. I would do my homework diligently before venturing out for the outdoors. My parents treated my interest in wildlife as a hobby. We hardly knew anyone pursuing wildlife conservation as a career back then. Neither were there many academic courses related to the field. I was, however, determined that I would continue to do something related to wildlife. At the same time, I knew that I did not want to be vulnerable, and hence, I always aspired for a good education.

Did your school/college help enhance your passion for wildlife?

In school, there were not too many opportunities to grow as a nature lover. However, while opting for the undergraduate course, my passion for nature guided me. I chose Bhavan's College over Mithibai, although the latter was nearer to my home because Bhavan's had a well-established Nature Club run by Prof. Dr. Parvish Pandya. So, while I continued my studies seriously in college, never missed a practical class, and even emerged as a topper, I also actively participated in the nature club events and activities, eventually becoming the director of the Bhavan’s Nature Club. I also started visiting the SGNP more frequently, often alone, on every alternate day to observe the inter-relationships between animals-animals and animals-plants. I also self-learned to track leopards in the wild during those days.

What were your favorite subjects of study? How did your education assist you in following your passion?

Mathematics, Physics, and Chemistry always interested me. I loved Biology, as well. I never looked at education as a tool to enhance my knowledge in a single subject. As a young college student, I did not have blinkers on my eyes. I believed that my textual education and degrees need not be the same as what I choose to do in the future. Education was always a tool for me to learn problem-solving and research skills, and to develop a scientific aptitude. While pursuing my Masters in Surface Chemistry, I also wrote extensively for newspapers and magazines on wildlife-related issues, never allowing a distance to develop between me and my passion.

You completed your Ph.D. degree in Surface Chemistry in 2001 from the Institute of Chemical Technology, a prestigious chemical engineering research institute located in Mumbai. Following that, instead of pursuing a conventional scientific/academic career, you joined Sanctuary Asia, a wildlife, conservation, and environment magazine in an editorial position. Why this jump in career, and how did those who knew you respond to your choice?

The choice came as natural to me even though it meant working for a salary that was initially lower than my Ph.D. stipend. I never lost sleep over wages. Those who knew me, including my parents and Ph.D. supervisor (Dr. Sunil Bhagwat), and even the Director of ICT (Prof. M. M. Sharma) were also not surprised. Although other people might view it as a career jump, I was never disconnected from wildlife. Even during my Ph.D., I learned to manage time efficiently. While doing scientific research, you learn to deal with ups and downs. When my experiments were not performing too well, instead of complaining, I would boost my morale by reading and writing articles on wildlife. My friend Bindu and I also launched a non-technical magazine called "Sparsh" in ICT that was the first one of its kind in the institute’s 60-year history. I spent over a month each year to assist in field research projects. Participation in tiger estimation programs organized by the Centre for Wildlife Studies, and led by Dr. Ullas Karanth, added to my knowledge of wildlife studies. So, when Bittu Sahgal, the founder of Sanctuary Asia, offered me an editorial position, I gladly accepted it. And… in the year (2000-2001) I joined Sanctuary we launched two of its iconic programs – The Sanctuary Wildlife Service Awards, which continue till date and the world’s most successful conservation education program in schools – Kids for Tigers.

In 2004, you took a two-year sabbatical from Sanctuary to join the first batch for the Master's program on Wildlife Biology and Conservation at the National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bengaluru. Who or what guided you into being a student again after obtaining a Ph.D.?

The course was being launched by Dr. Ullas Karanth, who was well-aware of my passion for wildlife. So, he informed me of it and advised me that it would be good if I enrolled for it to boost my knowledge in the field. He advised that having a degree in the career I was pursuing would strengthen my position in the system. I was 32 at that point of time and had already studied a lot. However, once more, my desire to make a difference propelled me to sit for the entrance exams. I cleared it with flying colors and joined the course with 14 other batch-mates who were about ten years younger than me. However, once in, I thoroughly enjoyed every moment of the two years and utilized the time to the maximum to flatter my existing knowledge of wildlife. I also published multiple research papers based on my M.Sc. dissertation.

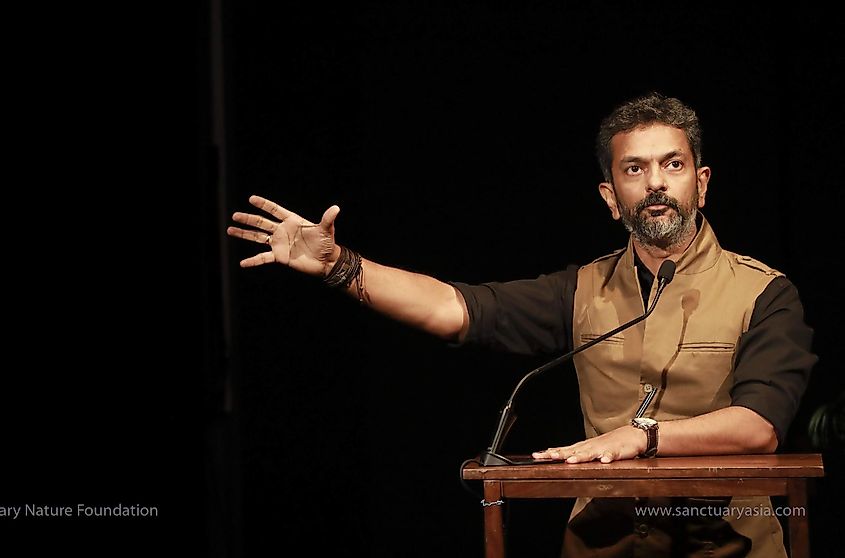

Photo: Dr. Anish Andheria. Photo credit: Sanctuary Nature Foundation

In 2009, your career took a new turn as you stepped away from the Director position in Sanctuary Asia to join Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT), today one of the most prestigious NGOs associated with wildlife conservation in India, and where you currently serve the role of the President. What drove you to adopt this new role?

As Director of Sanctuary Asia, I helped establish the Kids for Tigers program in India. At one point in time, it covered half a million children in a year. I also assisted Bittu in curating the Sanctuary Wildlife Photography Awards and Sanctuary Wildlife Service Awards aimed to recognize and reward individuals with exceptional talents and those making major contributions in saving India's wildlife.

While working with Sanctuary Asia, I came in contact with Mr. Hemendra Kothari, former President of the Bombay Stock Exchange, one of the most respected brains in the financial sector and the founder of DSP Financial Consultants Limited. Mr. Kothari had an interest in wildlife, and being a philanthropist, he wished to contribute to the field of wildlife. So, he founded the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT) that initially began as a family Trust with no office bearers. However, later a need was felt to have a team to execute the activities of the Trust to put a feedback loop in place, and I was offered the role of the Director to build such a team by Mr. Kothari. With Bittu giving the nod, I joined WCT as the first office-bearer in September 2009. Initially, I worked for both Sanctuary and WCT. Still, a year later, as WCT's operations grew, I transitioned out entirely of the former but only after finding a suitable replacement for my position. Traveling extensively became integral to my life, as I had to be in the field to monitor the work done by WCT.

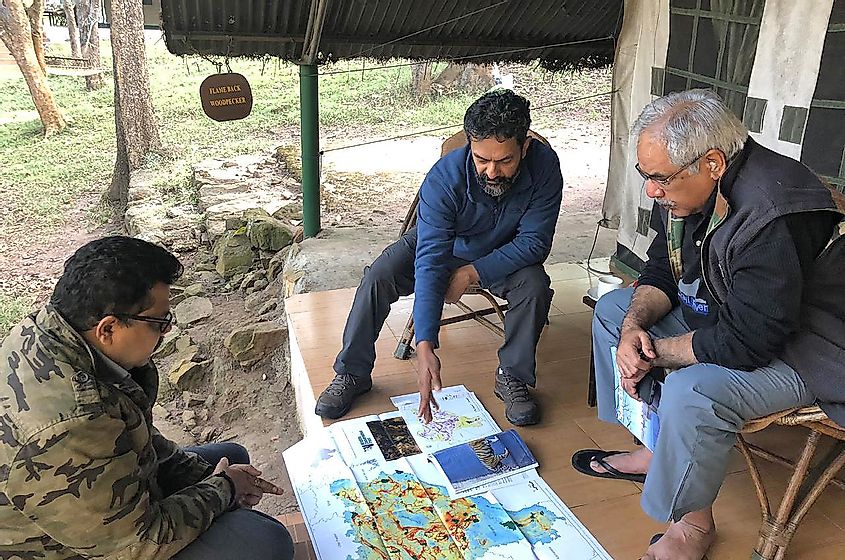

Photo: Wildlife Conservation Trust team.

A decade later, I lead a dynamic and hard-working team of 118 people and four service dogs. WCT currently has a presence in and around 160 protected areas (PAs) across 23 Indian states covering 82% of India's 50 tiger reserves and 18.5% of all PAs. WCT aims to reduce anthropogenic pressure on forests and river systems through a robust and tested 360-degree approach involving multiple stakeholders. We believe in landscape-level conservation, factoring in the needs of people dependent on these forests.

All this while, as you strived hard to build a career in your area of passion and bring about positive change in India's wildlife conservation scene, what kept you going?

Photo: WCT under the leadership of Dr. Andheria conceptualised and implemented 'Save our Tigers' one of the most successful tiger conservation campaigns. Dr. Andheria participates in an interview with NDTV, India's leading media television channel, with other leading wildlife conservationists and celebrities to discuss tiger conservation in the country.

My work is like oxygen for me. I'll be 50 in two years, and I can say that I have never done anything I did not want to do. I love how my life has shaped up. I believe I am on a perpetual holiday. Life puzzles you by presenting a billion locks before you when you are the key to only one. The probability that you find your lock in your lifetime is extremely low. But when you do realize what you are made for, you must make the most of it.

I consider success and failure as part of my journey and not as a motivator or demotivator. Putting in 100% is important, but success is not always in your favor. However, when you fail, you know why you do so and can alter action points to prevent future failures. Like a doctor cannot save every patient, even a conservationist cannot save every wild animal or forest patch. Although you feel down and out at times, you wake up every morning to a fresh start and with new hope. The thought of the young and unborn wild animals and humans for whom my generation and the past ones have left a world in lousy shape drives me to do what I do. I know that I cannot just sit and reconcile with things as it is. I learn from younger generations and derive inspiration from the successes of my team-mates. I believe in following processes captured in time and science. Even today, when I visit forests or oceans and see a wild animal, it gives me the same happiness as it did the first time I saw it. I find the wild world both fascinating and calming. Given the low level of priority given to wildlife conservation over other fields of work, people might think that conservationists are permanently engulfed in frustration. But for those who do not want to do anything else but further the cause of protection of natural ecosystems, the work is blissful.

Dr. Andheria's Messages To Conservationists Of The Future

Photo: Dr. Anish Andheria with tiger ambassadors and their teachers on a Kids for Tigers camp in 2011 at the Pench Tiger Reserve, Maharashtra.

Today, despite growth in opportunities, many young people are still subjected to parental pressure when making career choices. What is your message to all of them?

I believe that the ownership of convincing the parents lies with the children. There is always going to be a generation gap, a disparity between the expectation of parents and the roadmap the children aspire to take. Passion is highly important, but not everything. For example, although I was keen on protecting wildlife, I did not leave my studies and run away to the forest. I ensured that my grades did not go down. That way, I could do what I wanted to do, and my parents did not feel any stress. It is essential to utilize passion constructively and look comfortable in what you are doing — that way, the world accepts you.

Do you think that the education system currently prevalent in India equips the students with enough knowledge and practical experience to inspire them to pursue a career in conservation?

Currently, I don’t think the Indian education system is geared to breed environmentally conscious individuals or conservationists. Most of the people who have made a mark in the field of conservation in India are self-made individuals. Unlike other professions with set boundaries, conservation is a highly multi-sectorial field where you need to connect with experts from a variety of areas, including scientists, politicians, media personnel, communities, etc., to attain the conservation goals. A very different kind of approach is required to develop true conservationists, and that is mostly absent in the Indian education system. Also, in a country with high disparities, education in its minimal form is often not accessible to a large section of children. Most schools have a sterile atmosphere that does not encourage out of the box thinking. In conservation, you cannot have a eureka moment and claim to be a professional conservationist. A lot of passion, patience, tenacity, field knowledge, and hard work go into building a successful career in this field. Baring a couple of masters programs, one at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bengaluru, and the other at the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Dehradun, India does not have a quality specialized course in conservation.

Photo: Dr. Andheria interacting with former world Billiards Champion Geeth Sethi and World Chess Champion Vishwanathan Anand at WCT office.

What is your message to young people who wish to build a career in the field of wildlife conservation?

An individual can be attracted to different aspects of wildlife conservation. Someone might want to concentrate on saving a particular species; some others may want to protect a vulnerable ecosystem, while some may be interested in policy. Whatever be the motivation, the path to becoming a successful conservationist is similar and full of challenges. One might put in years of hard work to get a policy implemented, but a change in government can overturn things overnight. A conservationist who has spent a lifetime saving a patch of forest can lose it any day to a man-made forest fire. So, one has to be prepared for all kinds of mishaps when stepping into the field of conservation. Generally, one must do the following to prepare for a career in this field:

- Equip yourself with knowledge. Knowledge is everything.

- Learn to speak the language of science, but also be able to simplify science for the common man and policymakers.

- Prepare your body and mind for fieldwork. Stay fit.

- Interact with the natural world to become one with the ecosystem.

- Read a lot and stay abreast of the latest developments in your aspired field of activity.

- Learn to work in a team.

- Learn to step out of the comfort zone and work with individuals in a heterogeneous set-up.

- Understand legal instruments and policies.

- Be willing to collaborate with the government.

Photo: Dr. Anish Andheria and Mr. Hemendra Kothari (centre), Chairman, Wildlife Conservation Trust, signing MoU with the State Government of Maharashtra run Village Social Transformation Foundation for finding win-win solutions for rural development and conservation.

Should human welfare be taken into account while preparing oneself to conserve wildlife?

Yes. One thing that must be remembered is that conservation is different from animal welfare. The latter is often about saving an individual animal from a situation of cruelty imposed by one or more human beings. Conservation is, however, about allowing nature to be, focussing primarily on the proper management of the existing ecosystem. Conservation is mostly not about saving individuals but the species as a whole. Except for the case of captive breeding to re-introduce dwindling species into the environment, conservation deals with protecting the species in situ. To conserve a species, conservationists are often compelled to make tough choices where the individual’s wellbeing is subservient to that of the species. For example, if a tiger is responsible for multiple human deaths, and despite humans being responsible for pushing it to its limits, it might have to be put down. Its death sentence serves as a last resort to keep the humans from lashing out their anger on the other members of the species and the forest department. Thus, the welfare of humans has to be always taken into account when attempting to protect a wild species or an ecosystem to save both. Therefore, conservation cannot be delinked from humans.

How can the common person contribute to keeping the environment safe for wildlife and humans?

Photo: Dr. Andheria engaging the audience through a talk on the Use of Science in Conservation. Image credit: Sanctuary Nature Foundation.

There are multiple ways to do that, given there is a genuine urge for the same. Some of the ways include: Reduction of consumption - avoid goods that are not necessary. Change how status is perceived in society - an eco-friendly lifestyle and not material wealth should act as a determinant of appreciation in society. People in urban environments must make cautious, environment-friendly choices so that those in the rural regions aspire for the same. Volunteer with or support local NGOs to strengthen conservation work. Set up and lead groups in one’s society/locality/city to spread awareness about wildlife conservation and environment-friendly practices. Do not buy products made from wild animal body parts. Not only is it illegal, but it also puts tremendous poaching pressure on an already stressed ecosystem. Do not keep pets. Innumerable species of wild birds, reptiles, mammals, and even insects and spiders are being caught from the wild and traded across international borders to fuel the illegal wildlife trade. An exotic tortoise or a lizard that you may have bought from a local dealer, in all likelihood, was illegally caught in another country and smuggled into India.

Nature, Wildlife Conservation, And India

Photo: Dr. Andheria training the frontline forest staff of Panna Tiger Reserve, one of over 30 tiger reserves of India that received Rapid Response Units to mitigate human-wildlife conflict under the immensely successful Save Our Tigers Campaign implemented by the Wildlife Conservation Trust.

If there are three things that nature has taught you, what are they?

First and foremost, I learned that size does not matter. What we human beings consider as powerful and wealthy has no meaning in nature. Every being, ranging from a tiny ant to an elephant, has its unique and significant role in the ecosystem. When you realize that outside the human world, your role in the ecosystem is no more crucial than that of an insect, you shed away your bloated ego and learn to be humble.

Secondly, nature teaches you to live in the moment without judging the world around you. In nature, you will find other creatures living every moment like it is their last. You won’t see deer spending all their time in fear even when death lurks around them in the form of a tiger or other carnivore. They play, feed, nurse their offsprings, and lead a normal life despite the risk of becoming a meal of a carnivore at any time. In nature, every creature performs the role for which it has evolved into and does not waste time judging others.

Nature teaches you co-existence and balance, unlike human society, where the rich and the powerful win most of the time, nature works differently. Take, for example, the predator-prey relationship. It is not that the predator is the uncontested winner. There are numerous occasions when a tiger fails to catch its prey despite spending a huge amount of energy in stalking it. The tiger might even suffer injuries due to attacks by the prey. At other times, the prey is taken over by the predator and becomes a meal. So, there is no clear-cut winner but always a balancing factor that works to keep the ecosystem alive. There is nothing like ‘surplus’ in nature.

As an accomplished wildlife photographer, how do you think photography aids wildlife conservation?

For me, photography is a tool to introduce people to the amazing and uncomplicated world of wild animals with whom we share this beautiful blue planet. I am blessed to be in India, as I can shoot wildlife of all kinds without going too far out from a city. Most Indian cities still have decent biodiversity, though it has fallen drastically in the past two decades – Mumbai, Jaipur, Delhi, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Bhopal, Chennai, Guwahati, and many more big and small cities still provide excellent opportunities for photographers. I love photographing landscapes to depict a deep interconnectedness between soil, air, water, and plants. You cannot save animals, unless large, contiguous landscapes, whether terrestrial or aquatic, are saved. I also love photographing interactions between different species to communicate that you cannot save anyone species in isolation.

Photo: An osprey with its catch with an elephant in the background. Photo credit: Dr. Anish Andheria.

To save an Osprey (as seen in the above photo), which is a migratory species, you need to have a healthy river system, replete with fish. For healthy, perennial rivers, you need large, forested catchment, and these large forests can be protected in the name of large mammals such as the elephant (seen in the background). Additionally, ecosystems protected in the name of elephants, bustards, sharks, crocodiles, or tigers end up protecting a plethora of visible and hidden species of plants, animals, fungi and microbes, all of which are needed to sustain that ecosystem! Whether the audience will take to conservation by seeing images of forests, seas, and wildlife is difficult to predict; nevertheless, I believe that people save what they love and love what they see. Hence, my job as a photographer is to make people see what this planet was and is outside of what we call human society.

Wild animals are often tagged as ‘man-eaters,’ ‘dangerous,’ ‘killers,’ etc., by the media and public in general. You have extensively traveled inside the forest and often confronted wildlife during such visits. Did you ever feel threatened by wild animals?

Photo: Dr. Andheria spends a lot of time with the frontline forest staff in India's protected areas to get firsthand information on the challenges faced by them and the forests. Such ventures in the forest often bring him in contact with the wild residents of the forests like tigers, elephants, rhinos, etc.

I am a realist, and although I work for conserving wildlife, I clearly know that the forest is “their” home, and I am an outsider there. When I am going to the forest, I am obviously subjecting myself to risk in human terms. I always expect the unexpected to happen when entering a natural ecosystem, be it forest or ocean. Although there were occasions when I came close to wild species that are regarded as potentially “dangerous” like the tiger, elephant, sloth bear, gaur, or shark and sometimes the confrontations could be described as “potentially dangerous,” I always tried to learn from those situations and improve my behavior to be more in sync with wild animals.

It is a big myth that large animals and snakes are out there to kill you. The real threat is actually from the parasites in the forests like those delivered through mosquito bites that can cause deadly diseases like malaria and dengue. One thing to remember is that in nature, all animals know that ‘attack is the best defense,’ and hence if they feel threatened, they will not shy away from attacking. Even a deer can kill a human being under such circumstances. Animals can also interpret body language better than us, and a confident person might be treated differently than a nervous one by them. Since I have studied animal behavior extensively and am aware of the forest rules, I believe it was easier for me to navigate through the forest than for those who are new to the wild world. So, everyone who visits the forest must follow the rules of nature.

What makes India a unique place from the point of view of wildlife conservation?

Photo: Tiger is worshipped as 'Waghoba' in a temple in Mumbai, India.

Culturally, Indians are predisposed to conserving wildlife, and that is unique to India. Despite having a population of over 1.3 billion people, huge economic and social disparities, and religious and linguistic diversities, India has managed to conserve most of its wild species well into the 21st century. India is home to 100% of the world’s Asiatic lion population, 75% of the global tiger and Asian elephant populations, 85% of one-horned rhino populations, and more. Here, despite economic crises, people have not waged war against nature. For example, even though snakes kill about 50,000 people in India every year, mass hunting of snakes to eradicate the threat posed by them is not heard of in India, while in the US, rattlesnake hunts are not uncommon, even when deaths due to snakebites are lower by a magnitude. The Indian culture inculcates compassion in individuals for everything alive and establishes the connectedness between humans and other living beings.

Although British rule did manage to leave behind a culture of sport hunting of wild animals and their extermination, after they left, India once more sprang back to her former self that valued wildlife. The Indira Gandhi-led government played a major role in drafting laws such as the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, and the Forest Conservation Act, 1980, and implementing projects like the Project Tiger that ensured that Indian wildlife received the much-needed attention and protection. They are some of the best-drafted conservation instruments in the world.

Even today, when foreigners visit Indian forests, they are awestruck by what they witness - people living in close contact with predators and other wildlife. For example, the fact that about 40 leopards live in the heart of Mumbai city in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park and its peripheral areas, is quite an astounding phenomenon.

How do you paint the picture of Indian wildlife a decade from now? Does it look optimistic?

Photo: Dr. Andheria discussing WCT's white paper on the impact of linear infrastructure with senior forest department personnel.

The trajectory adopted by the Indian government for development will determine the future of wildlife in India. If the focus is to build thousands of kilometers of road and a profusion of seaports, develop big nuclear power plants, link one river with another, extract electricity from coal, and use other unsustainable practices to achieve developmental goals, then Indian wildlife will surely suffer great losses.

Although the Indian culture and legal system have helped conserve the country’s wildlife quite well into this century, future issues arising from growing population and consumerism might alter the entire scenario. Already, I can see the symptoms of change in Indian society. People are increasingly becoming less tolerant of wildlife. Cases of tiger electrocution, leopard poisoning, bludgeoning of bears with sticks and stones, butchering of snakes, etc., are becoming more common. It must be remembered that whenever a society is under stress, forests suffer the most. Unless we have sufficient, renewable natural resources to meet the needs of India's growing population, we cannot have a stable society. When the people starve for the need for such resources, there will be unrest within the society, and the law-abiding citizens will start taking the law in their own hands. Such an unstable society can destroy a million-year-old forest within a few days. We do not have another million years to grow it back.

So, ten years from now, India's future will depend on the path taken by the country towards development. It will primarily depend on how the country views development - in terms of physical and financial capital improvement or as maintaining and enhancing the existing natural capital.

So, how can sustainable development be ensured?

Photo: As a self-imposed rule, Dr. Andheria engages with an assortment of forums across India and abroad to improve the understanding of various constituencies about the impending stresses on forests and wildlife.

Wetlands (ponds, lakes, mangroves), grasslands, last remaining forests (arid, deciduous, evergreen, etc.), mountain ranges (the Himalayas, Western Ghats, Satpura, Aravalis, eastern ghats, etc.) must be left alone and not subjected to any environmentally unfriendly human disturbance. To sustain the burgeoning human population of India, a huge amount of natural resources (water, soil, oxygen, food, etc.) will be consumed. The provision of which is not possible in the long run if at least one-third of the country’s total area is not maintained as good quality forests. Although today, approximately 21% of India is covered by forests, only around 5% of India can be described as ‘good quality’ forest. Thus, not a single patch of the existing forest can be sacrificed in India.

The government, corporations, and industries should keep the environment as the most important indicator of measuring their success. Anything that brings profit at the expense of the environment should be phased out. The use of green technology must not be limited to posts on social media but harnessed by governments and corporations to build an energy-efficient future. Existing infrastructural networks must be improved instead of building new, fancier ones. More energy-efficient automobiles must be launched in the market. Anything that ensures a cleaner and greener future must be adopted and implemented without wasting any time. In short, this decade (2020-2030) will determine whether India becomes ecologically and hence economically stable or gets pushed towards an era of environmental and social crisis.

To know more about Dr. Anish Andheria, please visit https://www.anishandheria.com